Economic Perspectives May 2025

Read the full publication below or click here to open the PDF.

- As financial markets were rattled by the excessive US tariffs announced on Liberation Day, Trump paused the so-called reciprocal tariffs for a period of 90 days (while maintaining the 10% universal tariff). Talks in Geneva also pushed tariffs back down for a period of 90 days, with the US now charging 30% on Chinese goods and China charging 10% on US goods. While avoiding a full decoupling of the Chinese and US economies, these tariffs remain at very elevated levels and will have a major impact on bilateral trade.

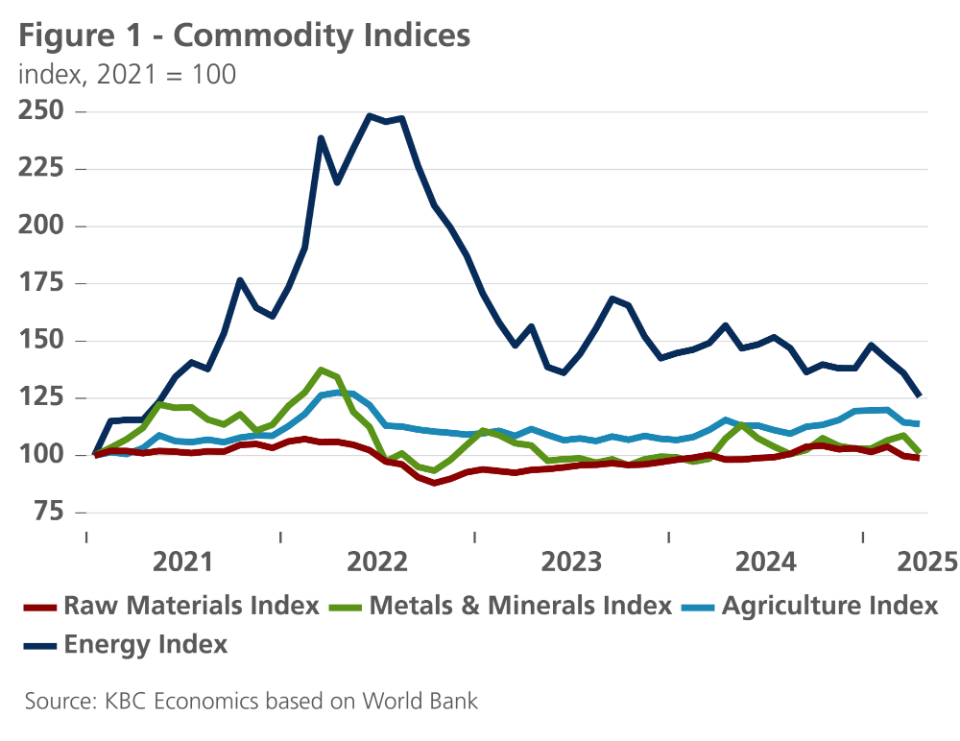

- Commodity prices declined in the wake of Liberation Day. Energy prices in particular showed steep declines. Oil prices declined by 18% last month to 61 USD per barrel. Though the decline was primarily driven by demand concerns, the decision of OPEC+ to ramp up production also drove down oil prices. Gas prices declined by 24% last month, partly demand-related, but also partly driven by favourable weather conditions and the EU’s easing of refilling requirements.

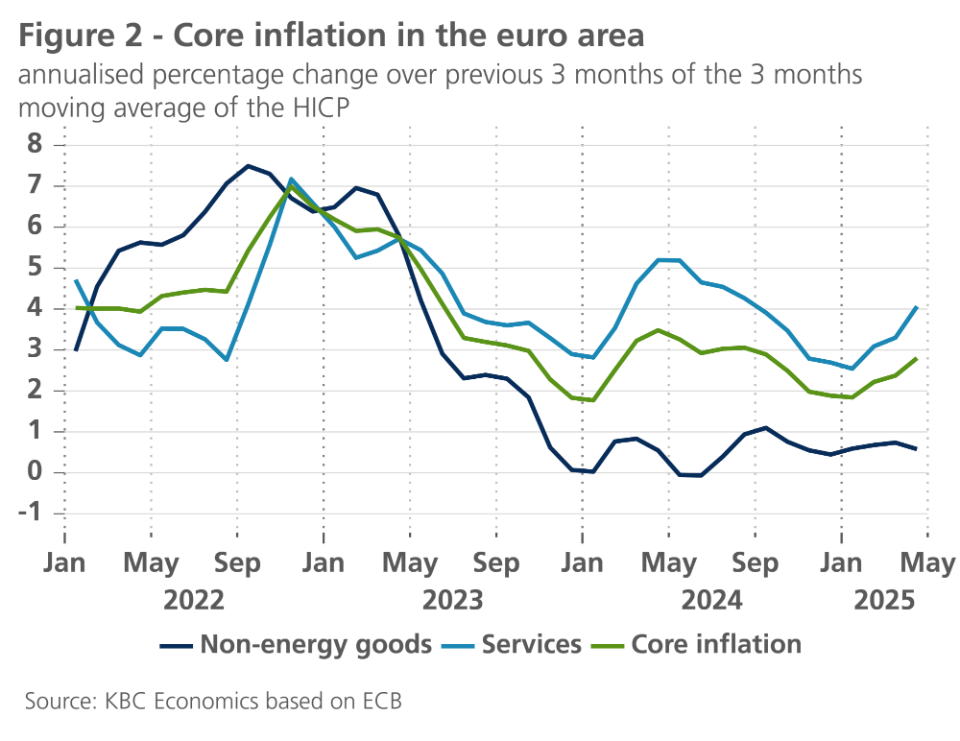

- Euro area inflationary pressures (temporarily) resurfaced in April. Though energy prices dropped significantly and the euro appreciated against the US dollar, euro area inflation remained steady at 2.2%. Meanwhile, core inflation increased from 2.4% to 2.7%. The increase was primarily driven by a spike in services inflation. That said, moderating wage pressures indicate lower services prices ahead. Furthermore, low energy prices, a strong euro and potential disinflationary effects from trade diversion are expected to drive inflation further down. We downgrade our inflation forecast from 2.6 to 2.1% for this year and from 2.6% to 1.9% next year.

