Economic Perspectives April 2020

Read the full publication below or click here to open the PDF.

The corona crisis is a major shock to the global economy. Economic growth will move into negative territory in the euro area and the US, but our base scenario envisages a strong recovery in 2021. This base scenario is, however, subject to major uncertainty. In general, risks are tilted to the downside.

The epicentre for the covid-19 virus outbreak is on the move from China over Europe to the US. It is clear that all countries in the world will be affected, leading to a globally synchonized growth decline. In combination with lower oil prices, due to a negative supply and demand shock, this will result in major deflationary pressure on the global economy.

Also emerging markets have been hit hard by the covid-19 crisis, but the health and economic impact could be even more severe and longer lasting than what’s expected in advanced economies. Weaker public health systems, higher inequality and poverty, more limited fiscal space, and external vulnerabilities are factors that may exacerbate the coronavirus shock in emerging markets. There are, however, significant differences between the countries with some having better macroeconomic fundamentals and fewer external vulnerabilities (e.g. emerging Asia) than others.

Fiscal and monetary policy initiatives aim to mitigate the economic impact of the corona crisis and to boost the recovery. However, policy reactions differ across countries, even within the EU. Monetary policy is expected to stay extremely accomodative in the future.

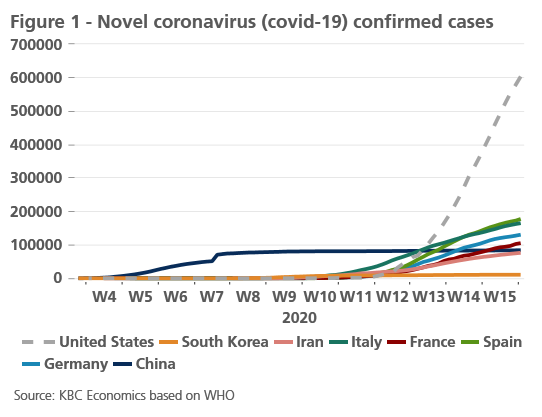

The outbreak and international spread of the covid-19 virus is undoubtedly the main event now dominating the international economic outlook. Primarily, the corona crisis is a major health crisis and a human tragedy due to the loss of many lives despite all precautions and health care responses. Recent figures indicate that the pandemic’s epicentre shifted from China over Europe to the US (figure 1). While the number of infected people seems to have stabilized in China, Europe is still struggling to cope with the situation. Nevertheless, among the largest economies, the US is facing the most gigantic challenge which at present the US healthcare system is struggling to deal with. The covid-19 virus continues its international spread, reaching all countries in the world, making it a true pandemic as designated by the World Health Organization (WHO).

The virus itself as well as numerous policy responses to contain its spread are having a tremendous and most likely unprecedented impact on the global economy. As most countries introduced quarantine measures and in many cases far-reaching lockdown policies, economic activity slowed down substantially and was almost completely halted in certain sectors. There is no doubt that the covid-19 virus has changed the macro-economic outlook for the global economy. Most importantly, global growth will tumble as suggested by recent forward-looking indications in sentiment indicators. Both manufacturing and services are heavily impacted. Particular sectors like restaurants, tourism and retail trade are facing unprecedented drops in their economic activity as the corona crisis causes a negative demand shock. Simultaneously, the corona crisis is a negative supply shock too. In its early stage, while the covid-19 virus outbreak was still considered a major challenge to the Chinese economy alone, it became clear that global supply chains would be hit. This has only worsened as not only Chinese factories, but gradually factories in most countries are now facing production challenges and logistic difficulties to source inputs and service their international clients. Not surprisingly, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) recently indicated that it expects a major drop in global trade in 2020.

Despite the negative impact of the corona crisis on the global economy, it is important to emphasize that this is not a normal recession, but a temporary standstill due to the virus containment measures. One could compare it with the following: “The car doesn’t drive because the traffic light has suddenly turned red, not because the engine has seized. Once the light turns green, the car will drive again, although some cars will restart faster than others.”

Due to the corona crisis, the synchronized growth slowdown in 2019 won’t be followed by a widespread international recovery, as many expected before the covid-19 pandemic, but rather by a major economic depression. The good news, however, is that this shock is due to a major health crisis and not due to notably poorer economic dynamics. The fundamental features for the global real economy before the virus outbreak weren’t bad at all: many economies were at or near full employment, services activities were compensating for the decline in manufacturing activities that suffered in particular from the US-China trade war and the Brexit chaos, and private investment was growing in a low interest rate environment. The corona crisis will shake the structure of the global economy, but it’s unlikely to fundamentally derail the global economy from its long-term growth path. While it is still too early to assess the long-term impact of this corona crisis, it is likely that certain things will change in the global economy in the aftermath of the corona crisis. A case in point is the international struggle to get sufficient medical supplies. One may expect that governments will aim to improve their access to such medical products. From a business cycle perspective, we believe that the economic shock caused by the covid-19 virus will be heavy, but short. Moreover, the recovery will be boosted by various policy initiatives to mitigate the economic damage (see further). Hence this will lead to a very dynamic episode in the global business cycle with a major growth decline in 2020 followed by a remarkable recovery in 2021.

