Most recent Economic Perspectives for Central and Eastern Europe

Bulgaria: integration into the euro area and the 2026 fiscal framework

Bulgaria recently released its first inflation estimate as a euro area member, providing an early glimpse into the price dynamics following the currency adoption. Contrary to historical fears that the euro introduction would lead to a sharp spike in the cost of living, the data indicates a moderating trend. January CPI inflation was 3.6 % year-on-year, down from 5.0 % in December. HICP inflation fell even more sharply to 2.3 % year-on-year in January, compared to 3.5 % in December.

The month-over-month inflation rate came in at 0.7%, driven by specific sub-sectors rather than a broad-based currency-related repricing. The groups with the highest monthly increases include "Personal care, social protection and miscellaneous goods and services", "Insurance and financial services", and "Restaurant and hotel services".

Parallel to the euro adoption, the Bulgarian Parliament has advanced a rigorous budgetary framework for 2026 that attempts to balance ambitious social spending with the fiscal limits required of a eurozone member. The 2026 State Budget Bill, adopted at its first reading in late January, projects a fiscal deficit of 3.0% of GDP and moderate economic growth of up to 2.7%. Total public expenditures are planned at 46% of GDP, which would be a 12% increase compared to 2025.

The significance of Bulgaria’s euro adoption extends beyond the immediate technicalities of currency exchange. As Bulgaria’s interest rate policy is directly determined by the ECB Governing Council now and the "smidgen of currency risk" that persisted even under the previous currency board arrangement has been eliminated, lower sovereign risk premiums should be expected.

Czechia: economic resilience and monetary patience

Czech real GDP growth is estimated to have reached 2.5% in 2025. We forecast a slight slowdown for the next two years, to 2.3% this year and 2.2% in 2027. The growth, so far almost exclusively driven by domestic demand, should be additionally supported by fixed capital investment, rising 3% year-on-year at least both in 2026 and 2027. The ongoing sound consumer spending has been fueled by continuing real wage growth and a gradual reduction in the elevated household saving rate.

The CNB decided to keep the two-week repo rate unchanged at 3.50% in February. The sixth consecutive pause in the easing cycle reflects the Board’s concern that a rapid reduction in interest rates, combined with a moderately expansionary fiscal policy, could refuel services and property price inflation.

The average national CPI inflation rate reached 2.5% in 2025. The CNB’s assessment is that the current 3.5% rate is only slightly above the neutral level. Both the new CNB forecast and the Governor's comments clearly see this year's decline in inflation (+1.6 % year-on-year in January) as a one-off phenomenon due primarily to cheaper energy. What will determine the movement of rates will be the further development of wage dynamics and inflation in services - the latest figures still point to increased dynamics in both areas.

Hungary: targeted growth through fiscal expansion and high-interest caution

Following a stagnant 2025, where GDP growth is estimated at only 0.3%, the Hungarian government has projected a rebound to 4.1% for 2026. However, end-2025 and early 2026 data present a complex picture, based on which we forecast annual real GDP growth will reach only 1.9% this year and 3.0% in 2027.

External trade data published in January showed that Hungary’s trade surplus shrank by 8% in 2025 compared to the previous year. The narrowing was caused by import growth (6.5%) slightly outpacing export growth (6.0%), a trend that reflects the revival of domestic consumption amidst a sluggish European industrial environment.

Economic sentiment worsened in January 2026, falling to 95.1 from 100.0 in December, with particularly sharp declines in the industrial and services sectors.

The CPI inflation rate slowed to 3.3% in December 2025, matching expectations, but core inflation remained at 3.8%, close to last summer´s values. Service sector inflation, in particular, rose to 6.8%, suggesting that the disinflationary process is encountering resistance. We expect the average harmonised CPI inflation to be 3.3% this year and 3.5% in 2027, both lower than the 4.4% reported for 2025.

The Hungarian central bank decided to keep the base rate at 6.50% at its January meeting. The MNB’s commentary had a "hawkish" tone. The central bank noted that while headline inflation briefly fell within the tolerance band, underlying inflation indicators have accelerated. The MNB remains cautious of the minimum wage hike and other government income-increasing measures, which could sustain elevated services inflation. We expect the central bank to cut its base rate by a total of 50 basis points during 2026, starting in the third quarter. The forint strengthened following the MNB meeting, testing the 380 level against the euro, which the MNB views as helpful for anchoring inflation expectations.

Hungary’s 2026 budget, which was described by the government as "Europe’s largest tax cut program," prioritises families and pensioners. We project that the budget measures will cause the government deficit to rise to 5.3% of GDP in 2026, up from 5.0% in both 2025 and 2024. The Fiscal Council of Hungary also sees “material risks" to the deficit target due to uncertainties surrounding the availability of EU funds and potentially lower-than-planned economic growth.