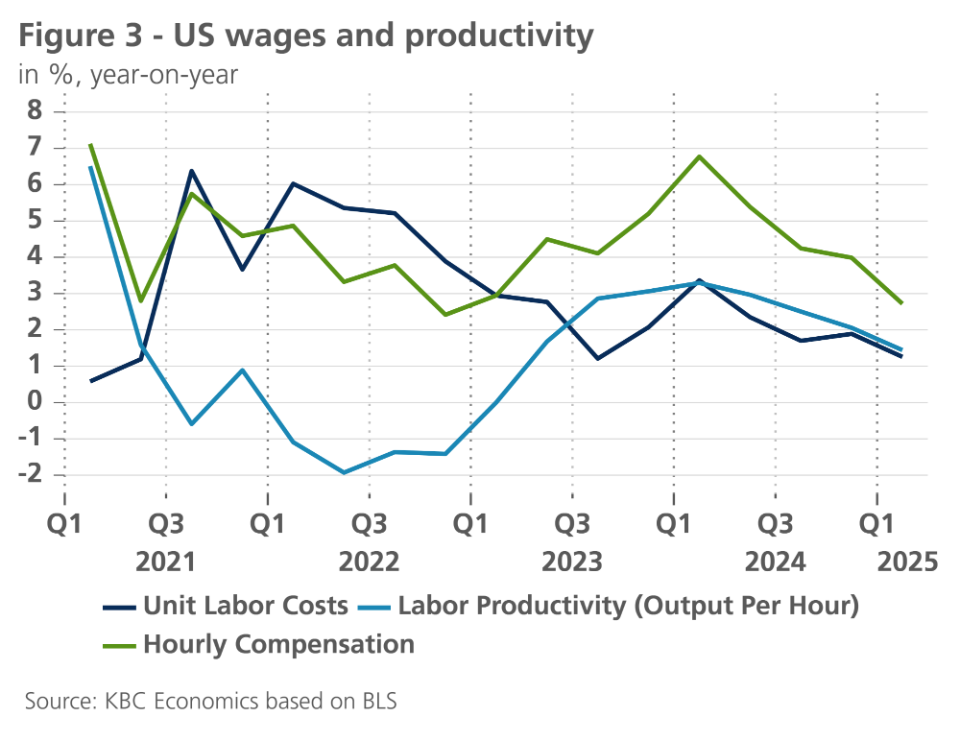

- US inflationary pressure again moderated in April as headline inflation declined from 2.4% to 2.3%, while core inflation remained at 2.8%. Food prices declined, while shelter and services prices increased modestly. Modest goods inflation suggest tariffs have yet to impact prices. Given lower energy prices and the decent April figure, we lower our forecast from 3.2% to 3.0% for 2025 and from 2.9% to 2.8% for 2026.

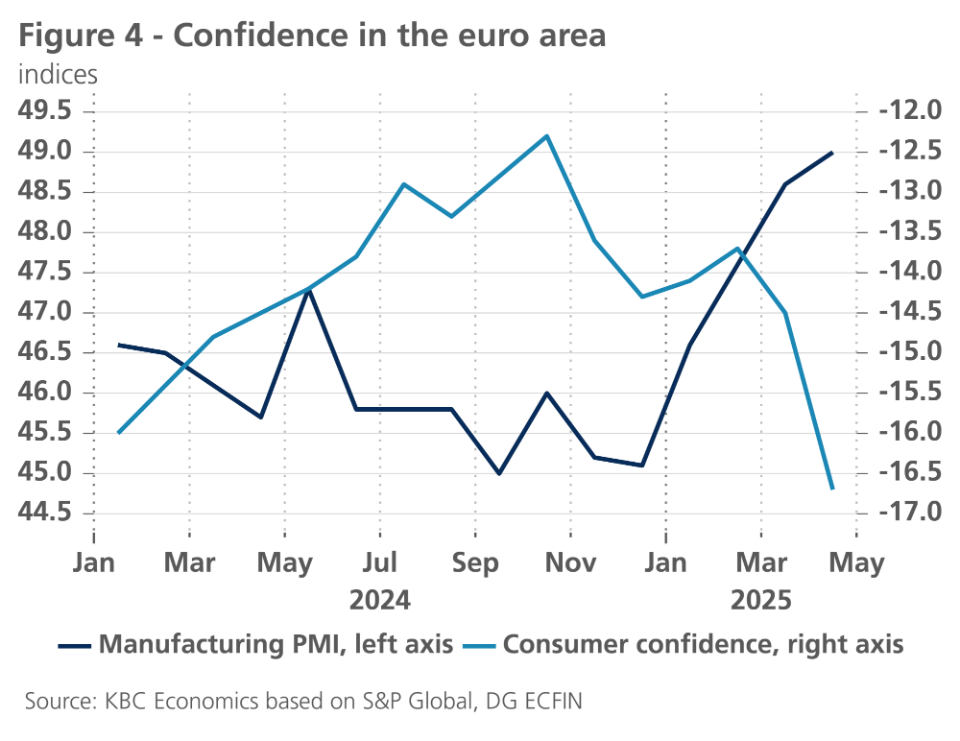

- Euro area GDP increased by 0.4% last quarter. Though the increase was partly influenced by a strong increase in Irish growth, ex. Ireland GDP increased by 0.2% quarter-on-quarter. That said, the US trade war is weighing on sentiment as consumer confidence deteriorated significantly and business sentiment weakened (especially for services). The labour market remains strong, however. We maintain our 0.9% 2025 growth forecast, but downgrade our 2026 forecast from 1.2% to 0.9%.