Despite this general expected growth pattern, the future virus evolution and policy reactions to it are subject to substantial uncertainty. This makes conventional forecasts of limited value given the potentially wide range of possible outcomes. Therefore we work with multiple scenarios to assess the future economic outlook. Apart from the base scenario, we distinguish between a more optimistic and a more pessimistic scenario. These three scenarios are distinct from each other in terms of the virus evolution, the lockdown measures and the economic implications. In our base scenario we assume that the current lockdown measures will be continued, by and large, in the euro area as well as in the US throughout the second quarter. The high human toll of the covid-19 virus makes it unlikely that governments will quickly relax precautionary measures. After all, the search for large-scale tests to identify infected people is still in its infancy. Moreover, the search for a vaccine will most likely take much longer. Only in the third quarter, does this scenario envisage that the precautionary measures will be gradually lifted. Consequently the first and second quarters will be hit substantially in the euro area, while the US follows – as the covid-19 virus reached the US later than Europe – with a substantial drop in the second quarter and a minor drop in the third quarter. Hence the quarter-on-quarter recovery starts only in the third quarter in the euro area and in the fourth quarter in the US. The recovery continues into 2021 leading to a strong year-on-year growth rebound in the calendar year 2021.

Compared to the base scenario, our ‘optimistic’ scenario assumes a shorter period of lockdown or disruption from far-reaching precautionary measures. Such a scenario could come about if extensive testing for covid-19 can be implemented or simply because society increases the pressure on governments to lift currrent lockdown policies. Such a scenario would automatically translate into a more limited downfall in economic growth. Finally, our ‘pessimistic’ scenario assumes that the covid-19 virus is not under control until a vaccine becomes available. As society may be opposed to long periods of lockdowns, governments might opt for on-off lockdown periods to migitate the impact on the health care system. Alternatively, it could be the case that there are periodic outbreaks of the virus forcing the repeated re-introduction of health related curbs on economic activity. Such a scenario implies that economic activity could be restarted soon, but would also be forced to shut down again later on. In general this will imply that the recovery from the corona crisis will take much longer.

We assign probabilities to each of these scenario. At the moment, we’re giving a 50% probability to the base scenario, 15% to the optimistic scenario and 35% to the pessimistic scenario. Hence risks are tilted to the downside.

Numerical scenarios

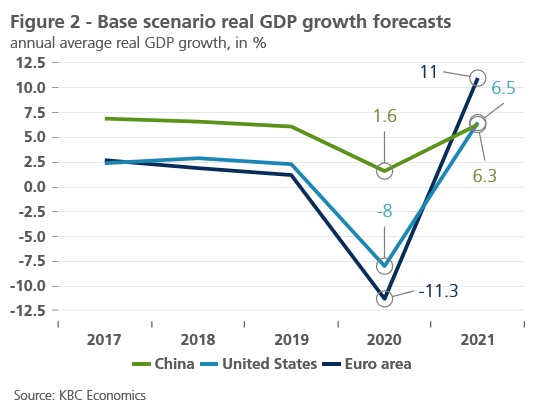

Our base scenario is shown in figure 2. In terms of annual numbers we expect a similar pronounced V-shaped pattern in all major economies. Note that one could call it rather a U-shaped pattern on the basis of a quarterly numbers, taking into account the gradual recovery in the second half of 2020. However, while the broad shape of the swings in activity are similar, the scale of impact differs substantially.

