Economic Perspectives January 2026

Read the full publication below or click here to open the PDF.

- Geopolitical tensions have escalated dramatically over the past month. As part of his pressure campaign to acquire Greenland, Donald Trump announced 10% extra tariffs on 8 European countries (going into effect on 1 February). European leaders have vowed to retaliate if the tariffs were to be implemented. Though Donald Trump has since walked back on his threat, we still see the possibility of a full-blown EU-US trade war as an important downside risk to our scenario.

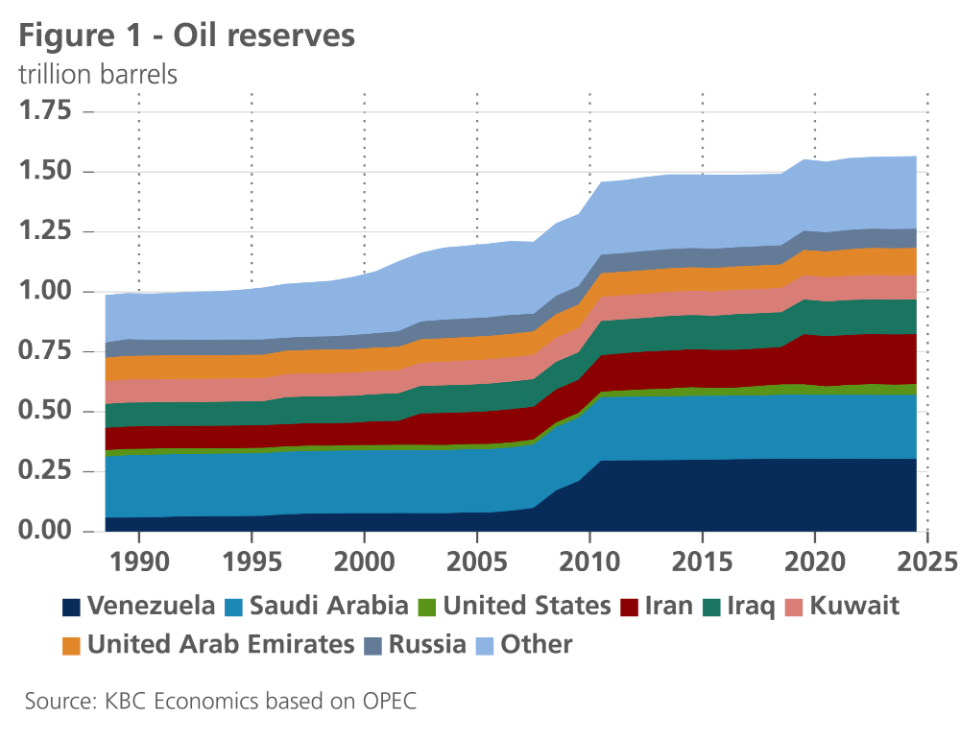

- High oil supply is continuing to push oil prices down. Prices declined 2.2% in December to 60.9 USD per barrel. Tensions in Venezuela (which supplies around 1 million barrels per day) had pushed prices upwards earlier in the month. However, futures dropped in the medium term, as markets expect US involvement to raise Venezuelan output in the years ahead. TTF gas prices remained unchanged at 28 EUR per MWh last month as high US LNG output keeps a lid on European natural gas prices.

