Germany’s balanced budget could tip the scales for the worse

The gloomy economic outlook has prompted the ECB to postpone the normalisation of its interest rate policy. Meanwhile, the OECD has highlighted the need for an adjustment of the European policy mix with more structural reforms in all euro countries and fiscal stimulus in surplus countries such as Germany. Germany is pursuing an expansive fiscal policy, but with a handbrake: it is holding on to the schwarze Null (or a balanced budget). To insist on this stubbornly, even if it means reducing fiscal stimulus to account for a weaker economy, would be a policy error, because Germany, too, can use structural reforms with more investment. With a balanced budget, the German government would tip the scales negatively for not only Germany, but the entire eurozone.

ECB can’t do the job on its own

Growth prospects for the euro area economy have dropped at a rapid pace in recent months. Italy fell into a recession and the German economy hardly grew in the second half of 2018. The poorer external environment, not least due to the trade war between the US and China, played havoc with German exports, which have been an important engine for growth in recent years. Temporary developments also threw a spanner in the works. They will fade, meaning excessive pessimism is not justified for the time being. Initial estimates of real GDP growth in the first quarter of 2019 confirm this. However, a very strong economic recovery is not expected.

As a result of the economic slowdown, the ECB is reconsidering its policy. The general consensus is that it is only likely to start raising interest rates in 2020 rather than after the summer of 2019, as previously expected. By keeping its policy extremely loose for longer, the ECB hopes that inflation will evolve to its target of 2%. Despite the extremely flexible monetary policy that has been in place for a very long time, there is little evidence of a significant, sustainable acceleration in inflation. It is also difficult to see how an expansive monetary policy on its own can substantially increase inflation. Indeed, the low inflation rate reflects not only the slowdown in the economy, but also the restoration of competitiveness in peripheral euro area countries. This means that their inflation rates must remain below that of Germany. As long as the latter remains below 2%, average euro area inflation cannot really get close to 2%. In this respect, it is not so much the ECB as it is the German policymakers who hold the key to higher inflation (see also: KBC Economic Research Report: More inflation in the eurozone? Germany holds the key and KBC Economic Opinion: " In the long run, we're all dead." But what now, ECB?). The ECB will not be able to do the job on its own. Maintaining extremely low interest rates may even be counterproductive for economic growth. The eurozone and Germany need a better policy mix.