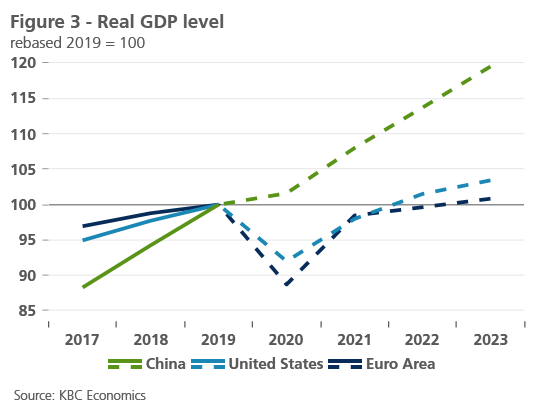

In absolute terms, euro area growth is likely to be hit more than the US due to the drastic precautionary policy reactions in most European countries and the slower and more limited fiscal reaction. Europe’s international openness to trade and investment as well as a weaker starting point in terms of lower growth in 2019 will also play against Europe. For the euro area, we expect growth to decline by 11.3 %, while US growth will drop by 8 % in 2020. We expect a similar recovery in 2021 in both regions, namely 11 % in the euro area and 6.5 % in the US. For China we presume a growth of 1.6 % in 2020, down from 6.1 % in 2019, and a recovery to 6.3 % in 2021. Under our base scenario this pattern implies a rather fast return to the long-term growth path, although it will take a while, in particular in the euro area, before the full effect of the corona crisis will be absorbed (figure 3).

Compared to the base scenario, our optimistic scenario has a milder V-shaped pattern. In the pessimistic scenario the growth decline in 2020 is larger, ranging from -14% in the euro area, over -10% for the US to 0.4% for China. In 2021 one won’t see a similar recovery in the euro area and the US yet. Euro area real gdp growth will equal -3.2% in 2021, against -2.8% for the US. One has to wait for 2022 to get a stronger recovery. All figures are available in table 1.

Hopeful news from China

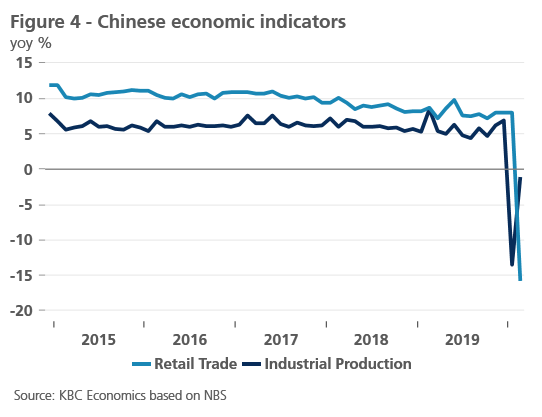

In recent weeks, the number of new cases as well as covid-19 casualties dropped substantially throughout China. The Chinese city of Wuhan is considered the initial epicentre of the covid-19 pandemic. Symbolically, social and economic life is restarting in Wuhan. Meanwhile, Chinese economic indicators such as vehicle sales are the first to signal that economic activity is likely to recover soon after the virus gets under control. Additional March data suggest that the recovery is more dynamic in the manufacturing sector compared to the services sector, which in turn reflects the fact that businesses and factories have reopened, but consumers are still very cautious. Retail trade contracted sharply again in March (-15.8% yoy), while industrial production only contracted by 1.1% yoy in March, compared to a 13.5% contraction in February (Figure 4). In general, what more recent data out of China suggest is that the relative bounce-back after the lockdown can be strong, but that in terms of output levels, it will take more time to return to the pre-covid-19 scenario.

The fact that economic life in China is restarting relatively fast after the start of the virus outbreak is hopeful news for the global economy. Moreover, as a major economy, the Chinese recovery contributes to mitigating the economic shock in western economies. The Chinese demand for western goods as well as the Chinese supply of products will gradually recover. Despite these optimistic signals one has to be cautious. First, China remains vulnerable to the virus as a recent number of new cases indicate that people travelling from abroad may import the virus again into China. Second, the production and sales decline in the Chinese economy was sizeable, hence a full recovery may take a while and will be more difficult given the slowdown of the global economy.

We expect Chinese real GDP growth to start to recover already in Q2, but growth in year-over-year terms will remain weak compared to China’s previous growth path. This is because the threat of a new wave of covid-19 cases is still a risk in China, the very weak growth we expect globally in Q2 will weigh on China’s growth, and confidence will likely be slow to fully recover. Overall, we expect China to grow only 1.6% in 2020, compared to 6.1% growth in 2019. In 2021, however, we expect annual growth to recover to 6.3%.