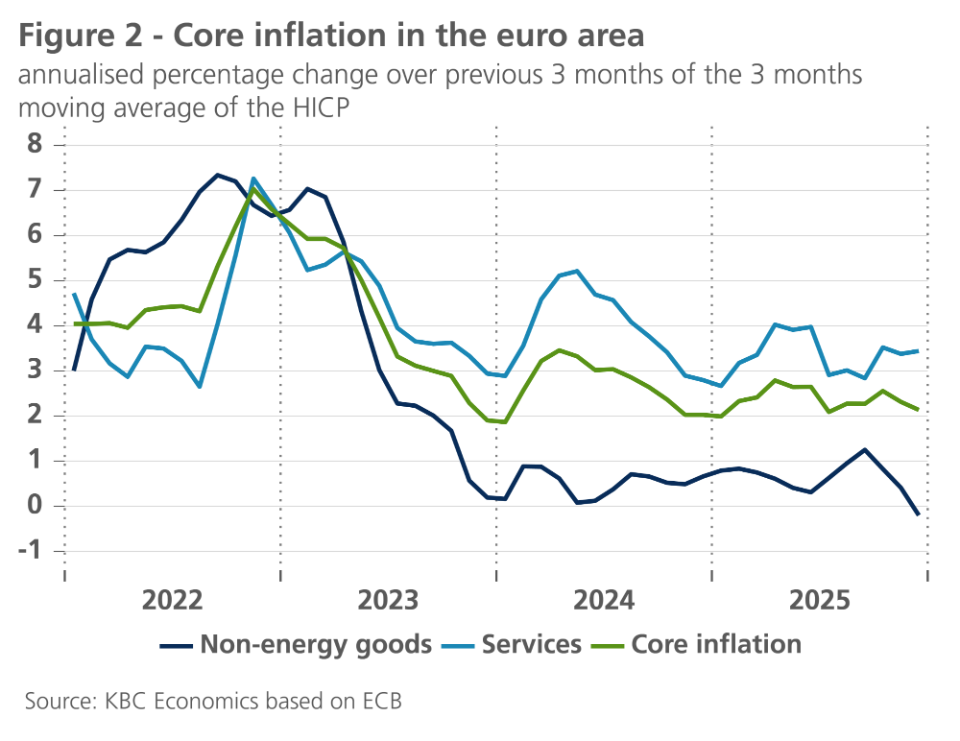

- Euro area inflation dipped below the ECB’s target in December as it declined from 2.1% to 1.9% year-on-year. Within non-core components, energy inflation showed a big drop, while food inflation firmed. Core inflation also ticked down from 2.4% to 2.3%. Within core components, goods inflation softened. However, the momentum in services inflation remains elevated and wage pressures have picked up. We now expect average inflation to be 1.7% in 2026 and 1.9% in 2027.

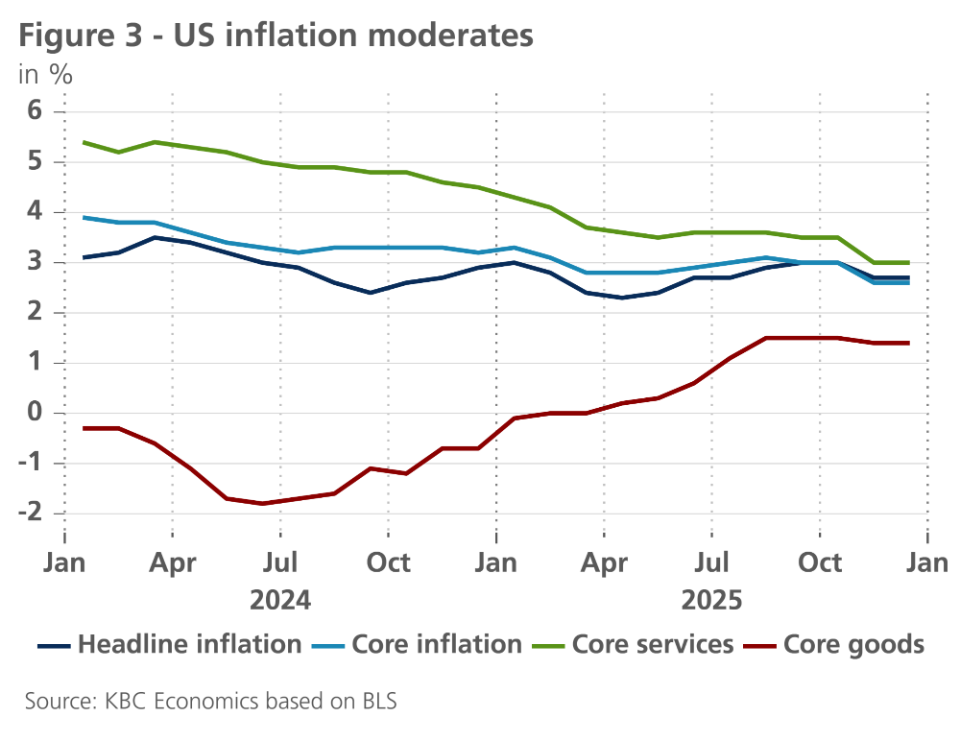

- US inflation is past its peak. In December, headline inflation remained unchanged at 2.7% year-on-year, while core inflation softened from 2.7% to 2.6%. Shelter and food inflation were elevated, while core services inflation (ex. shelter) was modest. Goods prices were unchanged, thanks to a decline in used cars and trucks prices. Other (tariff-sensitive) goods components still showed elevated increases. We now expect 2.6% and 2.4% average inflation in 2026 and 2027, respectively.

