(Not) finding the house of your dreams

Insights on the mismatch between supply and demand on the Belgian housing market

A well-functioning housing market requires a good match between the supply of housing and the housing needs and desires of households. Imbalances between supply and demand on the housing market can involve both quantitative and qualitative mismatches and have potentially dire economic and social consequences. In this research report, we estimate the mismatches for the Belgian market. This is based on both hard figures and survey results. The analysis shows that, overall, the supply of housing in Belgium has adapted numerically well over the past decade to the increase in the number of households, and thus to the need for additional housing. Surveys on the dissatisfaction with the housing in which people live and the extent to which citizens have specific housing problems indicate that, from an EU perspective, the qualitative mismatch on the housing market in Belgium is also rather low. However, Belgium does have a relatively high proportion of under-occupied housing, which is suboptimal on a societal level in a context of land scarcity. This is largely explained by the fact that many older couples or singles continue to live in their oversized homes once the children have left home. The strong underutilisation is in line with Belgians' low relocation activity. This prevents a good flow that is important for a flexible housing market.

The research report also highlights important ongoing socio-demographic trends regarding household types and their housing behaviour and translates them into future housing needs. The combination of an aging population, a sharp increase in the number of people living alone, and the gradually more explicit choice of many households to live in an apartment have in recent years created a wave of "apartmentisation" of the housing stock in Belgium. A few simple and hypothetical simulations of the relative need for apartments versus houses until 2050 indicate a high probability that, from a demand perspective, this wave will continue strongly. From the supply side, it will then be necessary to respond in time to avoid future mismatches. Today, there are many frictions in government policy (strict regulations, strict requirements, long procedures, etc.) that stand in the way of a sufficiently flexible supply of new buildings. In addition to making new construction less inelastic, there is a need for measures that ensure more fluidity ('liquidity') in the existing housing market. The more people move, the more often houses will come on the market and the more likely it is that seeking households will find housing of their choice. Finally, more facilitation of changing interests towards new forms of housing (e.g., cohousing) is needed. Because these differ from traditional housing, interested parties still too often encounter inappropriate regulations and legal obstacles.

This research report consists of six sections. Section 1 discusses the economic and social importance of a well-functioning housing market with a supply of housing that matches the housing needs of households. The imbalance of supply and demand on the housing market manifests itself in quantitative and qualitative mismatches. The extent of the imbalance, however, is difficult to quantify precisely. In Sections 2 and 3, we estimate the existing quantitative and qualitative mismatch for the Belgian housing market, respectively. The analysis is based on both hard data and survey results and, where possible, places Belgium in an EU perspective. The aim is not to arrive at a precise numerical judgment, but to provide some insights and reflections on the matter. Section 4 discusses survey data on the (changing) housing behaviour of households. Understanding this is important for assessing (future) mismatches in the housing market. Section 5 looks ahead and focuses on the changing housing needs (quantity and type) in Belgium, and Flanders in particular, in the coming decades. In section 6, we formulate some concluding observations and policy recommendations.

1. A well-functioning housing market

A well-functioning housing market requires a good match between housing supply and demand. This requires not only that there be sufficient housing available for all households (absence of quantitative mismatch). The available housing must also match the housing preferences of households in terms of types and location as closely as possible (absence of qualitative mismatch). Often the housing market does not naturally move toward a desired balance. This occurs when the housing supply is inelastic and does not respond quickly enough to changes in demand (e.g., due to a shortage of building land or because of strict building regulations and zoning). An imbalance can also persist when many households struggle to find suitable housing. This may be because the housing available on the purchase or rental market is unaffordable for them, is not in the desired neighbourhood (e.g., too far from work, family or amenities) or does not have the desired characteristics or quality (e.g., too small or too large, not energy efficient).

When housing supply and demand are out of balance, there are potentially dire economic consequences that can lead to overall welfare losses. First, (both quantitative and qualitative) mismatches can lead to excessive price increases. These then affect the affordability of housing and increase the likelihood of a housing bubble. Ultimately, this can jeopardise financial stability and economic growth.1 Because living and working are strongly linked, mismatches in the housing market can more specifically give rise to mismatches in the labour market via poor housing mobility. Poor residential mobility combined with low willingness to commute then creates large regional differences in unemployment and employment rates. If commuting does occur (far), then poor residential mobility creates additional mobility costs and problems.