Struggle in Europe

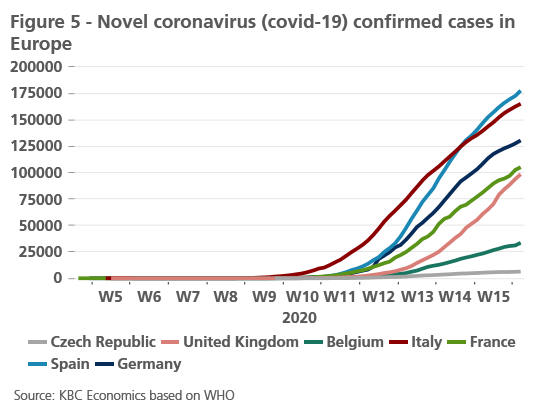

After the initial outbreak in Northern Italy, the covid-19 virus succeeded in spreading widely across most of the European continent as well as the UK and Ireland (figure 5). Despite initially different approaches, most European countries turned to a broadly similar strategy of far-reaching quarantine and lockdown measures. The ultimate purpose is to reduce the near-term inflow of patients into hospitals as the number of hospital beds and other medical equipment would be insufficient to treat all patients simultaneously. Most European countries appear to be succeeding in this strategy. However, in certain regions of Italy and Spain, it is clear that hospitals have been overwhelmed by the number of covid-19 cases.

On the economic front, European governments are taking similar initiatives too, but there are also clear differences. Throughout Europe, governments aim to mitigate the impact of the corona crisis through temporary fiscal support to businesses and households. Fiscal support should help companies and individuals to survive the temporary economic shock. The financial sector is strongly involved to facilitate and support these temporary solutions. As such, the full force of the crisis can be avoided, in particular for fundamentally sound firms and households that face a temporary drop in their incomes. Special attention is paid to the situation in regard to the labour market. Most European countries introduced some kind of temporary unemployment schemes (see Box 1). Their purpose is to enable a faster restart after the lockdown measures are lifted and to avoid people losing jobs permanently. In the less flexible continental European labour markets, in particular, these kind of measures make sense. By contrast it might be expected that Anglosaxon countries like the UK and Ireland could face a more substantial increase in their unemployment rates. Apart from those transitory policies a debate is now underway in many countries to come up with more structucal fiscal support to boost the recovery through public investment. However, European countries differ substantially in the available fiscal space to finance these kind of major policy actions. Both the temporary policies and an eventual increase in structural investment will undoubtely lead to large fiscal deficits and increasing public debt ratios in all European countries. Hence the corona crisis will cause a major deterioration in public finances. Given the exceptional nature of the corona crisis, most economists agree that these circumstances are a valid argument for this kind of policy reaction.

It is very regrettable that a major crisis like this corona crisis has led to European countries dealing with the issue separately. European coordination and cooperation remains limited. Health care is obviously a national competency and hence there isn’t much the EU can do apart from some international coordination. In terms of economic policies the EU has more responsibilities, but unfortunately it lacks the automatic tools in scope as well as size to act fast and convincingly. There are no automatic fiscal stabilizers at the EU level. The common EU budget is much too small to deal with a major economic shock nor has it been designed for any role in such circumstances. Hence the EU can only provide support if new budgets and/or new instruments are created, similar to what happened after the global financial crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis.

So far, negotiations in the Eurogroup and the European Council have not gone smoothly. Individual European governments clearly disagree as to the kind of support mechanisms that should be launched and in particular on how and to what extent financial solidarity should underpin such support. The Dutch government has been the most visible opponent of massive financial support to countries hurt by the crisis, in particular to Southern European countries. However, the Dutch view is shared to varying degrees by a number of other (richer) EU member states. The latest compromise resulted in a measure of European support to small and medium sized enterprises as well as to temporarily unemployed people. The European Investment Bank as well as the European Stability Mechanism will be used to provide some fiscal support to countries in need. However, it is clear that these European initiatives will be insufficient to cope with the corona crisis. It remains to be seen whether additional European initiatives will be launched in the future. If not, there is a risk that the European economy will face a more difficult recovery period as well as longer-term negative consequences of this unfortunate economic shock.

As European countries are hurt to various extents by the covid-19 virus and as policy reactions to the corona crisis differ across countries, we expect that European countries will face different growth dynamics. However, the general pattern remains the same: a major drop in economic growth in 2020 followed by the recovery in 2021. The magnitude of the shock as well as of the recovery differs, however, across countries (table 2).

Box 1: Temporary unemployment a crucial pillar in avoiding a prolonged recession

Estimates for average real GDP growth in 2020 are written in blood red ink. The seldom seen negative numbers are the result of sudden stagnation in large parts of the economy due to covid-19. Nevertheless, there is also an optimistic element in the severely negative growth figures. After all, the base scenario assumes that the economy will largely recover as measures against the spread of the virus are lifted. In other words, the stagnation of the economy will not trigger a downward spiral of mass redundancies and bankruptcies. A crucial pillar for this scenario is the schemes of temporary unemployment and income support, which are now being activated, extended or created in many countries.