- Euro area growth remains tepid. Business sentiment weakened last month (for both manufacturing and services). Consumer confidence remains weak, explaining the historically high household savings rate. Industrial production data improved, however. A mildly stimulative fiscal stance of the euro area as a whole will provide modest support to this year’s growth figures. We forecast GDP growth to be 1.0% this year and 1.4% next year.

- The US economy remains in good shape. Q3 2025 GDP growth came in at 1.1% quarter-on-quarter, thanks to strong consumer spending. Growth is likely to be strong again in Q4, as indicated by strong retail sales and rising exports. Job growth remains weak, but productivity is rising at a rapid pace, and the unemployment rate remains under control. Given overhang effects from the strong Q3 and Q4 figures, we now expect 2.3% GDP growth in 2026. We forecast growth to be 1.9% in 2027.

- Chinese real GDP grew 5% in 2025, meeting both the official government growth target and the growth rate of 2024. Resilient exports supported the economy against lackluster domestic demand and recently weaker investment. We therefore expect the longer-term structural slowdown in the economy to continue in 2026 and 2027, with real GDP growth of 4.6% and 4.2%, respectively.

- Central banks face different economic environments. With inflation remaining above target and unemployment so far under control, we expect the Fed to keep rates unchanged in January. Softer inflation figures in the months ahead, will likely allow the Fed to cut rates two more times in H1, bringing an end to the rate cutting cycle. In contrast, the ECB remains in a good place, as euro inflation is on target. We thus expect it to keep rates unchanged this year and next year.

The global economy is showing resilience in the face of the increased geopolitical risks and higher tariffs. This is especially visible in the US, where the Q3 growth figure reached an elevated 1.1% quarter-on-quarter. Growth is likely to remain robust in Q4, given strong export growth, decent demand and strong non-residential investments. The unemployment rate also remains under control for now, which together with still strong inflation, will keep the Fed on hold in January. We also slightly upgraded our outlook for China, given stronger industrial production and export resilience. The real estate market and weak domestic demand, however, remain important points of concern. In the euro area, the latest confidence indicators still point to a tepid growth outlook. German budgetary stimulus could spur a gradual improvement in growth dynamics in 2026, however.

Inflation dynamics have also improved across the world. In the US, inflation seems to have passed its peak as core inflation declined in December. In the euro area, headline inflation moderated further, and is now even somewhat below the 2% target. Core inflation, though more elevated, also remains under control. The ECB is therefore expected to keep policy rates at current levels for the foreseeable future. In China, headline inflation and producer produce price inflation accelerated in December, providing hopes that the country will avoid a deflationary spiral.

Despite the improved outlook, downside risks have increased markedly since the beginning of the year. For one, because tensions surrounding Greenland have mounted fast. Trump recently announced a 10% extra tariff on 8 countries (Denmark, Norway, Sweden, France, Germany, Finland, the Netherlands and the UK) in an escalation of his pressure campaign to acquire Greenland. The targeted countries had recently sent troops to Greenland as part of a ‘reconnaissance mission’, which was seen as a show of military support. As Trump walked back his threat in Davos, a full-blown trade war has been averted. That said, the US-EU tensions surrounding Greenland are not yet resolved and the risk of an escalating EU-US trade war remains on the table.

Meanwhile, uncertainty also remains high regarding the timing of the implementation of the trade agreement between the EU and the Mercosur countries. The agreement, which was signed earlier this month, has been put on hold once more as the European Parliament voted to send it to the EU Court of Justice to assess whether the EU-Mercosur agreement is in conformity with the EU treaties. Waiting for a ruling could delay the treaty’s implementation by as much as two years. The EU has the option to provisionally implement the agreement pending a ruling, but it is unclear whether the Commission will make use of this option.

