Large valuation differences in EU housing markets

Read the publicatiion below or cllick here to open the PDF .

After Eurostat earlier published the Q1 2025 house price figures, the ECB in August also released its valuation metrics for housing markets in the 27 EU countries in that quarter. According to the average of the four metrics calculated by the central bank, price cooling in the EU housing market has reduced overvaluation from autumn 2022. But with price dynamics picking up again, overvaluation in the EU during the latest quarters rose again to 11% in Q1 2025. Large differences do remain between member states, both in terms of the level and course of valuation. In countries where the cooling turned into a sharp price correction (especially Luxembourg, Germany, Sweden and Austria), overvaluation fell sharply. In Luxembourg, overvaluation nevertheless remained high in Q1 2025, but fell below 10% in the three other countries mentioned. In countries that did not experience a cooling and where prices continued to rise strongly in recent years (especially Portugal, Greece, Spain, Croatia and Bulgaria), overvaluation in the housing market rose (sometimes sharply). In Belgium, where the cooling has remained relatively mild, overvaluation fell somewhat and averaged 9% across the four ECB metrics in Q1 2025. However, according to the valuation approach based on an econometric model (one of the ECB measures), the Belgian market is fairly correctly valued.

Valuation metrics ECB

The ECB calculates four measures of over- or undervaluation. Two of them concern the simple statistical price-to-income and price-to-rent ratios. The first involves relating the evolution of house prices to that of household income. The most recent value of that ratio is then compared with its long-term average, which is assumed to correspond to an equilibrium level. If the ratio rises too sharply above its long-term average, it is an indication that households' capacity to finance the purchase of a home is compromised and house prices have overshot. The second ratio relates the evolution of house prices to that of rents. In the longer term, the two should run in parallel. After all, when house prices rise more than rents, renting becomes relatively attractive, and vice versa. Again, the most recent value of the ratio is compared with its long-term average and a deviation indicates over- or undervaluation.

The other two valuation metrics are model-based. One takes the asset price approach and looks at the movement of the price-to-rent ratio relative to long-term interest rates. This involves benchmarking the return on a property investment (approximated by the inverse of the price-to-rent) against that of an alternative investment opportunity, specifically in a 10-year government bond. In the second modelling approach (hereafter referred to as 'econometric model'), house prices are regressed on household income, interest rates, population and housing stock. The extent to which the effective house price at a given point in time deviates from the equilibrium value estimated by the econometric regression (i.e. the error term in the regression equation) is taken as a measure of over- or undervaluation. The specification of the regression equation as well as the variables used do vary across EU countries and depend in part on data availability.

Large differences between EU countries

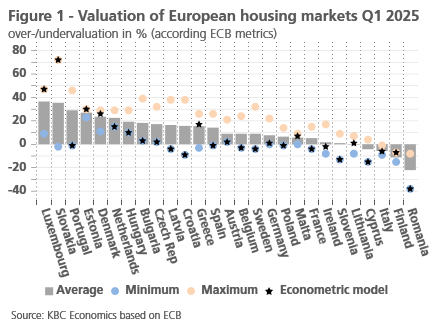

Figure 1 ranks the 27 EU countries by the state of their housing market, from most overvalued to most undervalued, as reflected in the average of the four ECB metrics. Of the four figures, the ECB publishes only the measure based on an econometric model. That one is the most comprehensive and is represented in Figure 1 by a black asterisk. Besides the average and the econometric model-based quantification, the ECB does publish the minimum and maximum of the four metrics, which correspond to the lowest and highest quantification respectively (the blue and pink dots in figure 1).

If we consider the average of the four ECB metrics, we find that in Q1 2025, the housing market was still overvalued by more than 10% in about half of the countries (i.e. 13 out of 27) (by more than 5% in 20 countries). This is striking, given the cooling trend in most housing markets from autumn 2022 onwards. The figure shows that there are large valuation differences between member states, though. Luxembourg (+37%) and Slovakia (+35%) are the two EU countries with the highest overvaluation in Q1 2025, while the housing market in Finland (-11%) and Romania (-22%) seems to be quite undervalued. Luxembourg and Finland stand out in particular. In both countries, the past cooling resulted in a solid house price correction, with more than 10% from peak to trough. In Luxembourg, this has not removed the overvaluation and the housing market remains expensively priced, while the Finnish market has now become cheap.

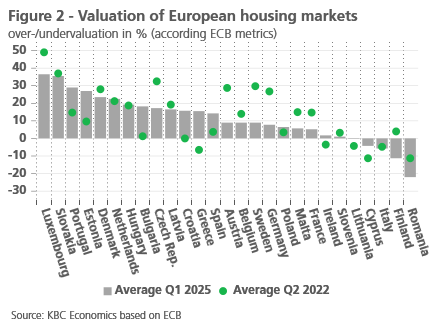

Figure 2 compares, for the average of the four ECB metrics, the most recent value (Q1 2025) with that just before the start of the cooling-off period (Q2 2022). In a number of countries with a strong cooling (even price correction), including especially Luxembourg, Germany, Sweden and Austria, overvaluation fell sharply. In other countries that did not experience a cooling and where prices continued to rise strongly (Portugal, Greece, Spain, Croatia and Bulgaria), housing market overvaluation rose sharply during the period under review. Country-specific factors sometimes played a role in this, such as increased investor interest in Bulgarian real estate due to the country's imminent accession to the eurozone. The ECB does not publish valuation figures for the EU housing market as a whole. An (unweighted) average of the 27 member states shows that the overvaluation across the EU (based on the average of the four metrics) fell from a peak of 12.4% in Q1 2022 to 8.1% in Q3 2023 due to the price cooling, but then rebounded to 11.2% in Q1 2025.