Apart from financial-economic effects, a malfunctioning housing market often has negative socioeconomic consequences. For example, in the absence of suitable and affordable housing, young adults may delay leaving the parental home. For young partners considering family expansion or gradually earning a higher income, it is important that they have opportunities to move into better quality housing (move up the "housing ladder"). The role of the housing situation is also often crucial when partners divorce or for couples whose children have left home. In flexible housing markets, they move more often and more quickly into a new, adapted home. More generally, the existence of increasingly complex, pluralistic forms of cohabitation requires greater flexibility and diversity in the housing supply. Finally, adapted and quality housing ensures the physical health and psychological well-being of citizens.

2. Quantitative mismatch in the housing market

Whether there is a numerical shortage of housing units is not easy to determine in practice. For Belgium, there are figures on the number of households and the number of housing units available to them, but the statistical data do not allow a good link between the two. Moreover, the number of households is an indicator of total housing need, which does not correspond to what they wish to buy or rent on the market at any given time (the effective housing demand). Similarly, the existing housing stock does not correspond to what is offered for sale or rent in the market at any given time (the effective supply). Nevertheless, the relationship between the number of housing units and the number of households is often seen as a measure of the mismatch between prevailing demand and supply in the housing market.

Ratio of housing units to households

Figure 1 shows the number of housing units per 1,000 households in Belgium over the past three decades. It is striking that the ratio was well above 1,000 throughout the period. At first glance, this suggests that there would be a continuous large oversupply of housing units. For example, in 2023 there were over 600,000 more housing units than households in Belgium. Since there is no one-to-one relationship between housing and households, this conclusion should not be drawn lightly. First of all, households are increasingly pluriform and thus difficult to define residentially (e.g., several single people deliberately living together in one dwelling, elderly people moving in with caretakers, households with more than one dwelling because one of the partners works elsewhere and stays there during the week). Furthermore, housing unit figures also include second homes, homes in vacation parks or for short-term rental, (certain) student and hotel rooms and the like.2 Measurement problems, incomplete or erroneous registration and specific situations (vacant and uninhabitable dwellings, dwellings used for non-residential functions such as storage, dwellings occupied by migrant workers, the homeless, living in caravans, houseboats, etc.) also distort the numerical relationship between housing units and households.

Still, to get some indication of any distortion in the housing market, one can look at the evolution (rather than the level) of the ratio of housing units to households. When the number of households increases much more than the number of housing units, this may indicate (impending) housing shortages, and vice versa. It is notable that the number of available housing units has increased more than the number of households over the past decade. This contrasts sharply with the situation at the beginning of this century, when the reverse occurred. The reversal of the ratio indicates that the supply of housing in Belgium, at least in terms of volume, has, since 2012, generally adapted well to demographic trends, and thus to the need for additional housing.

A quick indicator of possible quantitative mismatches are sharply rising housing prices. In the early 2000s, the decline in the ratio of housing units to households was accompanied by sharp annual price increases (see Figure 1). Prior to the 2007-2009 financial crisis, these even peaked to well above 10%. Subsequent increases in the ratio tempered price pressures. More recently, the ratio of housing units to households appears to be stabilising. This reflects stronger demand for housing in the until recently ultra-low interest rate environment. Until the recent cooling of the housing market caused by the interest rate shock, this was accompanied by again stronger price dynamics.

The increase in the ratio of housing units to households since 2012 is also partly explained by the increased number of non-principal residences, including second homes and student rooms. Precise figures on this are not available. Thus, as already indicated, we should be wary of drawing strong conclusions regarding housing market imbalances. Indeed, despite the general increase in the ratio of housing units to households, there are indications that the housing shortage in Belgium persists locally (e.g., in certain cities such as Ghent and Leuven) and in specific segments of the housing market (waiting lists for social rents, private rental market, etc.). On the other hand, the increase in the ratio may also imply that an oversupply of housing may be developing in certain locations.

