Economic Perspectives May 2020

Read the full publication below or click here to open the PDF.

- The magnitude of the economic shock of the coronavirus crisis is becoming clearer as Q1 GDP data revealed that the euro area, US and Chinese economies all contracted sharply at the beginning of the year. We continue to expect severe recessions in most countries this year followed by strong recoveries in 2021. In particular, for Q2 we expect a major economic decline in the western economies. However, given the fact that many countries have already begun a gradual process of lifting lockdown measures and reopening their economies, the risk of an even more adverse outcome has increased, particularly if a renewed wave of Covid-19 prompts the need for a renewed lockdown.

- In the euro area, the earlier than expected lifting of lockdowns could mean that the trough of the recession will be slightly less deep than previously anticipated. At the same time, however, several factors related to business investment, the labour market, private consumption and international trade suggest that the recovery thereafter will be less robust. We therefore expect a weaker recovery in 2021 than previously envisaged and find that it will take longer for euro area GDP to recover to its pre-crisis level.

- In the US, many states are reopening even though there has not yet been a steady decline in new Covid-19 cases or deaths. The risk that the US may need to re-impose lockdowns in the near future has therefore clearly grown. Furthermore, the very severe impact on the US labour market, with unemployment jumping to 14%, suggests that the recovery in the US may also be quite gradual.

- Financial market turbulence appears to have eased since late March in tandem with the significant policy responses taken by the Fed and the ECB. However, intra-EMU spreads still remain elevated, reflecting uncertainty related to European solidarity which has been stoked by the recent German court ruling on ECB asset purchases. Such concerns will likely keep spreads elevated and weigh on the euro versus the US dollar in the short term. Smaller central banks have stepped up their monetary stimulus too. The Czech National Bank lowered the deposit rate further in May 2020, from 1% to 0.25%.

- The global oil market has seen a severe impact from the coronavirus crisis with oil prices collapsing to multi-year lows. In the past two weeks, the oil market has witnessed some signs of stabilisation, but it is not out of the woods yet, as the supply overhang remains unprecedented. The current record dislocation between oil demand and supply may be partly curbed by a new OPEC+ deal to cut production by 10% of global supplies starting in May, but a true market rebalancing requires a meaningful recovery in demand.

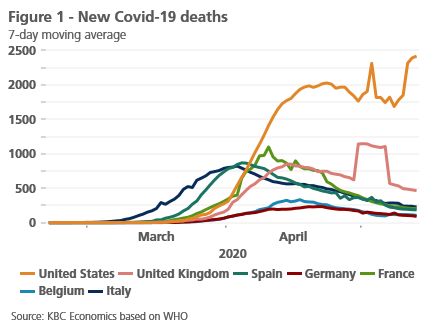

The coronavirus crisis and its economic fallout remains the main theme driving developments around the world. A major health crisis and human tragedy, the spread of the Covid-19 virus is also causing severe disruptions to the global economy and its outlook. Fortunately, many European countries appear to be over the peak in terms of the number of new cases or new deaths caused by the virus, with these figures steadily declining. The same can’t yet be said of the United States, with daily new deaths not yet clearly falling (figure 1).

Our global economic outlook remains roughly the same, with severe recessions in most countries this year followed by strong recoveries in 2021. We also still expect to see depressed oil prices in the short term given the unprecedented supply glut driven by the collapse in oil demand (see Box 1). However, two important developments since the release of our last Economic Perspectives have led us to fine-tune our outlook, which is still subject to considerable uncertainty. First, additional economic data has been released which give us some sense of the magnitude of the initial economic disruption from the coronavirus crisis, including Q1 GDP figures in many countries. Second, a number of countries have begun a gradual process of lifting lockdown measures and reopening their economies.

Box 1 - Oil market hammered by an unprecedented supply glut

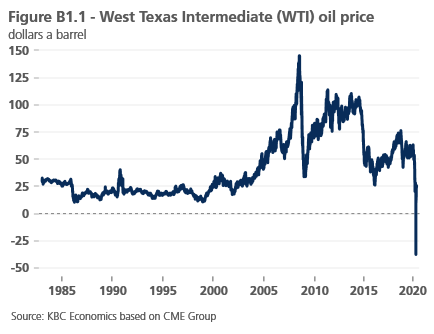

The global oil market has been crushed by the Covid-19 pandemic, with oil prices collapsing to multi-year lows. The US crude oil benchmark, West Texas Intermediate (WTI), was hit particularly hard in mid-April when, for the first time in history, futures prices plunged into negative territory (figure B1.1). Technical factors, such as a liquidity shortage ahead of the May contract expiry, played a part, but the price crash ultimately reflected underlying physical market weakness.

