Non-existent bankruptcy wave on the way after all?

During the pandemic crisis, surprisingly few companies went bankrupt in Belgium, mainly thanks to an extensive package of support measures. Now that these are being phased out, the bankruptcy rate is on the rise again, although it remains well below pre-Covid levels. The new shocks from the war in Ukraine (rising energy, material and labour costs, worsening supply problems, reduced product demand) are likely to increase that number further. However, it remains uncertain whether a major bankruptcy wave will emerge.

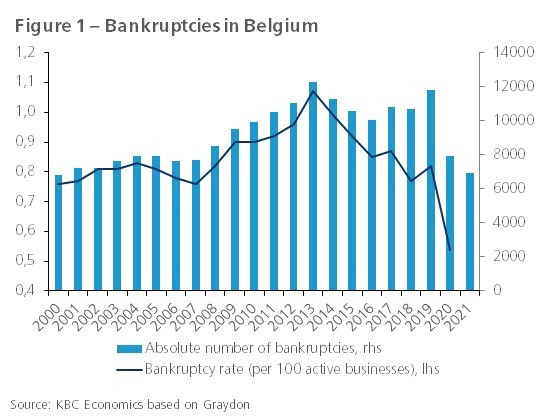

According to the business information office Graydon, 6,918 companies in Belgium went bankrupt in 2021. This figure is the lowest since 2000 and follows another low 2020 figure (figure 1). The favourable development is striking in the context of the severe economic shock caused by the pandemic. It is explained by the many protection mechanisms launched by the authorities to support the viability of businesses during the crisis. These included corona premiums and loans, the extension of the system of temporary unemployment, the granting of tax deferrals and the provision of moratoria on bankruptcies. The generally healthy financial situation of Belgian companies probably also played a role. Their resilience during the pandemic is also evidenced by the sustained increase in the number of start-ups. Many saw the crisis as an opportunity (e.g., web shop starters) or had been playing with the idea of starting their own business for some time and suddenly had time to work out their plans. All this ensured that the net growth of the number of businesses remained positive during the pandemic.

Link with economic climate

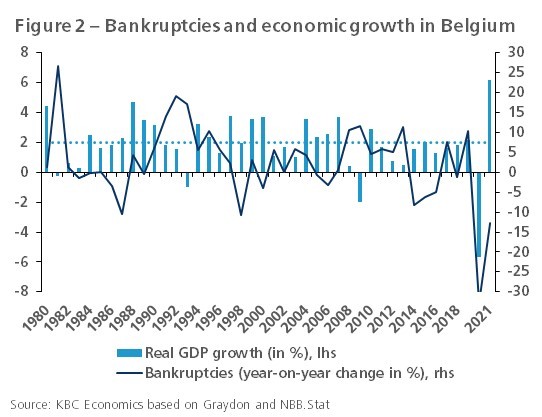

The disappearance of the link between economic growth and the dynamics of the number of bankruptcies in 2020-2021 is atypical (figure 2). While business failure is essentially a microeconomic phenomenon caused by firm-specific conditions, the overall economic situation often also plays a crucial role, especially in the form of reduced product demand. Macroeconomic factors tend to exacerbate the problems of companies already in difficulty for other reasons (e.g., poor management) and accelerate their demise. From 1980 to 2019, one percentage point lower GDP growth resulted on average in a 2.2 percentage points higher increase in bankruptcies.

During the economic downturn of the early 1980s and 1990s and the financial crisis of 2009-2012, the number of bankruptcies rose sharply. The increase was less pronounced during the period of weak growth in the early 2000s. The periods of relatively strong GDP growth (1984-1990, 1994-2000, 2004-2007 and 2014-2019) were accompanied by a decrease or limited increase in bankruptcies. In the past, economic growth of more than 2% was generally needed to reduce bankruptcies. This was not the case during the economic upturn from 2014 onwards. Although annual real GDP growth remained below 2% in 2014-2016, the drop in bankruptcies was solid.

The pandemic shows that caution is needed in interpreting bankruptcy data, as they are often influenced by technical and policy factors in addition to the business cycle. This was also the case in the years preceding the Covid crisis. In 2017, the law on ghost companies came into force, in 2018 the new insolvency law and in 2019 the new law for companies and associations. This new legislation resulted in more companies (including non-profit organisations and liberal professions) being able to be declared bankrupt more quickly. In addition, there were efforts by courts to clamp down on forms of fraud. All this resulted in an increase in the number of bankruptcies in that period (figure 2). Yet, we must put this into perspective. In absolute terms, the number of bankruptcies in 2014-2019 remained above the level before the financial crisis. This is, of course, partly due to the fact that during the economic upswing, more new businesses were set up, which in turn also led to more bankruptcies. The number of bankruptcies must therefore be seen relative to the number of active companies. Just before the pandemic, this failure rate decreased to a level comparable to the one existing before the financial crisis (figure 1).

Bankruptcies on the rise again

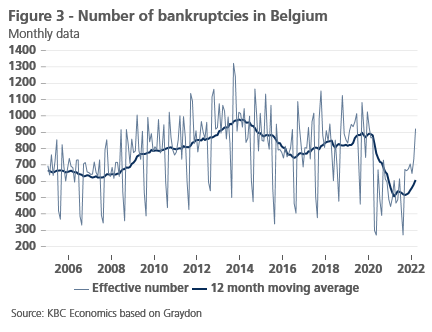

The latest figures show that the number of bankruptcies is on the rise again. In March 2022, bankruptcies were more than 50% higher than a year ago (figure 3). The increase is fairly general, but particularly strong in the catering and transport sectors. One explanation is the phasing out of the support that was in place during the pandemic, which is causing problems for companies without financial reserves. Another is that the tax authorities are resuming the writs of failure and commercial courts have also started to deal with cases from the crisis. The deterioration is not in itself a surprise. However, it does raise the question of whether this tipping point means a return to ‘normal’ bankruptcy figures or the start of a trend of significantly higher numbers of corporate failures. The economic consequences of the war in Ukraine suggest that the latter may be the case. They have created new concerns and risks for businesses, including rising energy, material and labour costs, worsening supply problems and reduced product demand. These headwind factors may contribute to the eventual failure of many companies, especially those also still struggling with the financial impact of the Covid crisis.

More generally, the classic link between the number of bankruptcies and the business cycle, which is deteriorating, will come into play again. With an expected GDP growth rate of still around 2% in 2022, a severe bankruptcy wave is likely to be avoided. What also speaks for this is that, according to the NBB, there is no clear indication of large-scale ‘zombification’ (i.e., no sharp increase in the number of unviable companies). Many business leaders recapitalised their companies during the pandemic crisis and revitalised their business models. Furthermore, a recent ad hoc survey by the NBB and some business and self-employed federations (conducted when the war in Ukraine had been going on for over a month) shows that 97% do not expect bankruptcy in the short term. This is a figure that is comparable or even better than during the past waves of the pandemic. Whether the tilt in the bankruptcy figures will eventually result in a bankruptcy wave remains uncertain. The coming months will be crucial.