Tensions in Venezuela have limited effect on oil prices

Oil prices posted another decline last month. Thanks to high non-OPEC+ supply and a higher OPEC+ production quota, they dropped by 2.2% in December to 60.9 USD per barrel. Prices even briefly dipped below 60 USD per barrel in mid-December. However, as the US started intercepting tankers transporting Venezuelan oil, oil prices recovered. The capture of Venezuelan president Maduro further pushed prices upwards earlier this month.

Venezuela has significant proven oil reserves (see figure 1). However, its oil production has dropped sharply from a peak of 3.5 million barrels per day in 1998 (5% of global production) to around 1 million barrels per day (less than 1% of global production). The current turmoil could lower oil production further in the short-term. However, given current oversupply, oil markets could easily absorb a reduction in Venezuelan oil output. In the longer run, the potential for a lifting of US sanctions and larger involvement by US oil majors could cause an important positive oil supply shock. Yet, the high extraction cost of Venezuelan oil, along with the decrepit state of Venezuelan oil infrastructure and still elevated uncertainty, may deter investment in Venezuela. Nonetheless, in anticipation of higher Venezuelan output, the futures curve flattened, with prices decreasing on the longer end of the curve.

Natural gas prices remained broadly unchanged last month, closing the month at 28 EUR per MWh. High US LNG supply is putting downward pressure on gas prices. However, low EU gas reserves (filled at 51.4% of total capacity) could put upward pressure on gas prices throughout this year.

Euro area inflation just below target

Euro area headline inflation closed 2025 at 1.9% year-on-year, down 0.2 percentage points from November. Core inflation - both the non-energy goods and services component - fell 0.1 percentage points to 2.3% (with 0.4% for non-energy goods and 3.4% for services). Energy price inflation experienced the steepest decline: from -0.5% in November to -1.9% in December, while food price inflation picked up slightly from 2.4% in November to 2.5% in December.

Inflation thus appears to be back on track for cooling. However, this remains mainly due to erratic movements in energy prices. Core inflation, on the other hand, remains stubborn. Since May 2025, core inflation has consistently been 2.3% or 2.4%. The breakdown of short-term dynamics of core inflation shows that after a temporary surge during the summer months, goods inflation cooled down sharply in the last quarter. But for services inflation, the momentum in the last months of 2025 was even slightly stronger than during the summer months (see figure 2).

This is probably due to a slightly slower than expected slowdown in wage growth, which is a key driver of services inflation in particular. In the ECB's December 2025 projections, the estimate for the annual increase in compensation per employee for 2025 and 2026 was raised by 0.6 and 0.5 percentage points, respectively, to 4.0% and 3.2%, down from 4.5% in 2024. The pace of wage growth is therefore still cooling, but less than initially anticipated. This may explain why services inflation in particular has slowed less than expected in 2025.

At the same time, a further slowdown remains likely, but it will be more gradual. We have raised our forecast for average core inflation in 2026 slightly from 2.0% to 2.1% (compared to 2.4% in 2025). For 2027, we expect a further decline to 2.0%. As energy prices will continue to exert a downward effect on overall inflation, total inflation is expected to average 1.7% in 2026 and 1.9% in 2027.

US inflation remains unchanged

Despite a very soft (and methodologically flawed) inflation print in November, headline inflation remained unchanged in December at 2.7% year-on-year (see figure 3). Core inflation moderated from 2.7% to 2.6% (and accelerated only 0.2% on a monthly basis). Within core components, goods remained unchanged. This is mostly due to a big drop in used car and truck prices. Other items, such as apparel and household furnishing and supplies, showed big increases, indicating tariff pressure remains important. In contrast to goods, shelter prices were strong (increasing at 0.4% month-on-month). This will likely be a one-off, given moderating forward-looking indicators. Services ex. shelter increased at a modest 0.14% month-on-month. The slowdown in services inflation is likely due to low wage pressures. Given slow increases and accelerating productivity, unit labour costs only increased by 1.2% year-on-year in Q3.

Within non-core components, energy prices increased modestly, thanks to a drop in gasoline prices. In contrast, food prices accelerated at a rapid pace. All in all, as inflation was in line with our expectations, we maintain our inflation forecast and expect 2.6% and 2.4% average inflation in 2026 and 2027, respectively.