Since WTI is a physically settled oil benchmark, i.e. requiring a physical delivery in Cushing, Oklahoma at contract expiry, there is a direct link between the futures market, the so-called paper market, and the physical market, also known as the wet market. Hence, with the physical market being massively oversupplied and storage capacities in Cushing effectively booked out, traders who lacked the storage space were essentially willing to pay others to take oil off their hands, causing oil prices to fall as low as -40 dollars a barrel.

Meanwhile, Brent crude, the international oil benchmark, has also witnessed severe downward pressures and dropped to its lowest level since 1999 but has avoided negative prices. There are at least two good reasons why Brent is, in our view, less likely to experience the same episode as WTI in mid-April. First, unlike the US benchmark, Brent crude is cash-settled, meaning that no physical cargo of crude is taken when the contract expires, thus alleviating the immediate pressures on the storage facilities. Second, whereas WTI is land-locked, Brent is a seaborne crude, meaning that traders can use (super)tankers and effectively be less affected by storage constraints.

In the past two weeks, the oil market has witnessedsome signs of stabilisation; however, it is not out of the woods yet. The supply overhang remains unprecedented, largely owing to the collapse of oil demand triggered by world-wide containment measures to mitigate the spread of the coronavirus. In April, the drop in oil demand was estimated between 25-30 million barrels per day, more than a quarter of global oil consumption. Such a historic dislocation between oil demand and supply is expected to be partly reduced by the new OPEC+ deal to cut production by 9.7 million barrels per day, or around 10% of global supplies, starting in May.

The record output curbs should help to prevent global oil storage from maxing out within the coming weeks; however, they fall short of triggering a meaningful rebalancing of market fundamentals. To shift the oversupplied market to a deficit, the recovery of oil demand is critical, which in turn remains contingent on easing lockdown measures across the globe. That is to say, unless demand recovers, oil prices are set to remain volatile and depressed at relatively low levels.

Given the enormous uncertainty currently present in the global landscape, we continue to work with multiple scenarios to which we assign different probabilities. Specifically, in addition to our base scenario, we also outline a more optimistic scenario and a more pessimistic scenario. Given recent developments, we have slightly adjusted the probabilities we assign each scenario as well as their definitions. In the optimistic scenario, a shorter lockdown period leads to a swift economic bounce-back as businesses reopen, employees quickly get hired back (if fired) or return to their job (if temporarily unemployed), and consumer spending picks back up. In such a scenario, however, new breakthroughs in treatments or testing that help lessen the threat of the virus would likely be necessary in order to see this kind of rebound. While this is still a possibility, we view it as rather unlikely, and still assign only a 15% probability to the optimistic scenario.

In the base scenario, the lockdowns are gradually lifted from mid-Q2 on, as we see happening now, but the immediate economic damage is larger, and the economic recovery is somewhat slower. Consumers may be more reluctant to return to shops even if the lockdowns are lifted, businesses will likely be more cautious about investment decisions, and the rehiring of temporarily unemployed workers may not be perfectly smooth. Furthermore, in most cases the lifting of lockdowns is done in tandem with continued social distancing measures, meaning we won’t see an automatic return to business as usual. Moreover, international trade is likely to be disturbed by ongoing shipping problems, supply complications and restrictions on mobility. We assign a 45% probability to the base scenario, down from 50% last month, as we now see an increased likelihood that we are moving towards the pessimistic scenario.

In the pessimistic scenario, the virus remains an ongoing threat as new waves surface and health care systems remain under excessive pressure until a vaccine is found and widely distributed. This means that we would expect to see on-off lockdown periods going forward, which would lead to longer-term stagnation and would delay any recovery. We assign a 40% probability to this scenario compared to 35% last month. Indeed, some countries around the world are already starting to see second waves of the virus (see Box 2).