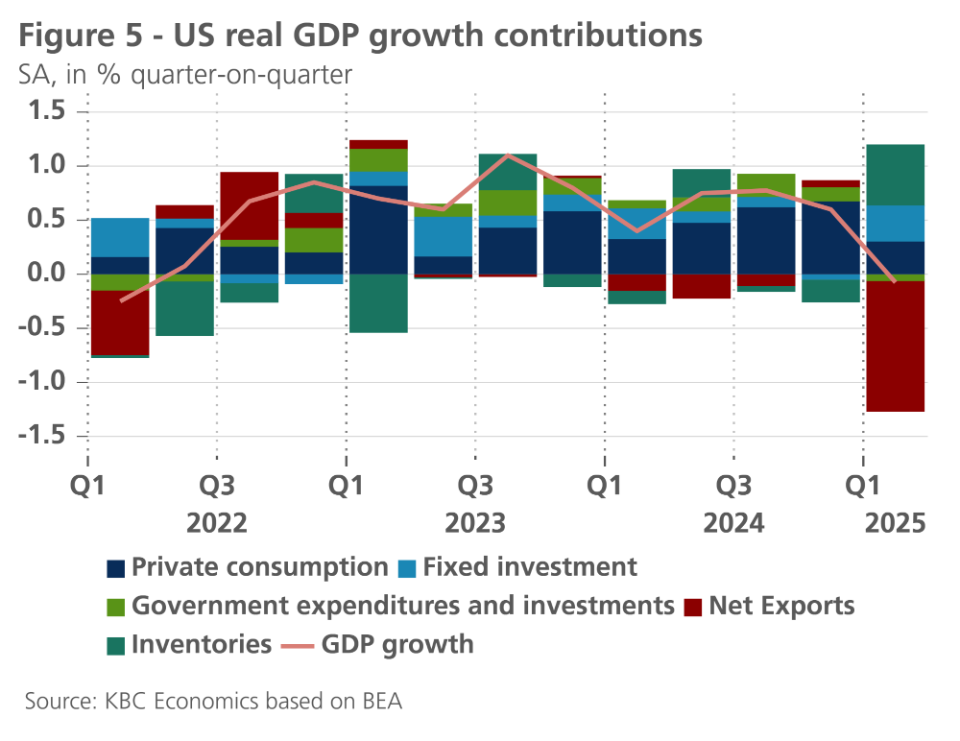

- Trump’s policies are already impacting the US economy as US real GDP shrank by 0.1% in the first quarter, a sharp reversal from last year’s high growth figures. Net exports made a strong negative contribution, which was partly compensated by high inventory and equipment spending growth. Consumer spending made a notably weak contribution. The labour market remains in healthy shape, however. Higher tariffs and elevated policy uncertainty will be a drag on growth in the coming quarters. We thus lower our GDP forecast from 1.8% to 1.1% for 2025 and from 1.8% to 1.2% for 2026.