Euro area waits for German growth engine to catch on

In the euro area, the economy seems to have ended 2025 on a somewhat false note. This can be inferred from business confidence surveys in industry and services. Both purchasing managers' surveys (PMI) and broader European Commission polls showed a drop in confidence in December. The improvement in consumer confidence also failed to continue in the last two months of 2025. Rather, there was a (slight) decline from an already low level.

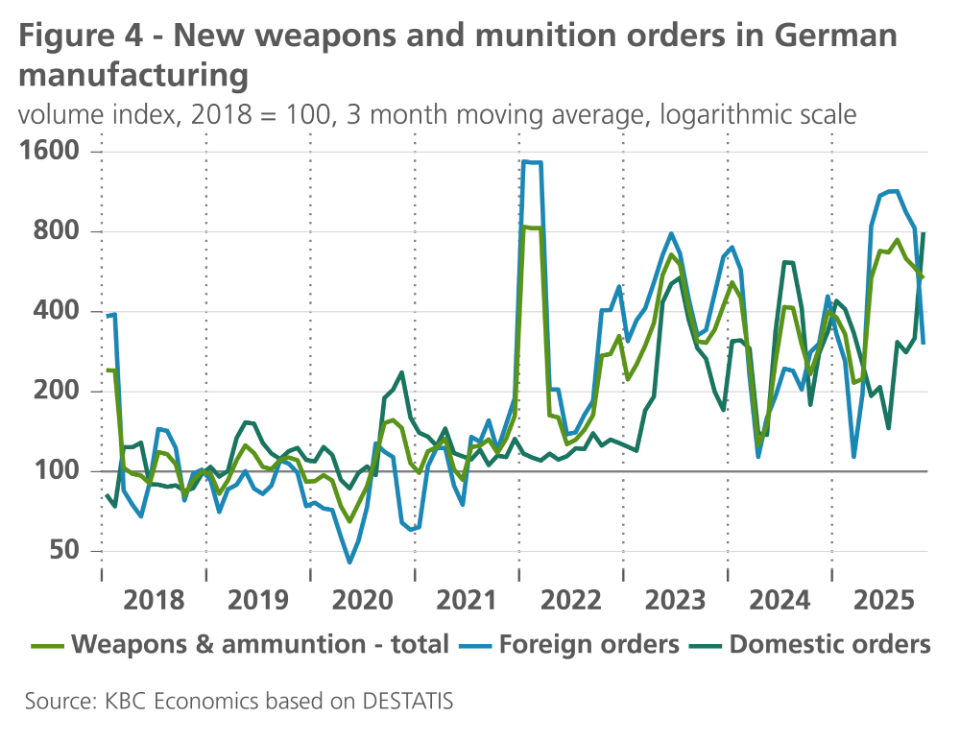

Fortunately, the confidence of entrepreneurs in the construction sector did continue to improve, although this improvement seems to be mainly evident among German construction entrepreneurs. This may well be linked to the start of the German government's investment programs for infrastructure improvements. In late 2025, defence orders - the other component of the comprehensive fiscal stimulus package - also gained momentum. Defence orders played an important role in the slight increase in new orders across all of German industry.

This is shown by an analysis of orders by industrial subsector (see figure 4). New orders at weapons and ammunition producers were almost eight times higher than the average in 2018 in the three months to November 2025, according to data from Destatis, the German statistical office. In particular, domestic orders were on the rise in the second half of 2025, while orders from abroad fell slightly. (In addition, it is notable that a significant part of the sharp increase in orders in the arms industry already dates back to immediately after Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.) By contrast, in Germany's traditional manufacturing sectors, which obviously account for a much larger share of German industry as a whole, the trend in new orders remains rather sluggish, at a level well below that of 2018: in the automotive industry, for example, well over 10% and in the chemical industry even nearly 25%.

This may explain why polls by the German research institute Ifo on the outlook for the next few months in German industry as a whole are not yet improving and German consumers also remain very cautious. Indeed, over the past five years almost 105,000 jobs (net) were lost in German industry, mainly in the automotive industry (almost 85,000). While the net increase of over 4,600 jobs in the arms and ammunition industry over this period may be a 44% increase for this sector, it by no means outweighs the substantial losses in the other sectors. It illustrates how fiscal policy stimulus has to compete with the structural adjustments that German - and by extension European - industry has to go through. Furthermore, all this is happening in a difficult, very uncertain geopolitical context, not least due to Europe's necessary repositioning vis-à-vis the US.