Box 2 - The Japanese experience with a second Covid-19 infection wave

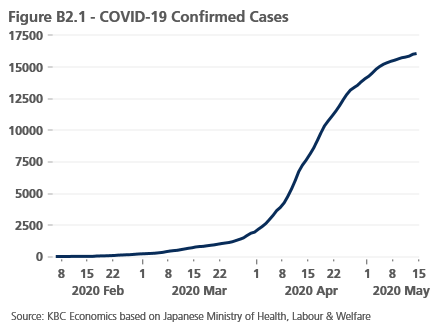

The Japanese experience with Covid-19 has involved two waves of infections. It illustrates the serious risks that the rest of the world also faces after the first wave of infections has moderated in many countries thanks to far-reaching lockdown measures.

According to the Japanese National Institute of Infectious Diseases (NIID), the first wave of infections in Japan originated from travellers and people returning from China and East Asia in January 2020, with the first reported case dating from 16 January. There was also a Covid-19 outbreak on the Diamond Princess cruise ship, which was quarantined on 5 February. After causing some local clusters of infections, this first wave of the pandemic largely disappeared by early March.

There has since been, however, a second wave of infections, dating back to the period between 11 and 23 March, this time originating from travellers coming back to Japan from the US and Europe. There appear to have been three fundamental factors that facilitated this second wave. First, the border closure after the first wave was only selective, leaving open the possibility for the re-entry of the pandemic from other countries and regions. Second, for a long period, policymakers were relatively reluctant to impose very stringent measures in order not to cause too much damage in economic terms. This may have gone hand in hand with an underestimation of the strain Covid-19 would pose on the Japanese health system. Third, in the specific Japanese legal context, it is difficult to impose strict pre-emptive and compulsory measures on citizens that are not diagnosed as Covid-19 positive.

The second wave has been much more serious than the first one. It required the government to declare a state of emergency on 7 April, which has been extended several times, and is currently scheduled to be in place until 31 May. Given the specific legal and constitutional situation in Japan, this state of emergency cannot include a general ‘lockdown’ of the population. However, beside recommendations of social distancing and the suspension of events that risk spreading the virus, all patients tested positive can be ordered to be hospitalised.

As a result of a substantial number of policy measures, including the closure of the border to a large number of countries, the second wave of infections now appears to be over its peak. As of 11 May, Japan has reported 15,798 confirmed Covid-19 cases and 621 deaths. The number of confirmed infec-tion cases appears near its peak (figure B2.1), while the number of hospitalised patients needing a ven-tilator or in intensive care has been falling again since early May.

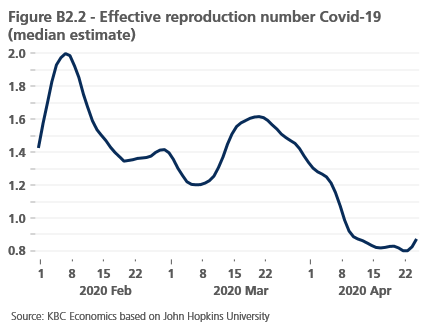

Perhaps most importantly, the repro-duction number of the virus dropped below 1 in April (figure B2.2), indicating that the pandemic will gradually fade out under the current policy measures. A latest slight uptick of the reproduction number, however, signals that caution is still needed in order to avoid a third wave of infections. In that con-text, the planned Olympics in July 2020 have been cancelled.

A disastrous Q1 for Europe

Preliminary Q1 growth figures for several euro area countries confirm that the coronavirus crisis is having an unprecedented and sharp impact on the European economy. Euro area real GDP fell 3.8% qoq in Q1, with most of that weakness coming only at the very end of the quarter, as major lockdowns started around mid-March. This figure is worse than expected and signals that the coronavirus crisis hit the European economy hard at an early stage. This could be explained by more substantial negative international spillovers, in particular due to distortions in global value chains after the virus outbreak in China. Alternatively, the sudden stop of the European economy may have led to a more dramatic fallback in economic activity. Although the Q1 GDP estimates for European countries are subject to considerable uncertainty, and we therefore may see more sizable than normal revisions in the future, the figures make clear that some countries faced a more severe impact than others. France, for example, which normally generates a relatively high proportion of its GDP from services, saw a much steeper decline compared to Germany (as suggested by the euro area figure), which generally derives more of its GDP from the industrial sector. This is consistent with signals from business surveys which suggest that service sectors have been much harder hit by the coronavirus crisis.