Slovakia: navigating fiscal consolidation and industrial slowdown

Slovakia is currently facing the most significant macroeconomic challenges in the region, as it attempts to implement a massive fiscal consolidation package while its industrial sector, particularly automotive manufacturing, struggles with global trade headwinds.

Latest available data reveal a 4.5% year-on-year drop in industrial production in November 2025, following a 3.8% drop in October. The ninth contraction of 2025 was led by an 18.8% plunge in electricity and gas supply and a 6.7% decline in transport equipment. The slowdown in the automotive sector - the engine of the Slovak economy - is attributed to a high comparison base and the early impacts of US import tariffs, which have led to a decrease in export orders.

Despite the industrial slump, the trade balance surplus rose 2.7% month-on-month in November. This was partly due to an expansion of capacity in some automotive segments earlier in the year, although the outlook for the second half of 2026 remains pessimistic as global trade tensions persist.

At the end of January, the IMF mission projected GDP growth in Slovakia to hold steady at slightly below 1.0% in 2026 (consistent with our forecast). The Fund also assessed the government’s 2026 consolidation package as "broadly appropriate" but warned it was driven by "last-minute political compromises". Our outlook for the government budget deficit has remained unchanged: -5.0 % of GDP this year and -5.5 % in 2027.

Regarding average harmonised CPI inflation, we have slightly adjusted our forecast by cutting the 2026 forecast (from 4.2% to 3.9%) and marginally raising the figures for next year on the back of the removal of energy price subsidies and the VAT hike.

The labour market in Slovakia is expected to remain stable with end-year harmonised unemployment rate oscillating between 5.5% and 5.9% till the end of 2028. The real wage growth is expected to be negative in 2026, though, which will further weigh on private consumption.

Box 1 – New opportunities for CEE, but much work remains under the EU–India Deal

On 27 January 2026, the EU and India announced their Free Trade Agreement in New Delhi, creating one of the largest free trade areas globally, covering nearly two billion consumers and about 20% of world GDP. The agreement delivers extensive tariff liberalisation: the EU will remove tariffs on over 90% of tariff lines (91% of trade value) and India on 86% (93% of trade). With partial liberalisation included, coverage rises to 99.3% for the EU and 96.6% for India.

India’s major concessions concern industrial goods, where tariffs currently average more than 16%. Duties on chemicals (up to 22%) will be largely removed immediately; cosmetics will be liberalised over 5–7 years; plastics will be partly liberalised at entry into force and fully within seven years; and car parts over 5–10 years. Most tariffs on textiles, apparel, ceramics and boats will be eliminated immediately, while machinery will be liberalised in two stages over up to ten years.

In agrifood, liberalisation is more selective. Tariffs on olive oil (up to 45%) will end immediately or after five years. Duties of up to 55% on non alcoholic beer and certain fruit juices will be removed after five years. Processed foods facing 33% tariffs—such as confectionery, pasta, chocolate and pet food—will see these duties eliminated either immediately or gradually. Sheep meat tariffs (33%) will be phased out. High tariffs on alcoholic beverages—in some cases 150%—will fall to 30% for wines, 40% for spirits and 50% for beer. EU exports of fruits will gain improved access through Tariff Rate Quotas.

We model the direct and indirect effects of the announced measures on economic activity through tariff reductions. The phased implementation is taken into account, and we make assumptions about the demand response to the resulting price decreases. The model includes multiplier effects through international production chains using input output tables, and it adds an income multiplier.