A sharp drop in turnover normally encourages companies to lay off employees. However, by this production capacity is definitively lost. When demand later picks up again, they have to look for new suitable employees. These employees have to learn the production processes again. This takes time (and costs) and slows down the restart of the economy. Companies with highly specialised employees will try to avoid dismissals as long as possible in the event of a drop in demand. In this way, they prevent the search and start-up costs when demand recovers. However, a sudden and very sharp drop in demand, such as today, reduces their financial breathing space for this. Moreover, the corona crisis primarily affects service sectors, where employees are sometimes a little less specialised and companies will still want to say goodbye to them sooner.

Temporary unemployment or income support systems help to prevent this. Belgium has long been familiar with the system of temporary or technical unemployment. Internationally, reference is often made to the German system of Kurzarbeit. It allows companies in certain circumstances to limit the working hours of employees. A government allowance then compensates, at least partially, for their loss of income. Thanks in part to Kurzarbeit, unemployment in Germany hardly rose during the deep recession after the financial crisis of 2008. Belgium, too, experienced only a limited rise in unemployment at that time;

Anglo-Saxon economies did not have such systems. They generally have more flexible labour markets. Economic shocks cause unemployment to rise faster and more sharply. In normal circumstances, a stronger recovery follows. Nevertheless, it reduces macroeconomic stability. Especially when, as at present, labour-intensive sectors with sometimes relatively low wages are hit. The loss of purchasing power as a result of mass redundancies can then sharply amplify the fall in demand in the economy and fuel a negative spiral. This will further increase the economic damage. The recovery from a deep crisis then threatens to drag on for longer, resulting in even more economic damage. As unemployment lasts longer, skills are lost. Ultimately, the long-term growth potential of the economy is eroded.

Many countries are now relying heavily on systems of temporary unemployment and income support. Existing systems are being extended and conditions made more flexible. The abruptness and scale of the economic shock make rapid and smooth implementation essential. The UK is creating a system, and even in the US small businesses receive government support if they retain workers. Systems are also being set up in Central Europe, often in the form of wage subsidies to companies, similar to the French system of temporary unemployment.

Temporary unemployment and income support systems are crucial in a crisis like this one. But they also cost the government a great deal of money. In principle, however, they are temporary expenditures. They do not structurally worsen public finances. They do not pose a problem if the objective of a rapid pick-up in economic output as soon as demand picks up is achieved. If that does not happen, or is insufficient, a problem for public finances will arise. Unemployment then becomes permanent and requires a different economic policy.

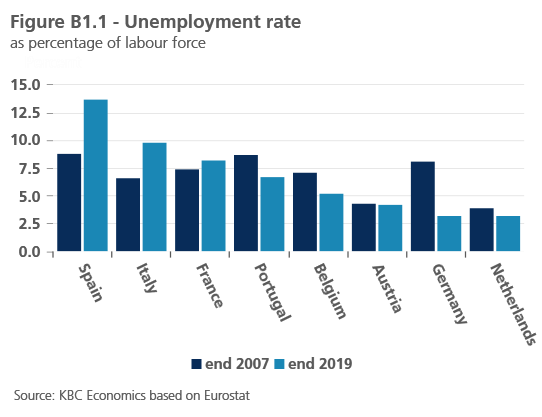

In this context, Spain deserves special attention. Despite strong economic growth in recent years, unemployment has still not returned to its pre-financial crisis level of end-2007 (figure B1.1).

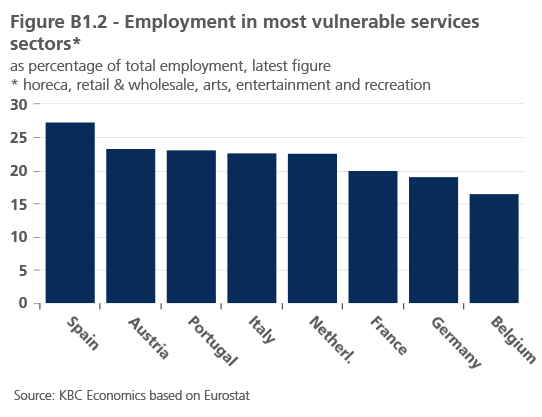

Today, the Spanish labour market once again appears to be one of the most vulnerable in Europe. More than a quarter of total employment is in services sectors which are very sensitive to corona crisis measures. This is significantly more than in the other (medium) large economies in the euro area (figure B1.2). The risk that part of the temporary unemployment will eventually become permanent is highest there.

Alle historische koersen/prijzen, statistieken en grafieken zijn up-to-date, tot en met 9 april 2020, tenzij anders vermeld. De verstrekte standpunten en prognoses zijn die van 9 april 2020.