These business surveys, as well as other monthly indicators such as consumer confidence, continue to point to ongoing weakness in the second quarter. The manufacturing sector PMI for the euro area, for example, fell further to 33.4 in April from 44.5 in March and 49.2 in February (where above 50 indicates expansion). As mentioned, the services sector has fared even worse, with the services PMI for the euro area falling to a dismal low of 12 in April, down from 26.4 in March and 52.6 in February. Temporary unemployment has jumped in a number of countries as well, and while these numbers aren’t fully reflected in the official unemployment statistics, the coronavirus crisis is clearly weighing very heavily on the labour market. The rise in unemployment and the related rise in job insecurity will slow down the recovery.

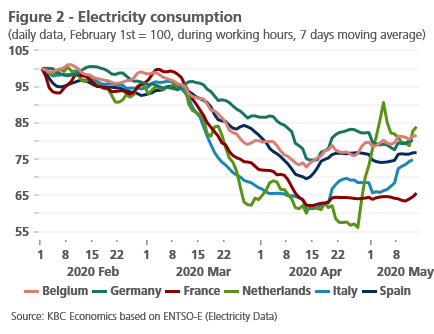

On the more positive side, high frequency data such as electricity consumption suggest that there may already be a bottoming out of economic activity and perhaps even some recovery in countries that have lifted lockdowns (figure 2). Indeed, the earlier lifting of lockdowns in Europe could mean that the trough of the recession will be slightly less deep than previously anticipated. At the same time, however, several factors suggest that the recovery thereafter could be less than robust. Recent surveys imply that businesses are cutting back on investment and plan to do so for a longer period of time. The sharp uptick in temporary unemployment could spill over and cause more structural problems for the labour market, meaning some of these jobs will not be immediately recovered. Furthermore, there is likely not a 1-to-1 relationship between lockdown measures and the economy. That is to say, even as lockdown measures are lifted, it is not clear if consumers will revitalize their spending, especially given the rise in temporary unemployment and ongoing health concerns. Finally, the outlook is quickly deteriorating on the external front too, as shipping problems continue to mount, and trade war risks appear to be resurfacing. In particular, the new confrontations between the US and China are a major concern as they may slow down the global economic recovery.

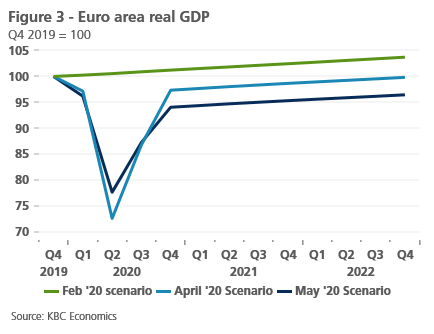

All this suggests that while we still expect the economic recovery to start in Q3 in the base scenario, this recovery will be somewhat more gradual or U-shaped. This means that GDP will take longer to return to its pre-crisis level. Indeed, by the end of 2021, we anticipate that euro area GDP will still be around 5% lower than where it was at end-2019 (figure 3). Thus, while our 2020 base case annual growth forecast remains relatively constant at -11%, we have revised down our 2021 growth figure to 6.9%.

Brexit is still here

While the COVID19 pandemic has inevitably shifted focus away from Brexit, it appears that very little progress has been made in talks between EU and UK officials that are supposed to guide a decision by end-June as to whether the UK will seek a further extension from the current effective exit date of December 31st 2020. Media speculation suggests the UK may stick to a previously strongly held position and not ask for an extension at that point. Instead, it is argued the UK may seek to win extra concessions in a rushed departure deal in the second half of the year. The priority being given at official level both in the UK and EU to the coronavirus means clear indications as to the timing of the UK’s exit from the EU and the nature of its subsequent relationship with the bloc could remain unclear for some time.

Unprecedented shock in the US

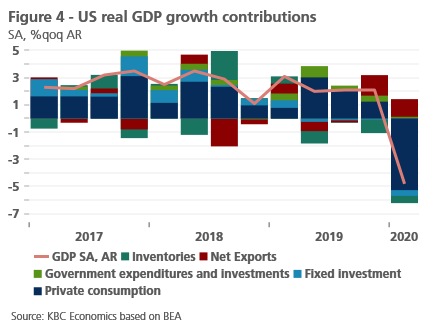

Like in the euro area, US Q1 GDP figures were much weaker than anticipated, despite lockdowns only coming into play at the very end of March throughout most of the country. Real GDP fell by 4.8% quarter-on-quarter annualized, pulled down in particular by a severe drop in private consumption (figure 4). And while the end of March saw sharp increases in the number of people claiming unemployment benefits, April was even worse for the US labour market, with 20.5 million nonfarm payrolls lost and a jump in the unemployment rate from 4.4% to 14.7%. Business surveys also continue to point to ongoing weakness in Q2 with the ISM manufacturing survey falling further to 41.5 in April and the ISM non-manufacturing survey falling to 26.0.