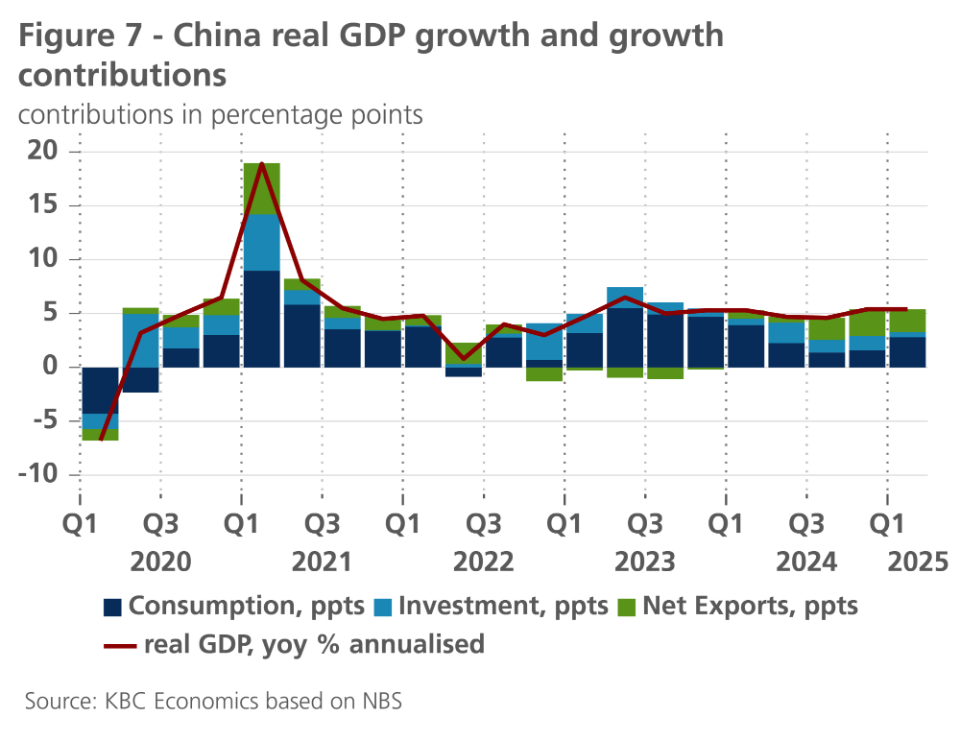

- China’s strong first-quarter GDP figures of 5.4% growth year-on-year will be hard to replicate in the coming quarters, as the US-China tariffs will hurt China’s export-dependent economy and the real estate crisis is still ongoing. Confidence indicators are edging downwards and lacklustre inflation dynamics point to soft underlying demand. The recently announced 10-point monetary policy package will support the economy, but is not overwhelming. We downgrade our 2025 forecast from 4.7% to 4.2%, while maintaining our 4.1% 2026 forecast.

- The Fed’s dual mandate comes under tension given lower growth and elevated inflation expectations. Therefore, the Fed remains in wait-and-see modus. We expect the Fed to proceed cautiously and cut rates three times in the second half of the year. The ECB doesn’t face the Fed’s policy dilemma as both the growth and inflation outlook point downwards. We expect two more rate cuts, putting the policy rate slightly below neutral.

- Trump’s trade policies and his attacks on the central bank have eroded the dollar’s safe-haven status. After Liberation Day, the dollar depreciated significantly against the euro (and other currencies). This happened despite an increase in US Treasury-Bund spreads, suggesting increased risk premia on US Treasuries. CDS and term premiums on US Treasuries also increased, showing decreased confidence in the US government. We expect further moderate dollar depreciation in the years ahead, given ongoing diversification of international central bank reserves and portfolio rebalancing.

Liberation Day created a rupture in global trade relations. Though Donald Trump paused the so-called reciprocal tariffs, he still raised the average effective tariffs on goods coming into the US to levels not seen since the Great Depression of last century (from 2.3% to 13%) as the 10% universal tariff remains in place. US-China tariffs reached exorbitant levels in April with the US imposing 145% tariffs on Chinese goods and China imposing 125% tariffs on US goods. If these tariffs would have remained in place, a trade stop between the world’s two largest economies would have occurred. Talks in Geneva lowered tensions as both sides agreed to lower tariffs for a period of 90 days. The US now levies 30% tariffs on Chinese goods, while China levies 10% tariffs on US goods. While avoiding a full decoupling of the US and Chinese economies, these tariffs will still have a major impact on bilateral trade, however.

China aside, an open question is how high reciprocal tariffs on other countries will eventually be. For now, we assume some reciprocal tariffs will be put in place after the 90-day pause ends (on top of the current 10% universal tariff), though we assume they will be lower than the tariffs announced on Liberation Day. We thus assume a 15% effective tariff on EU goods and a 25% effective tariff on non-China Asian goods. We assume other countries will only face the 10% universal tariff.

Trump’s erratic trade policy and his attacks on the Fed have caused major turbulence in the financial markets. The most important consequence has been a partial loss in the safe-haven status of the dollar. In the wake of Liberation Day, the dollar depreciated against the euro (and other currencies). This depreciation happened despite an increase in US Treasury-Bund spreads. CDS and term premiums on US Treasuries also increased, showing decreased confidence in the US government.

The trade war is already impacting US economic growth. Last quarter US GDP contracted as net exports made a big negative contribution and consumption growth slowed materially. Other major economies have yet to feel the impact of increased US protectionism. Indeed, both China and the euro area posted solid growth figures last quarter. This is unlikely to last as US tariffs have yet to impact their economy.

Commodity prices decline steeply in April

As Liberation-Day tariffs are expected to cause a major slowdown in global growth, commodity prices plunged in April (see figure 1). This is especially the case for energy prices. Oil prices declined by 18% last month. Though partially demand-driven, the decline was also caused by OPEC+ steadily ramping up supply more than expected. Earlier in the month eight OPEC+ members announced supply increases of 411k barrels per day in June, on top of a 411k barrel per day increase in May. Tensions have been rising within the cartel as Kazakhstan, the United Arab Emirates and Iraq repeatedly disrespected their quotas. Increasing non-OPEC+ market share also induced OPEC+ to raise its oil output.

Gas prices decreased by 24% last month to 32 EUR per MWh. Though the decline was again demand-driven, other factors were also at play. Favourable weather conditions reduced demand for heating and boosted renewable energy supply. As anticipated, the European Parliament also voted in favour of relaxing its refilling requirements earlier this month. Negotiations with member states will now start to finalise the legislation. In this proposal, the refilling requirement would be lowered from 90% to 83% of total capacity. This target could be met at any time between 1 October and 1 December. Countries could also deviate from this target by four percentage points in the event of unfavourable market conditions. At 42% of total capacity, gas reserves are now slightly below average levels.

Other commodities also declined last month. Metals declined by 7%, in anticipation of lower demand. Copper, a cyclical metal, saw prices decline by 5.8%, while iron ore prices declined by 4%. Other metals saw even bigger declines, e.g., tin declined by 15%. In contrast, gold prices increased by 5.2% given gold’s safe-haven status. In contrast to other commodities, food prices remained broadly unchanged as a decline in sugar and vegetable oil prices was compensated by increasing cereal, dairy and meat prices.

Stable euro area inflation

In the euro area, inflation stood at 2.2% in April, unchanged from the previous month. However, the stabilisation masks an increase in core inflation from 2.4% to 2.7%, whose impact was neutralised by a fall in energy price inflation from -1.0% to -3.5%.