Regional perspective

Figure 2 shows the ratio of housing units to households for the three Belgian regions. In Flanders, the level of the ratio is relatively high, largely explained by the fact that there are many second homes there (mainly on the coast). In Wallonia, the adjustment of housing supply to the increase in the number of households over the past decade has been relatively stronger than in Flanders. This may be due to a smoother granting of building permits (there is still more open space in the region). In Brussels, the ratio has followed a different course in recent decades: between 2007 and 2012 it fell sharply. Although the ratio subsequently increased in Brussels, this did not compensate for the previous trend. Moreover, the ratio has reversed again very recently. .

The fact that the supply of housing in Wallonia has adapted better to demand over the past decade than elsewhere resulted in a smaller rise in house prices in that region. The median sales price rose by 13 and 8 percentage points less than in Flanders and Brussels, respectively, between 2010 (the year in which Statbel switched from an average to a median price in its reporting) and 2023 (see Figure 3).

3. Qualitative mismatch in the housing market

Even more than for the quantitative mismatch, it is difficult to determine to what extent the available housing stock matches prevailing housing preferences. This possible qualitative mismatch can be viewed from two perspectives. From the perspective of individual households, there is the question of whether their own housing preferences are effectively met. This concerns a rather subjective, personal perception about the degree to which one is or is not satisfied with the housing in which one lives or which is offered on the market. Also, the extent to which people indicate that they struggle with specific housing problems (e.g., affordability) may indicate an unbalanced market.

The reporting of a subjective satisfaction with one's housing situation by a fairly large number of households may nevertheless imply a suboptimal situation of the (future) housing market at the societal level. This can be the case, for example, when many couples continue to live in an oversized home after their children have left home. This then contributes to a large underutilisation of the housing stock, which is pernicious in a context of land scarcity. So we also need to look at the potential qualitative mismatch more broadly as a social problem and include more objective measures in the analysis (e.g. degree of over- or under-utilisation of the housing stock).

Subjective assessment of housing situation

To form an idea about the qualitative mismatch on the Belgian housing market, we use figures published by Eurostat. Figure 4 shows the results of a survey, conducted in 2012 and 2023, which polled the population on their level of satisfaction with the housing in which they live. Four responses are possible: very satisfied, quite satisfied, not very satisfied and not at all satisfied. The sum of the last two answers can then be seen as an indicator of qualitative mismatch. In other words, not being satisfied implies that the housing characteristics (type, quality, location, etc.) do not match the housing preference. The figures show that, compared to other EU countries, the level of housing dissatisfaction in Belgium is rather low (5.6% of respondents compared to 10% in the EU). Moreover, it has declined over the past decade. This suggests that, viewed this way, the qualitative mismatch overall would be rather low. Figure 5 shows dissatisfaction by age for Belgium and the EU. It is highest for 25–34-year-olds and then declines as higher ages are considered. Thus, with younger generations leaving the parental home and/or starting a family, housing dissatisfaction appears to peak.

Another recent Eurostat survey, conducted in 2023, gauges the extent to which people face specific housing problems at the time of survey (for financial reasons, because of family or personal circumstances, for health reasons, because of work situation, or because of end of lease). A high percentage may indicate a difficult transition to a new, more adapted home and thus an unbalanced market. Figure 6 shows that, at 3.7% of respondents, housing problems in Belgium are rather low (the EU figure is 6.3%). When broken down by cause, compared to the EU as a whole, money and work appear to cause relatively fewer housing problems in Belgium, but family or personal situations cause relatively more (Figure 7).

Over- and under-occupancy in the housing market

Yet another way to estimate the qualitative mismatch is to look at the extent to which there is over- or under-occupation of existing housing. Again, we rely on Eurostat figures, this time concerning the overcrowding rate on the one hand and the proportion of people living in an under-occupied dwelling on the other. The first measure reflects the proportion of the population living in a dwelling that does not have a minimum number of rooms (according to the nature and size of the household).[1] The second measure is opposite to the first and reflects the proportion of the population living in a dwelling that has more than the minimum required number of rooms (again, according to the nature and size of the household living in it). Both measures give an indication of the degree of distortion between the existing housing stock and the types of households present.