Another observation in figure 1 is that there are often large differences between the four ECB valuation approaches for most EU countries. This suggests that the over- or undervaluation data involve a lot of uncertainty and should therefore be interpreted with caution. Indeed, in Slovakia, Croatia, Latvia and Portugal, the difference between the highest (maximum) and lowest (minimum) valuation calculation is more than 40 percentage points. This difference is particularly large in Slovakia (74 percentage points). For quite a few countries, the valuation estimated by the econometric model corresponds to the lowest calculation (minimum). According to that most comprehensive valuation approach, the housing market would be overvalued by more than 10% in far fewer countries (only 6 out of 27).

Belgian housing market

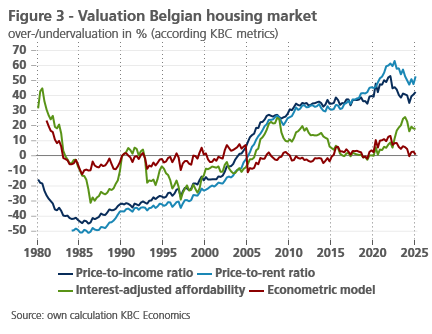

According to the average of the four ECB metrics, the Belgian housing market was still overvalued by 9% in Q1 2025. Just before the start of the cooling-off period (Q2 2022), which was relatively mild in Belgium, the overvaluation was 14%. However, according to the ECB econometric model, the Belgian market was slightly (by 3%) undervalued by early 2025. That finding is consistent with our own also econometric model-based valuation estimate. Similar to the ECB model, the KBC model establishes a long-term mathematical equilibrium link between house prices and their fundamentals. However, the KBC model looks over a longer period (1981-2025) and is also somewhat more sophisticated, as changes in property taxation over time are taken into account in addition to household income, mortgage interest rates and the number of households. As in the ECB model, the extent to which the effective price trend deviates from the equilibrium value calculated by the model (i.e. the error term in the regression equation) is seen as a measure of overvaluation. According to the KBC model, the Belgian market was close to equilibrium in Q1 2025 (an overvaluation of 0.8% only, see figure 3).

That the overvaluation has been (almost) eliminated implies that, at least from from the viewpoint of the econometric-model approach, a potential severe house price correction in Belgium should not be feared. However, this conclusion contrasts sharply with the fact that other measures, more specifically the classic price-to-income and price-to-rent ratios, do still point to a (solid) overvaluation (see the KBC quantification of these measures in figure 3). This is because those simple measures are less comprehensive and relate house price movements only to those of income and rent respectively. Moreover, the classical statistical valuation ratios suffer from the flaw that the result is very sensitive to the choice of period to calculate the long-term average against which the most recent value is plotted. In our own calculation, this is 1980/1984-2025, but should we only consider data since, say, 2000, the calculated overvaluation would be much lower. The ECB considers a much shorter period in its valuation calculation based on both ratios, which explains the lower values (see maximum for Belgium in figure 1).

More specifically, the statistical problem arises that the values of the two classical ratios do not oscillate around their mean (in technical jargon: they are not a 'stationary series'). As a result, their long-term average cannot pass as an equilibrium level. The problem does appear to be absent when we correct the price-to-income ratio by also taking mortgage interest rates into account. Indeed, the affordability of real estate depends not only on income but also on interest rates. The so-called 'interest-adjusted affordability measure' compares the annual annuity a mortgagee has to pay (both capital repayment and interest) with income per household (assumed term is 20 years at fixed interest). The more the annuity and income diverge, the more difficult it becomes to finance an owner-occupied home. As with the price-to-income ratio, this extended measure of affordability is expressed as percentage deviation from its long-term average. Due to the trend of sharp decline in interest rates, the overvaluation, calculated in this way, was completely eliminated in the pre-pandemic years. With the interest rate hike that followed since spring 2022, overvaluation rose again to 26% by the end of 2023, but the cooling of house price dynamics brought it down to 18% in Q1 2025 (figure 3).

Concluding remarks

Given the sometimes large differences between the various approaches, the interpretation of valuation figures should be treated with caution. This is why the ECB considers the average of its four metrics to estimate the valuation level of EU housing markets. Viewed this way, despite the cooling that has occurred in many countries, housing markets are still overvalued by more than 10% in about half of the member states. In countries where no cooling has occurred, overvaluation has even risen (sometimes sharply). This makes some vigilance, at least for some countries, still warranted. On the other hand, according to the broad approach based on an econometric model, the overvaluation problem affects fewer countries.

Although the average of the four ECB metrics in Belgium is still just under 10%, the Belgian housing market also no longer appears (significantly) overvalued based on the econometric modelling approach. Or in other words, housing prices are roughly in line with their fundamental determinants. It means that, from that angle, there would no longer be a substantial risk of price corrections. However, a neutral valuation level does not rule out a price correction: should one of the fundamental determinants deteriorate significantly (e.g. a negative income shock and sharply rising interest rates), house prices could still fall via that route. According to the KBC baseline scenario for those fundamentals, this is not the case and Belgian house prices are expected to rise by some 3% in both 2025 and 2026.