Within core inflation, the rise in services inflation from 3.5% to 3.9% raised eyebrows in particular. The exceptionally strong month-on-month rise in April is probably related to calendar effects, and in particular the fact that Easter fell relatively late. Prices of tourism-related services usually increase in the run-up to Easter, and that increase in 2025 is presumably concentrated in April. But since in the previous four months the (expected) cooling in services inflation seemed to stall, the rebound in April still raises some doubts about the strength and pace of the disinflation process (see figure 2). We nevertheless assume it will resume, as wage growth figures continue to point to a gradual further cooling.

Furthermore, quarterly non-energy goods inflation has been hovering around the low level of just below 1.0% since the summer of 2024. The recent appreciation of the euro may lower that pace even more. Also, it looks like any retaliatory measures by the EU in the context of the trade war will remain even more limited and targeted than we initially expected. As a result, we no longer assume that they will fuel inflation.

We therefore lower our forecast for core inflation from 2.9% to 2.5% for 2025 and from 3.2% to 2.2% for 2026. Moreover, the recent fall in energy prices combined with the recent strengthening of the euro sets the stage for a further, and larger than previously expected, fall in energy price inflation in the coming months. This leads us to lower our forecast for headline inflation in the euro area from 2.6% in both 2025 and 2026 to 2.1% in 2025 and 1.9% in 2026.

US inflation moderates in April

US inflation continued its descent in April as headline inflation declined from 2.4% to 2.3%, while core inflation remained unchanged at 2.8%. Most components were rather soft. Food prices declined marginally thanks in part to a 12.7% drop in egg prices.

Shelter prices showed a mild increase of 0.3% month-on-month, thanks to a modest drop in hotel prices. Other rent components (i.e., owner-equivalent rent and rent of primary residence) were firmer, however. That said, the decline in new tenant rent prices point to lower inflation impulses in these components as well.

Core service prices (ex. shelter) also moderated, growing 0.2% month-on-month. There were some notable declines in recreation services and education and communication services. Airline fares continued their descent.

Encouragingly for future service price inflation, wage pressures have moderated. Indeed, average hourly earnings increased by only 0.16% last month. That said, as output declined last quarter, labour productivity declined as well in the first quarter. This pushed up unit labour costs on a quarterly basis, though the growth trend is still declining in year-on-year terms (see figure 3).

Core goods also remained under control, increasing by only 0.1%. It seems that tariffs have thus yet to filter through in consumer prices. Used cars and trucks prices ticked down. Forward-looking indicators have firmed lately for this important category.

The most noteworthy increase came from energy prices, which rose 0.7% last month, due to large increases in utility prices. Gasoline prices remained broadly unchanged, however, indicating that the post-Liberation Day decline in energy prices has yet to filter through.

All in all, given the soft April inflation data and the recent descent in energy prices, we bring down our forecast for US inflation from 3.2% to 3.0% for 2025 and from 2.9% to 2.8% for 2026.

Stronger than expected growth in euro area

The preliminary flash estimate of real GDP in the euro area points to growth of 0.4% in the first quarter of 2025 versus the last of 2024. This was significantly higher than our expectation (0.1%). A major part of the better-than-expected growth is explained by the particularly strong expansion of the Irish economy (+3.2% on a quarterly basis), which was probably boosted by exports to the US in anticipation of the increase in import tariffs. According to figures from the US Census Bureau, US imports from Ireland in March 2025 nearly tripled (in value and in euro) compared to the year before.

Excluding Ireland, growth in the eurozone economy was only half as much (0.2%). That is still higher than our initial expectations. Spain remained the frontrunner with 0.6% growth, while Italy also grew remarkably strong (0.3%). Encouragingly, the German economy posted 0.2% growth after contracting by 0.2% in the last quarter of 2024. France recorded growth of 0.1% - rather modest in this context.

The limited information available on the composition of growth suggests that domestic demand mainly underpinned growth, with an important contribution from inventories. The contribution of net exports was negative in France, Italy and the Netherlands. This suggests that there was no general (strong) growth impulse due to frontloaded exports to the US.

Against the backdrop of tumultuous developments on the tariff front and the significant weakening of consumer confidence, business confidence indicators were not too bad overall, at least according to the surveys with purchasing managers (PMIs), and particularly in manufacturing (see figure 4). In the services sector, a sharp deterioration was recorded, especially in the European Commission surveys. In construction, the loss of confidence remained more limited, with construction PMIs even pointing to a significant improvement in confidence, partly due to the improvement in Germany.

The latter is no doubt linked to the sharp easing of the constitutional debt brake on German public finances at the end of March. Among other things, this allows for a substantial expansion of investments, as well as an – in principle unlimited – increase in defence spending (both will take time to be implemented). With the new German government taking office, time will tell how this will be implemented in concrete terms. The 2025 budget will hopefully get approved before the summer holidays, although that is not a certainty. The prioritisation of defence spending is on the government's agenda for autumn. All this makes it clear that the stimulative effect of the new German government's fiscal policy in 2025 will still be very limited, especially as all other potentially stimulative fiscal measures in the coalition agreement have been explicitly made conditional on a ‘Finanzierungsvorbehalt’. That is, they can only be implemented if there is financial room for them.