To assess the further course of the economic cycle - and to judge whether the fiscal stimulus will really get the German engine going - we will have to wait and see in the coming months to what extent the recent improvement in business confidence in the construction industry will be followed by a clear strengthening of construction activity. And whether this, together with the envisaged structural reforms, will provide a sufficient degree of a general confidence and activity recovery, allowing the German economy to lift neighbouring economies. There, precarious public finances necessitate a restrictive fiscal policy, which is likely to weigh on economic growth.

Nevertheless, we can expect 2026 to present itself as better than 2025, especially for the German economy. In fact, according to Destatis' first estimates, real GDP there would already have registered a modest growth of 0.3% (after adjusting for calendar effects) in 2025 after contracting by 0.7% in 2023 and 0.4% in 2024. For 2026, we expect Germany's GDP growth to average 0.8%, which is expected to strengthen to 1.6% in 2027. This would make Germany the euro area's growth engine, alongside Spain. That average real GDP growth in the euro area in 2026 is expected to fall from 1.4% in 2025 to only around 1% is solely due to a larger spillover effect from unexpectedly strong growth in early 2025, in anticipation of US import tariffs. Growth through 2026 will on balance be about the same as in 2025, but differently composed. That is, much more pulled by domestic demand - stimulated by fiscal policy - in Germany.

US growth is remarkably strong

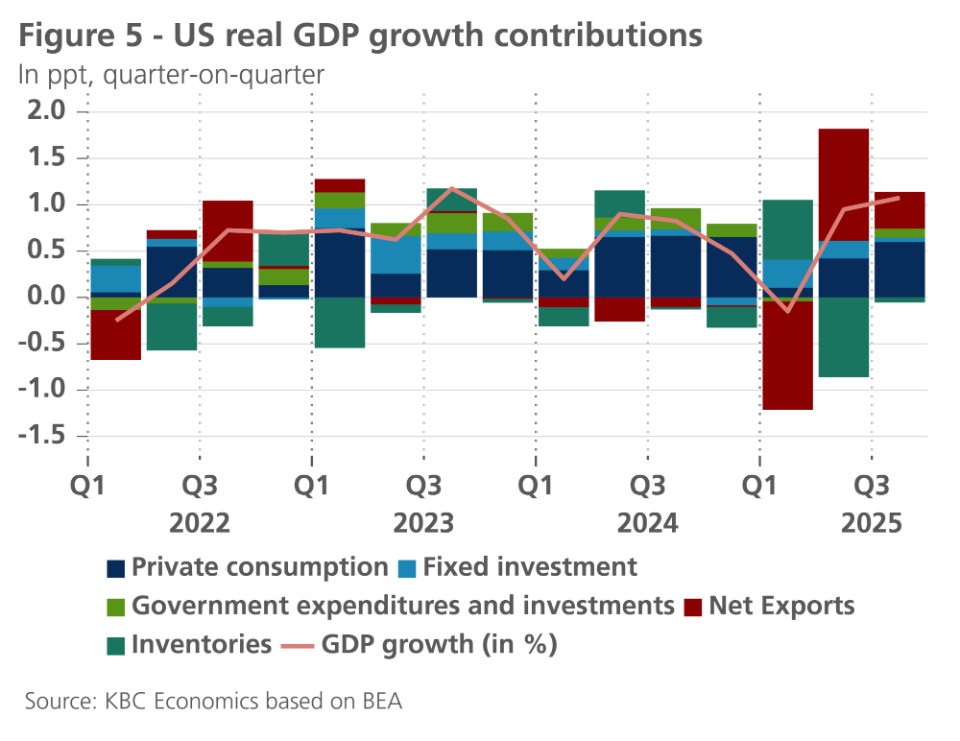

Despite higher tariffs imposed on most imports, the US economy continues to overperform. In Q3 2025, the economy grew at an impressive 1.1% quarter-on-quarter (see figure 5). The strong figure was mostly due to consumer spending, which contributed 0.6 percentage points to overall growth. As consumer surveys indicate, the growth is fueled by the highest earners which have seen rapid wealth growth in the past years. Net exports also made another important contribution (thanks partly to increased exports), though this was partially compensated by negative inventory growth. Fixed investment was weaker, as residential investments declined again.