Despite the fact the virus spread has not yet peaked in many places in the US, several states have started to lift lockdown measures already. Perhaps even more so than in Europe, where there is at least some indication that case rates are declining, the US risks seeing further waves of the virus that will then force states to re-impose lockdown measures in the near future. Furthermore, we are continuing to see signs that the recovery in the US will not be a quick, V-shaped rebound. The high unemployment rate, in particular, threatens to cause longer lasting damage to the recovery as private consumption will likely continue to be weighed down. Furthermore, the fact that the curve has not yet flattened, means many consumers may still be wary about going out and resuming their consumption as usual. We therefore don’t expect to see a simultaneous economic recovery with the lifting of the lockdown measures. As such, we maintain our base scenario growth outlook of -8.0% in 2020 followed by a recovery of only 6.5% in 2021.

Mixed signals amid China’s recovery

China appears to have passed the worst of the crisis, with new Covid-19 cases remaining relatively limited and most of the Chinese economy once again open. After falling 9.8% quarter-over-quarter in Q1, GDP growth is expected to recover in Q2. However, more frequent data are providing mixed signals on the robustness of the recovery. On the positive side, certain monthly indicators, like fixed asset investment and industrial production, showed a clear monthly recovery in March, while vehicle sales in April even indicated positive year-over-year growth (+4.5%). By these metrics, the economic shock caused by Covid-19 indeed appears to have been temporary. However, business surveys for April paint a somewhat more concerning picture. The Markit services PMI, for example, remained in contraction territory in both March (43) and April (44.4). On the manufacturing side, new export orders in particular remain weak, with a deterioration from 46.4 in March to 33.5 in April. This may signal that the global negative impact of the coronavirus crisis will weigh on the Chinese recovery. Given the weakness in Q1 GDP, global spillover effects, and recent suggestions that US-China trade tensions may continue to flare up this year, we have downgraded our Chinese growth outlook to 1% in 2020. The expected recovery in 2021, however, is expected to be quite strong still at 8.8%.

A taxing moment for Japan

Japan is another advanced economy that is feeling the full brunt of the corona crisis. What’s more, it comes at an especially difficult time for the Japanese economy. It is still struggling with the impact of the rise of a consumption sales tax from 8% to 10% on 1 October 2019. As a result, quarter-on-quarter growth nearly stagnated in Q3 2019 (+0.1% annualised) and contracted sharply (-7.1% annualised) in Q4 2019. This means that the Japanese economy was already close to a so-called technical recession before the Covid-19 crisis began.

To mitigate the economic impact, on April 7 the government adopted the Emergency Economic Package Against COVID-19, with a total volume of 21.1 % of GDP. This package also takes into account the remaining part of the previously announced packages (the December 2019 stimulus package and the two COVID-19-response packages announced on February 13 and March 10 respectively). The largest part of the funds involved will be spent on the objective of protecting employment and businesses (16% of GDP) and ‘restarting and rebuilding’ resilient economic activity after the end of the virus containment phase (4.3% of GDP).

The Bank of Japan took supportive policy action as well. After taking measures to smooth the main functioning of financial markets (notably of U.S. dollar funding markets), the Bank of Japan decided at its April 27 monetary policy meeting to purchase any necessary amount of JGBs (in the framework of its Yield Curve Control policy) without setting an upper limit on its guidance on JGB purchases. In doing so, the Bank of Japan is in effect facilitating the government’s expenditure programme by de facto offering monetary financing for it.

Central Bank action dampening volatility

Volatility in equity markets, money markets (at least in the US), corporate debt markets and currency markets has clearly eased since late-March (see Box 3: FX markets returning to calmer waters). Much of this easing can be attributed to the significant measures introduced by central banks to improve liquidity and to expand their lending facilities, including through accepting a wider variety of collateral. Smaller central banks have stepped up their monetary stimulus too. The Czech National Bank, for example, lowered the deposit rate further in May 2020, from 1% to 0.25%. The Norwegian Central Bank also cut its main policy rate again to a record low of zero.