That the stimulus from German fiscal policy would still be very limited in 2025 and would only come into full swing during 2026 and especially 2027 is in line with our initial assessment. Meanwhile, the US tariff war is more intense than initially anticipated and will thus have a larger impact on our forecast. We have therefore lowered our growth forecast for euro area real GDP in the last three quarters of 2025 and the first half of 2026 by a total of 0.5 percentage points (cumulated). In the expected annual average growth rate for 2025, this reduction is fully offset by the stronger-than-expected growth in the first quarter. We thus maintain the expected annual average growth rate of real GDP in the euro area at 0.9% for 2025. However, we reduce the expected annual average growth rate for 2026 from 1.2% to also 0.9%, given continued trade uncertainty.

Economic uncertainty already hit US economy

The US is already feeling the impact of Trump’s trade policies. US economic growth turned negative last quarter, the first negative figure since the first quarter of 2022. US real GDP decreased by 0.1% quarter-on-quarter (see figure 5). The decline was primarily driven by a large 1.2 percentage points negative quarter-on-quarter contribution from net exports. Imports surged by 10.3% quarter-on-quarter in anticipation of higher tariffs. The negative net exports contribution was partly counterbalanced by positive contributions elsewhere, however.

Inventories made a positive quarter-on-quarter contribution of 0.6 percentage points, as warehouses are getting filled with imported goods. In similar vein, equipment spending made a strong 0.3 percentage points quarter-on-quarter contribution, likely due to an increase in foreign-made equipment. Given the uncertain business climate, this elevated equipment spending is unlikely to be repeated in the coming quarters.

The most worrisome figure in the GDP report was the low contribution of consumer spending. Indeed, despite continued tariff induced anticipatory spending, consumer spending only made a 0.3% quarter-on quarter contribution (down from 0.65% last quarter). Durable goods spending declined by 0.85% quarter-on-quarter due to lower vehicle spending. Services spending also made a lower contribution, in large part because a 1.5% quarter-on-quarter drop in food services and accommodation spending. Though this drop could partially be weather-related, it could also be a sign that consumers are starting to cut back on non-essential spending. Indeed, consumer confidence has dropped steeply recently, suggesting lower consumption ahead. That said, auto sales were elevated in April, a positive sign for second-quarter GDP.

Producer confidence indicators also point to a slowdown, though they have not decreased dramatically. Services PMIs (S&P Global and ISM) have trended downwards and are now just above 50, suggesting a mild expansion. Manufacturing PMIs remain in contractionary territory overall, though they are well above September 2024 lows. These more elevated manufacturing PMI figures are boosted by high inventory growth, however. This component is temporarily boosted in anticipation of tariffs and is likely to weaken in the coming months.

Notwithstanding the ongoing DOGE cuts in federal government jobs, the labour market remains in decent shape. The labour market added 177k jobs last month, while the unemployment rate remained steady at 4.2%. The participation rate even slightly increased (from 62.5% to 62.6%). There was also a notable decline in the number of people employed part-time for economic reasons (-90k). The only concerning elements in the labour market reports was the decline in job openings, but even this decline is not dramatic.

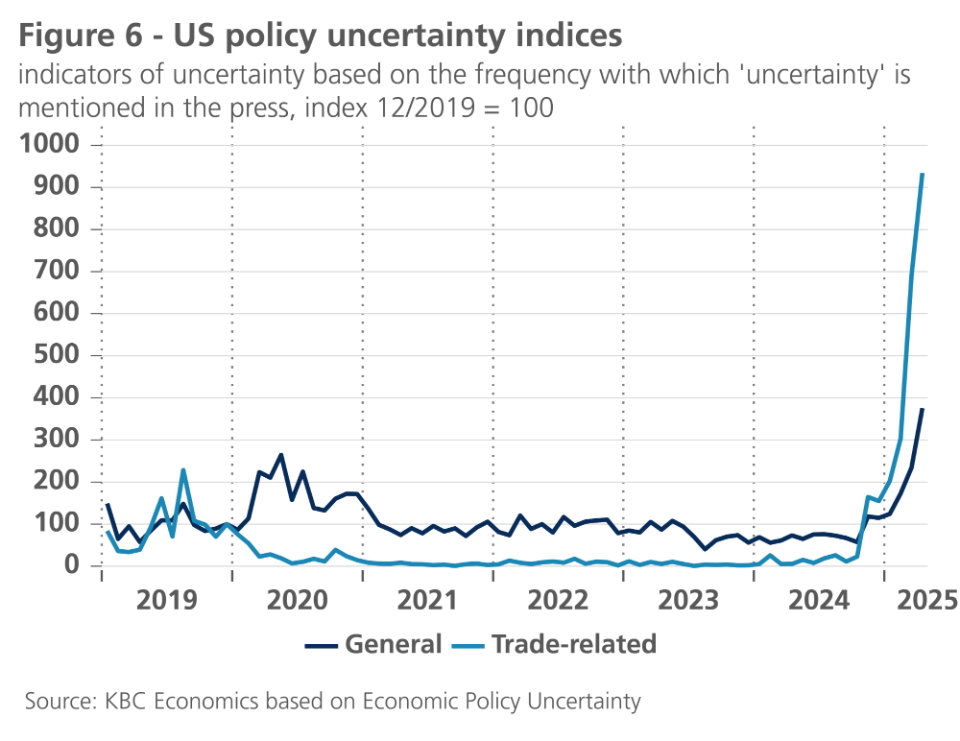

The quarters ahead are likely to remain challenging given the post-Liberation Day increase in tariffs. Furthermore, US policy uncertainty (especially towards trade) is at historic levels, which will weigh on future investments (see figure 6). Given these unwelcome developments and the lower first-quarter growth figure, we downgrade our growth forecast from 1.8% to 1.1% for 2025 and from 1.8% to 1.2% for 2026.