Figure 8 shows the evolution of the degree of overcrowding for Belgium and the EU. Belgium again scores relatively well, with a relatively low overcrowding problem. Only in the Netherlands, Ireland, Malta and Cyprus is the indicator lower than in Belgium. It is noteworthy, however, that the rate has increased in Belgium since 2015, while it continued to decline across the EU. Often overcrowding is related to low income and poverty and thus the manifestation of an affordability problem.

Figure 9 shows, again for Belgium and the EU, the proportion of people living in under-occupied housing. At almost 60%, that figure is almost double the EU average of 33%. It is higher in only a limited number of countries (the same as listed for the other indicator). The fact that housing in Belgium is among the most under-occupied in Europe is largely explained by the fact that many older couples or singles still continue to live in their (too large) home after their children have left the parental home ("empty nest" phase). However, that number has declined since 2015, although the decline seems to have stopped in recent years (see Figure 9). That the overall rate of under-occupation remains relatively high may also have to do with the large and increasing complexity of households in Belgium. For example, the break-up of families results in living apart, which then often also implies housing that is too large.

Moving mobility

The high level of under-occupancy is in line with Belgians' low relocation activity. A 2012 Eurostat survey (more recent figures are not available) shows that Belgium's propensity to move is rather mediocre in an EU perspective. In a flexible housing market, households regularly re-evaluate their housing situation and move house in response to changing family situations and through different stages of life. The more people move, the more often housing comes on the market and the more likely it is that seeking households will find housing of their choice. In other words, high mobility and good flow in the housing market reduce the likelihood of mismatches. In Belgium, according to Statbel figures, annual housing moves have remained rather stable over the past two decades at around 10% of the population (of which 4 to 5% within the same municipality and 5 to 6% between municipalities).

The question remains to what extent the rather limited mobility to move in Belgium is the cause or consequence of an insufficiently flexible housing market. It is notable that moving activity is not increasing in a context of frequent socio-demographic changes. Examples of the latter are: the increased level of education (highly educated people move more often and further), the ageing of the population (elderly people moving to nursing homes), the increasing complexity and instability of forms of cohabitation (the break-up of families and the emergence of newly-constituted households go hand in hand with a move). Part of the paradox may be explained by the fact that the impact of these changes themselves is not always clear. For example, older people are generally less mobile than younger people, so the ageing of the population may reduce rather than increase the total number of moves.

4. Living behaviour according to survey data

Understanding how socio-demographic trends affect housing is important for estimating (future) housing market mismatches. In this section, we discuss survey data on households' housing behaviour. This housing behaviour concerns the choice of housing type (either a house or an apartment) that households (by type and age) effectively make. This individual behaviour combined with the numbers of diverse household types then reflects the housing needs for the whole of the households. Note that the survey data on housing behaviour express an existing state and may not fully reflect the ideal housing desire of the affected households. Thus, they may implicitly imply some qualitative mismatch.

Apartmentisation of housing stock

An important socio-demographic trend in Belgium concerns the ever-increasing absolute number as well as larger share of single persons ("one-person households") within the total number of households. This requires not only a greater demand for housing, but also for smaller housing units. From Statbel's Census data (which every 10 years surveys population characteristics including housing), we know that single people are more likely to live in apartments (figure 10). This is especially true among young people, but also among singles in the older age groups. Couples with children are least likely to live in apartments, and single parents slightly more likely than couples without children.

At higher ages, households of all types move more into apartments, although the age from when this happens does differ between types. Especially couples without children appear to live relatively more in an apartment from the age of 55. These are mostly couples whose children have left the parental home and who move to a more central, comfortable and compact home (often a newly built apartment in residential areas). They are looking for a home more suited to their size and are therefore called the "slimfit generation" by real estate economist Frank Vastmans (KU Leuven). Although the proportion of older people who belong to this group is increasing, the majority nevertheless still continue to live in a (too large, often detached) house (sometimes called “empty-nesters”).