Need for a better policy mix

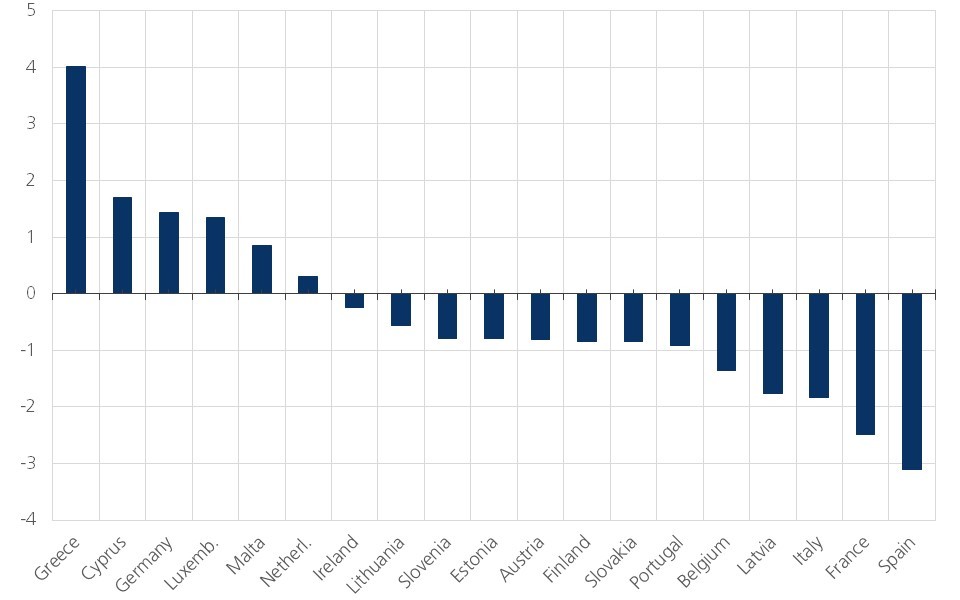

In the most recent update of its economic outlook, the OECD points out that better coordination of macroeconomic policies in the euro area would increase the effectiveness of monetary policy. The institution advocates complementing the ECB’s low interest rate policy with a temporary stimulus through the government budgets of those countries that have the room to do so. It envisages a three-year public debt-financed investment programme amounting to 0.5% of GDP annually in Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Ireland, Finland, Slovakia, Slovenia and the Baltic States. These are countries with a structural budget surplus or only a small deficit (Figure 1). All euro-area Member States should simultaneously promote structural reforms. In 2019 and 2020, this would stimulate euro area growth by a quarter of a percentage point. In the longer term, economic output would be a full percentage point higher. The IMF and the ECB previously published studies with similar conclusions.

Figure 1 - Structural budget balance general government (2018, as a % of potential GDP)

Such macro-economic policy coordination should in principle take place in the EU in the context of the European Semester. This provides for all EU countries to submit a reform and stability or convergence plan to the European Commission at the end of April. It allows for an assessment of structural economic reforms and medium-term fiscal policy. Now should therefore be the ideal time to implement the OECD’s recommendations. Only the future can tell whether this will happen. Expectations for structural reforms are already being tempered by the imminent European elections and the emerging success of populist parties. Germany is the only significant country with budgetary room for manoeuvre (Figure 1). The eurozone itself does not have the fiscal clout (see KBC Economic Opinion Enhance the eurozone's fiscal capacity).

Schwarze Null should not remain an obsession

With a weight of almost 30% of the euro area economy and fiscal space, Germany holds the key to a revised policy mix. The German government’s budget surplus rose to 1.7% of GDP in 2018 and public debt has fallen rapidly to 60.9% of GDP at the end of 2018. In addition, the huge current account surplus points to insufficient domestic demand in Germany. This imbalance needs to be addressed urgently in line with the EU rules.

This can be done with an expansive fiscal policy. The German budget for 2019 is expansionary, with expenditure increases worth 0.5% of GDP and a reduction of the tax burden by 0.2% of GDP. In its stability programme, the German government expects the budget surplus to fall to 0.8% in 2019 and 2020 and to 0.5% in 2021-2023. However, since the preparation of the programme, it has lowered its expectations for economic growth. A small deficit becomes, therefore, increasingly likely. This puts at risk a fundamental premise of German fiscal policy: the schwarze Null must remain intact. That is to say, the budget must not end up in the red.

To insist on this if the economic situation remains weak would be a policy error. A few months ago, it was doubtful whether Germany itself needed more fiscal stimulus (see: KBC Economic Opinion European fiscal rules: Achilles tendon of the euro area). These doubts become less and less justified in light of the economic slowdown. The schwarze Null is considered necessary in view of the rising costs of ageing. But the best guarantee against the costs of ageing is strong economic support (see: KBC Economic Opinion Germany needs to become a little bit more Italian). To this end, the German economy also needs investment. Furthermore, considering inflationary developments in the eurozone, the risk of insufficient stimulation is greater than the risk of over-stimulation. The latter would fuel German inflation, which could accelerate the eurozone’s return to 2% inflation. It would remove an obstacle to the desirable normalisation of the ECB’s interest rate policy.

Meanwhile, the OECD reiterated the potential positive impact of fiscal stimulus in surplus countries. Maintaining a balanced budget in Germany would tip the scales negatively for not only Germany but the entire eurozone. However, structural reforms are needed in all countries so that everyone can continue to benefit from the stimulus policies in the long term. Otherwise, expansive policies in surplus countries only risk increasing economic divergence in the euro area.