Is EU trading its dependence on fossil fuels for a dependence on critical raw materials?

For years, the EU counted on cheap fossil fuels from Russia to meet its energy needs. In 2022, after Russia invaded Ukraine, the bloc suddenly found that it had put too many eggs in one basket when it came to its energy supply. This not only undermined EU support efforts for Ukraine, it also caused an energy crisis with skyrocketing energy prices that made their way to the rest of the economy. The EU has since made significant progress in reducing its dependence on Russian fossil fuels. The same overdependence issue exist for critical raw materials, which are essential building blocks for the green and technological transitions and for the defense industry. The EU has woken up to this reality and is taking some important steps to diversify its supply of critical materials. Whether the EU will be able to successfully reduce its dependence on a few countries, with China as the most important example, will become evident in the coming years.

Fossil fuels as a weapon in the war in Ukraine

Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022 made painfully clear how dependent the EU was on cheap Russian fossil fuels. The high reliance on Russian gas especially, weakened the EU's ability to impose sanctions on Russia in the beginning of the war as there were fears that Russia would cut off its gas supply in response to European sanctions.

Diversifying gas imports in the short term proved difficult because the infrastructure to import LNG was inadequate to compensate for pipeline gas supplies from Russia. Because of this, the EU launched its REPowerEU plan in 2022, a plan to reduce dependence on Russia for fossil fuel supplies, reduce energy consumption and increase the share of renewable energy in the energy mix.

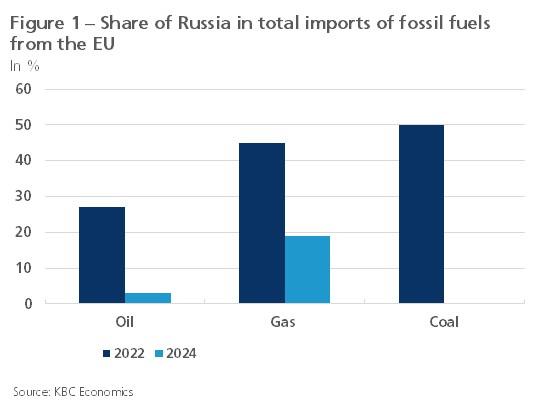

The REPowerEU plan, combined with specific sanctions against Russia's fossil fuel industry, has successfully reduced fossil fuel imports from Russia in recent years (see Figure 1). Between 2022 and 2024, the share of Russian coal in total coal imports was reduced to 0% and the share of Russian oil in total oil imports fell to 3%. Gas imports more than halved but were still 19% in 2024.

One sidenote here is that these data do not take into account the possible circumvention of sanctions by oil deliveries carried out by the Russian shadow fleet as there are now official figures on this. There is, however, evidence that the main destinations for these shadow fleets (India, China and Turkey) are outside the EU.

In 2025, the EU published a roadmap to further reduce energy supplies from Russia. The ultimate goal is to stop all direct and indirect imports of gas and oil by the end of 2027. By March 1, 2026, all EU countries must prepare an energy diversification plan with detailed measures and milestones for phasing out Russian fossil fuels.

Other (and bigger) dependencies lurk around the corner

An important lesson from the war in Ukraine for the EU is that overdependence on just a handful of counterparts can have dangerous consequences. Yet the bloc has falling into this trap again with the imports of critical raw materials like aluminum, lithium, boron, cobalt, graphite copper and tungsten. These raw materials are critical for greening, for strategic technologies in aerospace and defense, and for broader industry. Critical raw materials can be found all over the world, but mining is not always economically interesting and refining activities are mostly in the hands of just a few countries. For example, the EU gets 100% of its heavy rare earths from China, 98% of its boron from Turkey and 71% of its platinum from South Africa.

Even if the EU is not directly involved in a conflict with a major supplier of critical raw materials, it can still be impacted. This was recently the case in the tariff war between China and the US. In retaliation to the trade tariffs Trump wanted to impose on Chinese imports, the Chinese government decided in April 2025 to restrict exports of critical minerals and magnets, and to do so to all countries to prevent the materials from entering the U.S. via third countries. Last week, China again announced export controls on magnets and rare earths. The timing of this new decision is not coincidental because negotiations are scheduled to take place between the U.S. and China later this month. Under the new rules, foreign companies need permission from the Chinese government to export magnets containing even traces of rare earths mined in China, or produced using Chinese extraction, refining or magnet production technology. And once again, the new policies are aimed at the whole world, not just the US.