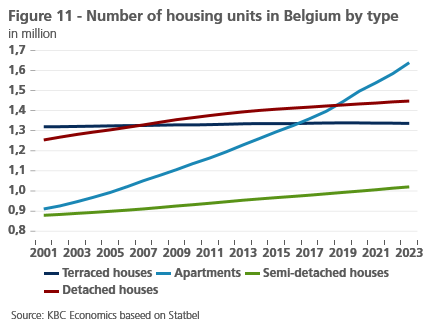

The combination of an ageing population, a greatly increased proportion of single people and the changing housing behaviour of the "slimfit generation" has had a major effect on the Belgian housing market in recent years. It has created a wave of “apartmentisation” of the housing stock (see figure 11) and thus contributed to reducing the underutilisation of available housing (although it remains relatively high, see figure 9). To the extent that this has brought (larger) houses onto the market for young families with children, who also renovate relatively more than those over 654, it has further reduced the qualitative mismatch on the housing market.

No figures are publicly available on the Statbel website for the latest 2021 Census on how different household types live in Belgium (the figures shown in figure 10 refer to the earlier 2011 Census).5 However, there are more recent 2018 figures on this for Flanders in the periodic Housing Survey conducted by the Flemish Housing Agency.6 Figure 12 shows the share of the various household types living in a "multi-family dwelling" (i.e. more than one dwelling unit per plot) in Flanders at the time of the 2005 and 2018 surveys. In practice, these are mainly apartments (in the figure and in what follows we therefore use that term for simplicity), but it also includes studios, student rooms, service flats, housing in residential care centres, etc. The apartmentisation discussed earlier is also reflected here in the figures on housing behaviour (mainly that of singles).

Linking the Housing Surveys with "hard" figures on the numbers of various household types in Flanders (source: Federal Planning Bureau) can be compared with "hard" figures on the effectively available numbers of apartments versus houses (source: Statbel). For example, in 2005 the effective number of apartments in Flanders was almost 60,000 units higher than calculated based on the Housing Survey and the number of households. By 2018, that had risen to over 110,000 units. The increase in the figures between 2005 and 2018 may be largely related to the increased number of second homes. It can be inferred from the figures that three quarters of the increase in the effective number of apartments in Flanders between 2005 and 2018 can be explained by the changed household composition combined with the changed living behaviour of households. The remaining small quarter then concerns second homes, student rooms, etc.

5. Future perspective housing demand

Demographic outlook on household types

According to the demographic forecasts of the Federal Planning Bureau (FPB), the number of one-person households (singles) in particular will continue to increase significantly in the coming decades (figure 13). At the beginning of the 1990s, their share of all households in Belgium was less than 30%. In 2023 it was 36% and is expected to reach 40% by 2050. This development will further fuel the trend of living smaller but will also require more homes in terms of numbers compared to a situation where citizens would live together more. In addition, the FPB projections show that more stable, traditional relationships (especially married couples with children) will continue to give way to other, often more pluralistic forms of cohabitation. The latter tend to be accompanied by greater instability, which will require greater flexibility in housing supply.

It is impossible to make a precise estimate of future housing needs on the basis of FPB household projections alone. Indeed, not only future changes in the various household types, but also which age group they are in and how their housing behaviour continues to change over time will determine future housing needs. FPB projections of household types are not available by age categories, making a cohort approach impossible. An additional problem is that the FPB household outlook in fact implicitly already contains certain assumptions about housing supply. After all, with a two-way influence, the available supply also steers the household evolution.7

Simulation of housing demand for apartments and houses

Despite imperfect data and technical difficulties, we can give a rough indication of future housing needs by linking FPB projections on the number of various household types to survey figures on housing for the household types. Regarding the latter, however, we must then make an assumption about how housing behaviour will continue to evolve. The exercise is thus more of a simulation under assumptions (e.g., holding housing behaviour constant or continuing the ongoing trend). This non-fine quantification gives only a rough indication of the overall numerical need for housing in the coming decades, as well as in what proportion apartments versus houses will be needed. To the extent that this cannot be met (sufficiently quickly) from the supply, mismatches then arise.8 Note: as already indicated, the survey figures on housing behaviour may not reflect the ideal housing desire of the households involved. Their use in our quantification may thus also still include qualitative mismatches.