The strong growth performance is likely to be maintained in Q4. Retail sales rose at a decent 0.6% month-on-month in November. Rising core capital goods orders also point to decent equipment spending in Q4. The trade balance also narrowed substantially, thanks in part to a large increase in services exports.

Given the slow job growth, the current growth overperformance might seem surprising. Non-farm payrolls were again weak in December. They grew by only 50k last month, while prior months were revised downwards by 76k in total. The low growth is partly caused by the on-going migration shock, which is hurting labour supply. Indeed, despite low job growth, the unemployment rate declined from 4.5% to 4.4% last month.

High productivity growth explains why the high GDP growth and weak job growth coexist. Labour productivity increased by 1.2% quarter-on-quarter in Q3 2025. Notably, productivity growth was more elevated in services than in manufacturing, which suggests that the rapid productivity might be AI-driven. Indeed, services are more impacted by the recent development of large language models than manufacturing.

For coming quarters, we expect growth to remain below potential as the effects of the on-going trade and migration shock filter through the economy. Nonetheless, given the large overhang effects from the strong Q3 and Q4 figures, we upgrade our 2026 GDP growth forecast from 1.7% to 2.3%. For 2027, we forecast 1.9% growth.

China hits the 5% growth target in 2025

Throughout 2025, the Chinese economy displayed remarkable resilience against a turbulent economic landscape. Real GDP grew 5% in 2025, meeting both the official government growth target and the growth rate of 2024. The economic resilience reflected strong export growth throughout the year, despite new US-imposed tariffs. In Q1 2025, front-running from US importers explained some of the Chinese export strength, but as exports to the US dropped sharply through the rest of the year, exports to all other regions of the world picked up enough to more than offset the decline to the US. Overall, net exports contributed 1.64 percentage points to the annual growth figure, up from 1.51 percentage points in 2024.

Meanwhile, domestic demand in China remains lackluster, held down by long-run structural challenges (an ageing population, high household debt, a weak safety net) together with the years-long downturn in the property sector and weak consumer confidence. Weak domestic demand exacerbates China’s overcapacity problems (which are evidenced by strong deflationary pressures), adding to tensions with trade partners. Meanwhile, efforts to address deflationary pressures among producers has contributed to a pullback in investment in recent months. As such, the structural slowdown in Chinese growth continues, with year-on-year growth decelerating from 5.4% in Q1 2025 to 4.5% in Q4 2025. We therefore upgrade our outlook for 2026 GDP growth only marginally on resilient external demand from 4.4% to 4.6%. For 2027 we expect growth to slow further to 4.2%. A recent uptick in headline inflation to 0.8% year-on-year reflects stronger food prices, while core inflation remains flat at a relatively low 1.2% year-on-year. After annual average headline inflation declined 0.1% in 2025, we expect a modest pick up to 0.8% in 2026 and 1.1% in 2027.

Fed takes more time on its path to 'neutral'

Compared to the Fed policymakers' December 2025 'dot plots', the current level of the policy rate (3.625%) is still above neutral (3%). Consequently, if no additional upside risks to inflation, or downside risks to the unemployment rate materialize, our baseline scenario remains unchanged, as we still expect the Fed to cut its policy rate by another 50 basis points in total to 3.125% in 2026.

However, that move is likely to be somewhat slower than we expected so far. After the December rate cut, Fed Chair Powell already indicated that Fed policy would be more data-dependent going forward. That was an implicit indication that an additional rate cut at each of the subsequent policy meetings would no longer be self-evident. That message was reinforced by the fact that already in December, two Fed governors voted in favour of an unchanged policy rate. Finally, Powell's observation that the policy rate is now in a range of plausible estimates of the neutral rate also indicated that the Fed would become more data-dependent.

Against that backdrop, the latest macroeconomic data make a more wait-and-see Fed more likely. Upward revisions to our US real GDP growth forecasts suggest that downside risks to the labour market have abated somewhat. Moreover, we keep our inflation outlook for US inflation unchanged. Both elements together reduce the need for the Fed to cut its policy rate already at its January policy meeting. That will probably not happen until March, by 25 basis points. The second 25 basis point rate cut to the Fed’s estimate of neutral is then likely to happen during the second quarter, provided no new unforeseen setbacks occur. In this scenario, the neutral policy rate is still reached faster than in the path the market is currently pricing in. According to the market, policy rates will not reach neutral until September.