The EU's demand for critical raw materials has already risen sharply in recent years and this trend will continue in the coming years. Two key EU challenges, rebuilding its defense apparatus and combating climate change, will play an important role in this. A 2023 advisory report commissioned by the European Commission and prepared by the Joint Research Center shows that European demand for aluminum could increase fivefold by 2050 from 2020 levels (see Table 1). For copper, almost a tenfold increase is expected over the same period, and for nickel and lithium, demand in 2050 could be 15 and almost 20 times higher, respectively, than in 2020.

Table 1 - Expected increase in demand for critical materials (in %)

Raw material |

Expected increase in demand |

|---|---|

Aluminium |

539 |

Copper |

923 |

Nickel |

1506 |

Cobalt |

366 |

Lithium |

1983 |

Source: KBC Economics based on JRC

First timid steps in the right direction

For some time now, the EU has been aware of the great and rapidly growing importance of critical raw materials and the practical and strategic implications of dependence on other countries for them. The bloc has therefore already concluded more than a dozen commodity agreements with third countries, including Canada and Kazakhstan, since 2021.

Even more important than the bilateral agreements is the Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA), which the EU adopted in 2024. This regulation aims to increase and diversify the supply of critical raw materials to the EU, strengthen circularity and support research and innovation in resource efficiency and the development of alternatives. To achieve these goals, the regulation imposes minimum targets by 2030, including on the percentage of raw materials to be extracted within the EU (10%), the percentage of raw materials consumed to be processed within the EU (40%), the recycling of raw materials (25% of annual consumption must be made up of raw materials recycled in the EU) and the origin of raw materials (for any strategic raw material, no more than 65% of annual consumption in the EU must come from a single third country, at any stage of processing).

The law also includes provisions to reduce administrative burdens (including by providing a single coordination point for permits in each EU country) and to shorten permit procedures (27 months for extraction permits and 15 months for processing and recycling permits) for critical raw material projects in the EU. These measures should help speed up the overall lead time between the application and the operationalisation of projects. A much needed part of the puzzle given that it usually takes 10 to 15 years for extraction projects to get underway in the EU.

CRMA in action

Earlier this year, the EC approved for the first time a list of 47 strategic projects to increase domestic strategic resource capacity. The projects are spread across 13 EU member states: Belgium, France, Italy, Germany, Spain, Estonia, Czech Republic, Greece, Sweden, Finland, Portugal, Poland and Romania.

The 47 strategic projects require a total investment of 22.5 billion euros, in which the European Investment Bank (EIB) will have an important role to play. Earlier this year, the EIB approved a new strategic initiative on critical raw materials to strengthen its role as a key provider of financing (2 billion euros in 2025) and advisory support for projects across the value chain within and outside the EU.

In addition to the 47 strategic projects within the EU, the EC also designated 13 critical raw material projects outside the EU as strategic projects in June this year. Taken together, these projects are expected to require about €5.5 billion in investments.

Some challenges

The CRMA is an important initiative to reduce the EU’s overdependence on a handful counterparts, but there are a few caveats. On the one hand, the deadline is very short. Even if permit procedures can be shortened because of the urgency of the CRMA, it is rather unlikely that capacity can be sufficiently expanded by the 2030 deadline to meet the ambitious CRMA target.

The financing of these projects is also being questioned. The EIB has stepped up to the plate but additional private capital will be needed. Commodity prices are often volatile, which may deter international investors. Meanwhile, most European governments are already struggling with high debt levels, which could limit the availability of public financing for CRMA projects. In addition, the mining and processing of critical raw materials requires high energy consumption, which makes the EU less attractive compared to other locations because of the higher energy costs in EU countries. Stricter environmental laws and more ambitious emission reduction targets in the EU can also hinder these often highly polluting projects.

We can only hope that, despite all obstacles, the EU will succeed in diversifying (and partly taking over) its supply of critical materials. After all, recent history with Russia has proven that unilateral dependencies are dangerous. The framework is in place, now it’s time for the implementation phase.