To work out how many additional housing units (apartments and houses combined) will be needed in the coming decades, we can simply look at the household growth rate predicted by the FPB. This assumes a one-to-one relationship between housing units and households and makes abstraction of the number of dwellings without domicile (second homes, student rooms...). Figure 14 shows the growth of the number of housing units thus estimated needed in the three Belgian regions as of 2024 (the series was indexed with 2024 equal to 100). Growth is stronger in Flanders than in Wallonia. Between today and 2050, the two regions will need about 430,000 and 140,000 additional housing units, respectively, in absolute terms. In Brussels, there is initially a relatively small increase and by 2050 housing needs even fall back to current levels. An important explanation for the regional differences concerns the relatively strong increase in the number of single persons expected by the FPB in Flanders, in turn partly explained by the stronger ageing of the population in the region. Given the already much higher population density and only scarce space left to build, the relatively stronger expansion of housing needs in Flanders will pose a greater challenge than in Wallonia.

We simulate how many apartments or houses will be needed in the coming decades only for Flanders. Indeed, for that region, we have a fairly recent picture of the housing behaviour of different types of households with the Housing Survey 2018. A first simulation assumes a housing behaviour that has remained unchanged since that survey. In this (rather unlikely) scenario, there is only the impact on the relative number of apartments versus houses of the changing numbers of household types as predicted by the FPB. Especially the further strong increase in the number of one-person households, combined with the already relatively high percentage of them living in an apartment (48%) in the Housing Survey 2018, ensures that the additional housing need in Flanders in the coming decades, relatively speaking, will have to be filled more and more with apartments (see figure 15).

The first simulation probably underestimates the actual need for apartments. Since the 2018 Housing Survey, the trend of apartment living has continued, especially among single-person households, but probably in other household types as well.9 It is likely that this will continue to be the case in the coming years, although the extent remains uncertain given, as indicated above, the unclear impact of socio-demographic trends. A second simulation assumes (purely hypothetically) that apartmentisation in the housing behaviour of various household types will continue in the coming decades but at a slower pace. Specifically, we assume that the share of each of the household types living in an apartment continues to increase annually through 2050 at half the average annual increase between 2005 and 2018. For the large group of single-parent households, this means, for example, that the share of apartment dwellers increases from 48% in 2018 (Housing Survey 2018) to 59% in 2050. Only among single-parent households was there no increase in the share of apartment dwellers between the 2015 Housing Survey and the 2018 one (even a slight decrease, see figure 12) and we simply keep the share unchanged at the 2018 figure.

The second simulation, which is purely illustrative, shows that even slowing changing behaviour toward apartment living implies a heavy impact on the relative need for apartments versus houses (see figure 15). In particular, a further increasing absolute number of single people, combined with the fact that that group would be even more likely to live in an apartment, drives that need. According to the second simulation, between 2024 and 2050 there would be a need in absolute terms for some 330,000 additional apartments in Flanders, compared to a rounded 65,000 additional houses.10 Note that, apart from the hypothetical character, the simulations abstract from the possibly also changing needs for other housing (second homes, vacation homes, student rooms...).

Difficult exercise

The simulations in section 5 concern a rather static analysis that does not take into account dynamic cohort and age effects on changes in household types and their housing behaviour. Although very crude, they nevertheless illustrate that, from a supply perspective, apartmentisation should continue in the coming decades. Nevertheless, the extent of this remains uncertain and depends on the further housing behaviour of different household types. Incidentally, in our analysis there also remains an inherent uncertainty regarding the extent to which the included figures on housing behaviour effectively correspond to the ideal housing desire. It is not because one lives in a certain way that this is also preferred by the households in question.

