Labour hoarding in uncertain times

Recently, we’ve seen a gradual negative turnaround in the Belgian labour market. The deterioration, linked to the war in Ukraine and the energy crisis, will not necessarily result in a sharp rise in unemployment in our view. Companies will hoard labour more than in similar previous cyclical phases. Indeed, there are factors that favour hoarding behaviour, which in itself is linked to the labour market tightness that companies faced during the recovery from the pandemic. First, the impact of the pandemic on companies’ financial health has, on average, been limited. This gives them some resilience in the current crisis and puts them in a better position to keep staff with them. Furthermore, the upcoming demographic contraction in the labour supply implies that once economic growth picks up after the energy crisis, the tightness may continue with even more ferocity.

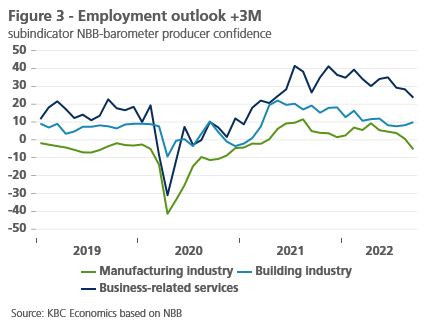

There have been signs in recent months that the situation in the Belgian labour market is turning negative. This is a consequence of the deterioration in the economic climate, which in turn is linked to the war in Ukraine and the energy crisis. For instance, Belgians’ fear of becoming unemployed in the next 12 months (a subcomponent of consumer confidence) climbed higher since the spring. Hard labour market data have also started to turn for some time (see Figure 1). The annual change in the number of jobseekers became less negative since early 2022 and has reached positive territory again in September. The harmonised unemployment rate climbed from a low of 5.3% early 2022 to 5.8% during the summer.

KBC Economics expects Belgium’s quarterly real GDP growth to turn negative in the second half of the year and economic activity to remain stagnant in early 2023 as well. Still, we do not think unemployment will rise sharply in this context. There are several reasons for this. A first is that the expected economic contraction is likely to remain limited. Only should energy shortages become critical and/or energy prices remain permanently high could the situation turn into a much deeper recession. Although this negative risk is not negligible, we do not assume it in our base scenario. A second reason is that firms are likely to hoard labour more than ever.

Labour hoarding and nurturing

It is common for well-performing companies to refrain from rapid layoffs during an economic downturn. This is certainly the case when there is still a lot of uncertainty about the extent and duration of the slowdown or when companies assume that a production recovery will return soon. By hoarding labour, they hope to avoid jeopardising future production potential. The phenomenon of labour hoarding is particularly prevalent today, and specifically in Belgium, for a number of reasons. First, just before the outbreak of the energy crisis, the Belgian labour market had again become exceptionally tight, especially in a European perspective. The robust recovery from the pandemic meant that a lot of companies had too much work for their current staff. Many vacancies could not be filled. A little drop in demand is then no reason to show workers the door. Moreover, the shortage implies that those who employ good staff will not let them go just like that. Finding and engaging suitable staff (especially for bottleneck occupations) is a time-consuming activity, which does not always yield (the desired) results.

Furthermore, employee layoffs, as well as possible rehiring when demand picks up again, involve a lot of costs for companies. Comparative research by the law firm Laga shows that Belgium is even among the group of European countries with the highest dismissal costs. Another factor is the average high level of education of Belgian workers. Often, labour hoarding is relatively more applicable to higher educated people, especially when additional expertise and experience has been built up in the company itself.

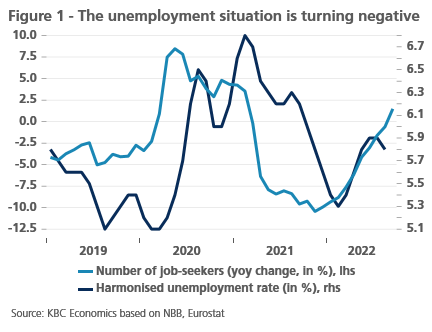

Finally, there are factors that add to labour hoarding today (see Figure 2). Although the covid-19 pandemic had a major impact on the turnover of many companies, its impact on their financial health has generally been limited. In other words, profitability and solvency, on average, did not suffer badly from the pandemic. This makes companies more resilient to the energy crisis and puts them in a better position to keep their staff with them. Also peculiar to the current situation is that negative demographics are responsible for the rapidly returning labour market tightness and are increasingly making themselves felt in the labour market. In its latest demographic projections, the Federal Planning Bureau assumes that the working-age population (20-64 year-olds) will effectively start shrinking in the coming years. The upcoming contraction in labour supply means that, once economic growth picks up after the energy crisis, tightness threatens to continue with even greater intensity.

Unemployment rate moderately higher

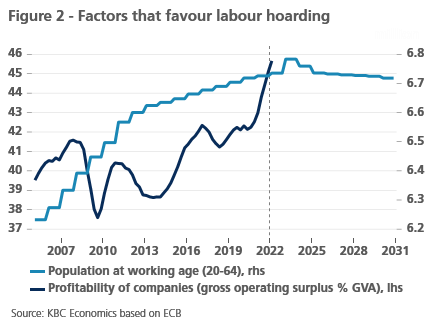

Labour market figures are likely to deteriorate further in the coming months. A genuine labour market crisis is unlikely to materialise, however. Specifically, we assume that the harmonised unemployment rate in Belgium will rise slightly to 6.2% by the end of 2023, coming from 5.8% this summer. It is hopeful in this regard that companies’ employment prospects are holding up quite well so far, even if they only cover the next three months (see Figure 3), in contrast to the more general sentiment indicators. That said, the risk of a more negative scenario, where unemployment does rise more sharply, remains high. Such a scenario would occur should the energy crisis deepen or last longer than expected, with some energy-intensive companies going belly up or thinking of leaving Belgium for good.