We believe that the recent political attack on the Fed's independence will not affect the Fed's decision-making process. As an institution, the Fed has sufficient checks and balances to ensure that policy decisions are made solely on the basis of its policy mandate. One such element is the fact that interest rate decisions are made not by individuals but by the full FOMC of 12 voting members, including the heads of the regional Fed banks.

ECB still in a 'good position'

Unlike the Fed, the ECB has already reached the bottom of its easing cycle. With a 2% deposit rate, the ECB sees itself in a "good place" to address any future economic shocks. The ECB can afford this wait-and-see stance, since its inflation outlook, like ours from 2027-on, assumes inflation close to the 2% target. The relatively lower 2026 figure is likely to be only a temporary phenomenon based on the expected year-on-year development of energy prices, in particular. Also, the recent weakening of European confidence indicators are not so severe that the ECB should cut its policy rate again as a precautionary measure to support the business cycle.

What stands out in this context among current market expectations is, first and foremost, a strong belief that the 2% deposit rate will effectively be the bottom in this cycle. But in addition, the market is again pricing in an additional rate cut as the most likely alternative scenario. This contrasts with the market view, until recently, that the next interest rate move would be upward, which was fuelled by comments by ECB board member Schnabel, among others. The reason for this (limited) readjustment of market expectations is likely to be the somewhat disappointing recent eurozone sentiment indicators, and the prospect of below-target inflation in 2026.

German bond yields still have limited upside potential

Prior to the latest Greenland developments, both US and German 10-year government yields had remained largely unchanged over the past month, with a slight decline very recently for the latter. This decline may have partly to do with the fact that, as mentioned above, markets have priced in a (small) chance of an additional ECB rate cut.

Looking at real bond yields (adjusted for inflation expectations based on inflation swaps), the upward trend of German real bond yields remains clearly visible. That trend is still mainly based on an upward normalisation of the term premium. Since, in our view, that normalisation has not yet been completed, we still see some limited upside potential for German 10-year rates.

The US 10-year Treasury bond yield is likely to reach the 4.50% level during 2026 and stabilise there. We consider that level to be broadly in line with its 'fair value'. Our bond scenario assumes that, for the time being, the recent sharp rise in geopolitical uncertainty and political and legal attacks on the Fed will not cause a meaningful or sustained increase in the risk premium on US assets. Indeed, there is no clear sign of that yet in US government bond yields, equity markets or the dollar exchange rate. However, it is a risk that we continue to monitor closely.

USD likely to lose ground

Nevertheless, we confirm our expectation that the dollar exchange rate will lose some ground against the euro during 2026. This is caused by a remaining structural overvaluation of the dollar as well as the expected change in short-term interest rate differentials. While the market is convinced that the ECB will keep its policy rate unchanged and only prices in a next rate cut by the Fed in June,. if the Fed cuts in March as we expect, market expectations will adjust accordingly, which will put downward pressure on the USD vs the EUR.

EMU bond yield spreads have limited downside potential left

EMU governments' interest rate spreads against Germany remain at low levels and in some cases even slightly continue their downward trend. We do not expect a reversal in this for the time being. This trend is broad-based and not country-specific. However, markets still react to country-specific political events, as was recently the case in Portugal following the presidential election. An important driver is probably the rising trend of the German benchmark interest rate itself, more specifically of the term premium contained therein. After all, the days of scarce German government bonds are over. As the German risk premium itself is slowly but surely increasing, the relative risk premium of the other EMU member states is decreasing, and thus so are their bond yield spreads vis-à-vis Germany.

In addition, the downward trend may also still be supported by the existence of the ECB's Transmission Protection Instrument as a backstop and possibly also by a (perhaps unwarranted) market expectation of a tacit 'bail-out' intention from other EMU governments should the public finances in another member state get into serious trouble. After all, the last thing the eurozone needs in the current geopolitical context is another European debt crisis.

All historical quotes/prices, statistics and charts are up-to-date, up to 19 January 2026, unless otherwise stated. Positions and forecasts provided are those of 19 January 2026.