Tariff war to dampen Chinese growth

The past month has again been tumultuous for China. The country received the highest so-called reciprocal import tariff out of all countries from president Trump on Liberation Day. This triggered a tit-for-tat race to the top in April that lifted additional tariffs to staggeringly high levels. At the peak, China imposed a 125% tariff on US goods, while the US landed at a 145% tariff on Chinese goods. Both governments carved out sweeping exemptions for specific goods like pharmaceuticals, aircraft engines, semiconductors and consumer electronics but for those goods that were not exempt, tariffs at these levels fundamentally cease functioning as traditional tariffs in many cases and effectively become embargos leading to an effective decoupling of the economies.

Another important trade order of president Trump that came into effect in May is the removal of the so-called “de minimis’ exemption. This ends the long-standing duty-free access for low-value (<800 USD) shipments from China and Hong Kong to the US. Trump had briefly halted this loophole in February, but had to pause the cancellation after millions of packages started to pile up at customs as it proved challenging for customs officials, delivery companies and retailers to process these packages under the new rules.

After a meeting between Chinese Vice Premier He Lifeng and US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and US trade representative Jamieson Greer in Geneva, an agreement was struck to lower tariffs for a period of 90 days. The US brought its tariffs on Chinese goods down to 30% (including the 20% tariffs Trump announced before Liberation Day) while China reduced its tariffs on US imports to 10%. We think it is unlikely that tariffs will go back to the previous peaks after the 90-day break but future increases cannot be ruled out entirely. Talks to reach a trade deal between the two countries could still derail and the risk of new product groups being targeted by the Trump administration also persists.

The impact of the exceptionally high tariffs in April and the beginning of May was visible in the number of ships and cargo planes leaving China and entering the US. The PMI business sentiment indicators for April are also pointed to weaker growth ahead. The headline manufacturing and non-manufacturing PMI figures, from both the S&P Caixin and the official NBS surveys, all fell in April and are hovering around the neutral level. The subindicators for production and new export orders saw the strongest declines. The PMIs will likely improve going forward as the tariff peak is behind us, but we do expect that elevated uncertainty and volatility will continue to weigh on confidence in the medium term.

The expected weakness in the second quarter stands in contrast to the better-than-expected first-quarter real GDP growth figure, which showed GDP expanding by 5.4% year-on-year annualised (see figure 7). The surge in foreign trade was one of the major contributors to growth. This was widely expected because of the frontloading of exports to the US in anticipation of higher tariffs. Growth in the first quarter was also underpinned by ongoing policy support, such as the extension of the consumer subsidy scheme and the corporate equipment renewal program. These plans helped to lift investments and consumption by encouraging consumers and businesses to upgrade large articles such as cars, machinery, white goods, and furniture.

China’s national bank, the PBOC, added another support measure to the policy mix in May by announcing a 10-point monetary policy easing package. This package included a 0.10 percentage points cut to the key policy rate (the 7-day reverse repurchase rate), which brings the policy rate to 1.4%. The central bank also lowered the reserve requirement ratio, which determines the amount of cash banks must hold in reserves, by 50 basis points.

The monetary policy support package could provide some support to the economy but it is unlikely to move the needle much as the Chinese economy is currently relatively insensitive to interest rate changes. The Chinese government has announced that it is currently working on a new plan to support small and medium enterprises and the private sector, but we have to wait for further details.

Based on the sizeable escalation of the US-China trade war and the (lower but) still elevated US tariffs on Chinese goods imports, the expected global economic slowdown and the relatively limited size of government support measures at the moment, we downgraded our real GDP growth forecast for 2025 from 4.7% to 4.2%. For next year, we upgraded the quarterly growth path as the economy is likely to recover after the 2025 slowdown on the back of some relaxation in trade tensions and more government support. This results in an unchanged annual growth rate of 4.1%, however, given the lower 2025 base.

On the inflation front, we expect to see some upward pressure coming from Chinese tariffs on US imports (especially on agriculture products like pork) and from domestic support measures. However, these price pressures will likely be more than compensated by the slowdown in domestic and global growth and the expectation that the overcapacity from lower US demand will flood the domestic market. This, together with the lower-than-expected March inflation figure, made us decide to lower our 2025 CPI forecast from 0.6% to 0.0%. For 2026, we downgrade our inflation outlook from 1.9% to 1.2%.

Diverging monetary policy between Fed and ECB

The Fed and the ECB are currently in substantially different policy situations. The Fed faces a policy dilemma. Indeed, the two objectives of its dual mandate, namely both price stability and maximum employment, require interest rate decisions in opposite directions.

On the one hand, the Fed assesses that the US labour market still shows signs of resilience. This is reflected in overall still solid job growth. In April, employment increased by 177k jobs on balance. Moreover, the unemployment rate remained stable at 4.2% in April, a low figure in historical perspective. According to Fed Chairman Powell, those data fulfil the criterion of maximum employment. Moreover, since growth in average hourly earnings is moderating (but remains positive in real terms), the Fed sees no significant inflation risk stemming from the US labour market.

On the other hand, Powell also refers to the sharp economic policy uncertainty, in particular trade policy with import tariffs. The tariffs announced by the US president on 2 April were much higher than expected, according to the Fed, and furthermore, their impact on the economy is particularly difficult to predict. If the tariffs are maintained (and thus the 90-day suspension would not lead to permanent postponement), the Fed expects a stagflationary effect with lower growth and higher inflation. It indicated this back in March in its economic forecasts, known as dot plots. Specifically, then, the risks are a rising unemployment rate and higher inflation in the short term.