Still, there are several reasons for concern. First, intra-EMU spreads remain under pressure, with spread-widening particularly clear in Italy and the other non-core countries. Markets remain fundamentally concerned about Italy and other countries’ ability to finance their additional public debt in the future. Initial ECB communication may have unintentionally contributed to these concerns, although actual ECB market interventions indicate strong support biased towards Italy and other heavily indebted euro area member states. Second, the recent German court ruling on the ECB’s asset purchases caused a negative reaction in nervous markets too. The lasting impact of this decision is difficult to predict at this point. As the German court argued it had concerns about ‘proportionality’ as well as clear motivation in ECB asset purchase decisions, this could in theory raise issues around ECB independence from national governments and hence weigh on its credibility. However, the ECB and other EU institutions have quickly made it clear that the ECB is only subject to rulings by the European Court of Justice. Finally, the significance of the German court ruling is notably amplified by limited solidarity in the European fiscal response to the coronavirus crisis. The recent decision to provide support to EU member states from the European Stability Mechanism is clearly disappointing in scope and scale and insufficient for the Southern European economies hit hard by the crisis.

Given that these concerns are unlikely to disappear in the short term, we expect intra-EMU spreads may even widen further before easing moderately. These concerns are also expected to weigh on the euro vis-à-vis the dollar, and we therefore have lowered our expectation for the euro exchange rate through 2020.

Box 3 - FX markets returning to calmer waters

Early this year, volatility in the major currency cross rates, including EUR/USD, dropped to historically low levels. The relative monetary policy stance of the major central banks, an important driver for FX markets, was expected to stay unchanged for quite some time. The corona crisis succeeded in unlocking the stalemate. In early March, the dollar initially nosedived as markets understood that uncertainty on the Covid-19 pandemic would force the Fed to remove the dollar’s interest rate advantage. However, the FX market soon shifted into ‘red-alert’ crisis modus. And in times of extreme market stress, liquidity and volatility are the key interconnected drivers of global FX trading.

The US dollar remains the reference for international financing, irrespective of the economic performance of the US economy. In the context of extreme low visibility on the economy and market developments, most economic agents start hoarding USD to be able to meet upcoming financial commitments. At the same time, US banks may be reluctant to provide USD liquidity to foreign counterparties. Last but not least, in times of extreme market stress, prices in markets of less liquid assets (including currencies) are often highly disrupted. Only deep, liquid markets allow for executing transactions at sharp market prices. The dollar satisfies those criteria best, triggering a run to the US currency in mid-March.

Plenty of assets and currencies fell victim to fire sales with little consideration for valuations or prices. The currencies of emerging markets were especially hard hit. Liquidity in those markets is tighter than in developed markets. Some emerging markets’ dependency on USD funding is an additional disadvantage. Currencies from small countries with solid economic fundamentals (e.g. the Scandi currencies) didn’t escape from global market dynamics either and were sold without discrimination. Even gold often didn’t meet the test of sufficient market liquidity. The losses of the big, more liquid currencies like the euro and the yen were much more limited, but premiums in the option markets jumped higher.

The issue of availability of USD liquidity outside the US is, at least partially, solved. The Fed materially extended its FX swaps lines to foreign central banks. Via a new repo-facility it also provided USD liquidity (against collateral) to a broader range of international counterparties. Those measures and a congruent easing of global stress finally slowed the USD liquidity squeeze. For now, the dollar remains strong and the premia in the FX option markets stay well above early-2020 levels. Even so, several currencies have seen a solid comeback, such as the Swedish and Norwegian krone. The Aussie dollar also reversed a big part of its ‘corona sell-off’.

Monetary policy and, a fortiori, interest rate differentials currently have no major role to play as a driver of currency trading. Policy rates in most developed economies have been reduced to the ‘effec-tive lower bound’. That won’t change anytime soon. Over time, the economic damage and the pace of the economic recovery post-corona crisis might become important for the performance of currencies. In this respect, it’s no coincidence that currencies from countries with large (fiscal and/or monetary) firepower to support their economies or their currency (FX interventions) outperformed. In case of a flaring-up of uncertainty, demand for USD liquidity will still be in play, but we don’t expect a return to levels of stress recorded mid-March. Still, the corona crisis will remain a source of uncertainty in inter-national funding markets. As such, currencies of emerging markets, in particular those with a weaker credit profile (e.g. external deficits) will remain vulnerable.

Alle historische koersen/prijzen, statistieken en grafieken zijn up-to-date, tot en met 9 april 2020, tenzij anders vermeld. De verstrekte standpunten en prognoses zijn die van 9 april 2020.