The conclusion is that it remains extremely difficult to respond to future housing needs and desires in a timely manner from the supply side, especially since there are also differences by location (e.g., urban versus rural). Dynamic modelling based on more and better detail on changes in housing and moving behaviour is needed and can point to specific needs. For example, in the coming years there will be an increasing demand from the growing group of elderly singles not so much for classic apartments but rather for care real estate aimed at the elderly. After all, the further ageing of the population also implies an increase in the number of very old people (over 80), both in absolute terms and in terms of the proportion of people over 65. Within that group, there are many single people (mostly women because their life expectancy is higher). We know that this group prefers to remain in their (oversized) homes for as long as possible, and, when no longer possible, to move into nursing homes (assisted living facilities).

Role of the government

Apart from providing better figures and analyses to estimate future housing demand (e.g., the FPB could play a greater role in this), the government can also take concrete measures to improve the smooth functioning of the housing market. One of the goals here should be to improve the flow on the market. This increases liquidity in the housing market and therefore ensures better and faster matching of supply to demand. This directly improves housing satisfaction and, in addition, reduces the sacrifice of free space for new housing, accelerates the sustainability of the housing stock (the moment of purchase is often also the moment when investments are made to make the house more sustainable) and reduces the mismatch on the labour market. Steps have already been taken in reducing transaction costs (registration fees) when purchasing a home, but more is possible. For example, the Netherlands has been successfully experimenting for some time with "relocation coaches," who guide potential buyers or renters in their desire to live more appropriately. Paying attention to a healthy mix and transition between homeownership, private renting and social renting also promotes through-flow.

Another important goal is for the new construction supply to be sufficiently flexible to meet prevailing demand. Today there are a lot of frictions in construction that stand in the way of this flexibility (strict regulations, stringent requirements, long procedures, etc.). They create an inelastic supply and often make new construction or renovation so expensive and complex that they become unfeasible for many. In Belgium today, many homes still do not meet (future) housing needs. Demolition and renovation is often the better solution, not only from an energy point of view but also because it is usually associated with higher densities (on average, a demolished home is replaced by 2.2 new housing units, source: Embuild).

Furthermore, the government can also play a more facilitating role with regard to changing interests in new forms of housing that deviate from traditional housing (cohousing, kangaroo living, cooperative living, renting with the option to buy, mobile care units, tiny houses, etc.). The realisation of such housing projects (which often boil down to shared ownership) is not always easy because initiators still too often come up against inappropriate regulations and legal obstacles. The same applies to so-called "adaptive construction", which implies the possibility to quickly make structural adjustments to dwellings in the case of new residents or a changed situation of existing residents.

1 See, e.g., Reusens, P. and Warisse Ch. (2018), "Housing prices and economic growth in Belgium," Economic Review NBB..

2 Many of them are homes without a domicile. In Flanders, this type of housing increased from 9% of the housing stock at the beginning of the 1990s to 13% in 2021 (source: Statistics Flanders).

3 Overcrowding occurs when the household does not have a minimum number of rooms equal to: 1 room for the household; 1 room per couple in the household; 1 room per single person aged 18 years or older; 1 room per couple of same-sex singles between the ages of 12 and 17.

4 See Van den Broeck K. (2019), "Barriers to renovation on the demand side," Steunpunt Wonen, Leuven.

5 Statbel only provides figures on the numbers of different household types and housing types separately, not the combined numbers.

6 The first results of the new Housing Survey 2023 will not be available until the fall of 2024..

7 On the issue of estimating future housing demand, see also, e.g., Vastmans, F. and Dreesen, S. (2021), "Predicting regional housing demand: what approaches are possible?", Steunpunt Wonen, Leuven.

8 In our simple exercise, we do not include potential housing supply (available lots or space). For an analysis that does, see Flemish Environmental Planning Agency (Department of the Environment, 2023), "Where will the Fleming live in 2035? A modelling of housing demand by well-located residential areas".

9 According to the Statbel figures (which, as already indicated, are heavily distorted by the increased number of second homes, student rooms, etc.), the total number of apartments and houses in Flanders increased by 147,000 and 41,000, respectively, between 2018 and 2023.

10 The small difference between the sum of the two figures and the total additional housing need in Flanders mentioned earlier (430,000) is explained by the fact that the FPB forecast regarding the residual category "other private household types" is not included here due to no figures in the Housing Survey.