This leads to the Fed's policy dilemma: the risk of a rising unemployment rate should actually prompt the Fed to cut its policy rate now, but shorter-term inflation expectations that are incompatible with price stability do not allow for such easing. The Fed does take into account that import tariffs could possibly trigger only a one-off increase in the price level, in other words a temporary inflation that 'passes itself'. But that assumes that longer-term inflation expectations, currently in line with the Fed's 2% target, remain anchored at that level. To avoid second-round effects that would turn temporary inflation into sustained inflation, the Fed does need to remain cautious in its policy stance.

On balance, at its policy meeting on 7 May, the Fed kept its policy rate unchanged at 4.375%. Moreover, it also indicated that the timing of any policy change would depend on the further development of the outlook and risks. We expect that the Fed will take a wait-and-see approach for the rest of the second quarter, and then cut its policy rate by a total of 75 basis points during the second half of the year. After a final rate cut in the first quarter of 2026, the bottom will then most likely be reached in this interest rate cycle.

The policy decision for the ECB is less ambiguous than for the Fed. Both downside growth risks and especially the financial markets' remarkably low inflation expectations for the year ahead pointed unequivocally in the direction of rate cuts. The sharp fall in short-term inflation expectations is caused by the negative demand shock of US trade tariffs, with limited 'retaliation' from the EU, the risk of a shift in export paths of Chinese goods from the US to the EU, and finally also by the sharp appreciation of the euro making imports cheaper.

Consequently, the ECB cut its deposit rate by 25 basis points to 2.25% at its April policy meeting. ECB President Lagarde called this new level no longer restrictive, which means that the ECB assumes that its policy rate is now in a neutral zone. Apart from that, further decisions remain data-dependent as usual and the ECB does not commit to a specific interest rate path.

The end of the ECB's easing cycle is thus approaching, but has not yet been reached in our view. The ECB is likely to cut its policy rate two more times by 25 basis points each time. This will probably happen at the June and September policy meetings, since at that time new forecasts from ECB economists will also be available. The cyclical floor rate of 1.75% is likely to be slightly lower than neutral, meaning that at that point the ECB will provide mild stimulus to the European economy as a precautionary measure. When the European economy no longer needs that stimulus, the ECB may adjust its policy rate back to neutral, which at the moment may well correspond to a deposit rate of around 2%.

Bond yields between growth fears and risk premia

Since the shock of the announcement of so-called 'reciprocal' trade tariffs on 2 April, US 10-year bond yields rose on balance by 45 basis points to around 4.45%. In between, it even briefly reached around 4.50%. The main reasons were rising inflation fears due to US trade tariffs as well as a risk premium that gradually crept into US assets such as bonds. The same risk premium was also the cause of the sharp depreciation of the US dollar during the period. The recent fall in US interest rates to around 4.30% mainly reflected increased growth fears in bond markets.

In contrast, the German 10-year rate fell sharply since its peak of almost 2.90% in March, following the announcement of Germany's ambitious investment plans, to currently around 2.60%. This decline was partly caused by a certain flight to safe financial assets, in this case German government bonds, as a mirror image for the decreased confidence in US government securities. The fall in German real bond yields over that period was much more limited than that of nominal interest rates, however. This suggests that the pronounced fall in German nominal interest rates was also driven by the sharply declining inflation expectations for the near future for the eurozone.

We forecast no further decline in US bond yields. In the US, growth fears and the rising risk premium for US assets are likely to keep each other roughly balanced in the coming quarters, leading to a stabilisation of interest rates around current levels. From the end of 2025, US interest rates will then likely gradually rise, when the main growth fears will be behind us and the effect of the increased risk premium will dominate. By the end of 2026, interest rates are therefore likely to reach the 4.50% level. Based on economic 'fundamentals', that seems a justified level.

German 10-year bond yields will fluctuate in a band around current levels for the rest of 2025. A fundamental upward pressure on the still artificially low term premium in German interest rates and the effects of the gradual roll-out of ambitious investment programs are offset by downward pressure due to increased capital flow into safe assets. From early 2026, the investment programs, and associated bond issues, will reach cruising speed. From then on, German 10-year yields will gradually rise towards 2.80% by the end of 2026, according to our expectations.

We expect that international investors' increased distrust of the US will be structural. Hence our expectation is that the US dollar will weaken further to around 1.20 USD per EUR by the end of 2025 and to 1.22 USD per EUR by the end of 2026.

Trade tariffs only temporarily increase interest rate spreads

The announcement of so-called ‘reciprocal’ trade tariffs by the US in early April caused a sudden and sharp jump in European yield spreads against German Bunds, both on intra-EMU government bonds and on corporate bonds. The main reason was the general jump in risk aversion in financial markets. Fears about the negative growth impact of that measure and thus the creditworthiness of the debtors involved may also have played a role. However, there was a general jump in risk premiums, without a debtor-specific cause.

However, interest rate spreads fairly quickly resumed a downward normalisation trend. That normalisation gained momentum after the announcement of tariff suspensions for a 90-day period. In the case of intra-EMU government bonds, the stabilising effect of the ECB's Transmission Protection Instrument continues to play its role.

For intra-EMU sovereign spreads, we maintain our scenario that these spreads passed their peaks and could gradually narrow further over the course of this and next year.

All historical quotes/prices, statistics and charts are up to date, up to and including May 12, 2025, unless otherwise stated. Positions and forecasts provided are as of May 12, 2025.