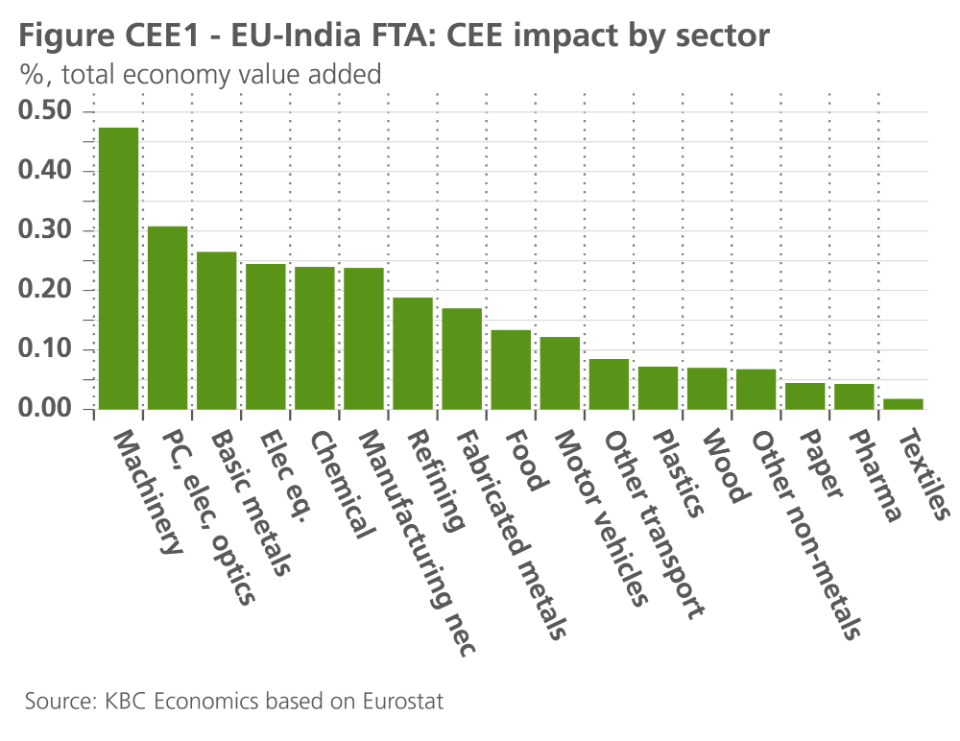

In Figure CEE1, the effect of tariff reductions on specific sectors in Central and Eastern European countries is shown, measured as the percentage increase in value added. The machinery sector would gain the most, by more than 0.4%. This is not surprising, as machinery and electrical equipment constitute the largest export sector to India. Other CEE sectors would also benefit, including electronics, basic metals, plastics and chemicals. Motor vehicles will not benefit as much from the agreement, even though the tariff reduction in this sector is the largest, falling from 110% to 10% through phased cuts. One must take into account the very difficult nature of entering the Indian car market, where more than 90% of market share is held by Asian manufacturers.

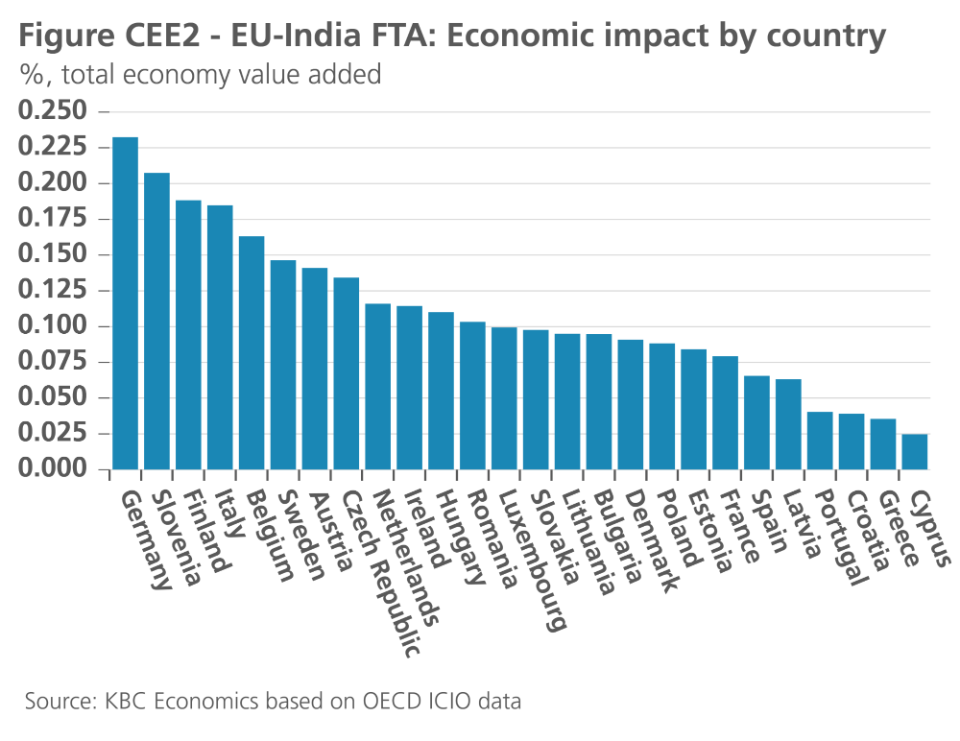

Figure CEE2 shows the economic gains from the Free Trade Agreement across EU countries. For CEE economies, namely Czechia, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria, the revenues from the deal are relatively moderate in value added terms. Czechia and Hungary appear in the upper middle of the distribution, reflecting their relatively high exposure to India through machinery, automotive components, electrical equipment and industrial intermediates—sectors where Indian tariffs are reduced gradually but significantly. The Czech Republic also benefits from close trade ties with Germany. Lower gains for Slovakia, Bulgaria and Poland may reflect their relatively low export shares compared with other EU countries.

Based on existing trade structures, the gains appear quite limited. The Indian market is fragmented and difficult to penetrate, and CEE countries have fewer established trade links with India than some other European economies. India also offers greater access to low cost labour, which may partly reduce the competitive advantage of the CEE region within Europe. It will therefore be essential for CEE countries to invest in modernisation, education and advanced technologies. Nevertheless, there are opportunities for higher value added production, including mechanical engineering, automotive components and the defence industry. The intention to work more closely together was already evident. Even before this agreement, many CEE countries had signed strategic partnerships with India.