What the US social safety net can learn from Covid-19

Compared to many other wealthy economies, the United States stands out for its relatively bare-bones social safety net. The Covid-19 pandemic and its disastrous impact on the US labour market threatened to expose and exploit the vulnerabilities of that minimal system. Fortunately, since the outbreak of the pandemic, the US government has stepped in with unprecedented relief measures that include, among others, enhanced unemployment benefits and direct money sent to individuals under a certain income threshold. While the precise impact of all of these measures on the economy will need to be studied in detail in the years to come, the stimulus measures that focused on relief for individuals and households likely prevented many families from falling into (or further into) poverty last year. Given the relatively high levels of income inequality and poverty in the US compared to other advanced economies, the US should learn from its foray into an expanded (and better performing) social safety net. Even after the pandemic subsides, a permanent enhancement of social policies can help the US combat poverty and inequality within its own borders.

Weak social spending and high poverty

The social safety net in the US is known for its minimal structure compared with other advanced economies. Figures from the OECD on social spending illustrate this point: the US spends 0.14% of GDP on unemployment benefits compared to 0.59% for the OECD as a whole (Belgium, meanwhile, is at the high end of this indicator, spending 1.82% of GDP)1. Spending on family benefits is also particularly low in the US (0.6% of GDP) compared to the OECD (2.1% of GDP). Furthermore, in 2019, over 55% of Americans were covered by health insurance provided by their employer (source: US Census Bureau). This adds another vulnerability beyond income loss for those who become unemployed.

A weaker social safety net may partially explain the relatively higher poverty and income inequality in the US compared with advanced economies. Among OECD countries, the US had the second highest poverty rate as of 2017 at 17.8% (notably, the US Census Bureau indicated a much lower poverty rate of 10.5% in 2019, with the difference likely stemming from the definition of the poverty line: the OECD uses half the median household income, making it comparable across countries, while the Census Bureau’s thresholds vary based on family size and composition). Income inequality, as measured by the World Bank’s estimate of the GINI index, is also much higher in the US relative to other advanced economies and has risen notably since the mid-1970s.

A significant government response

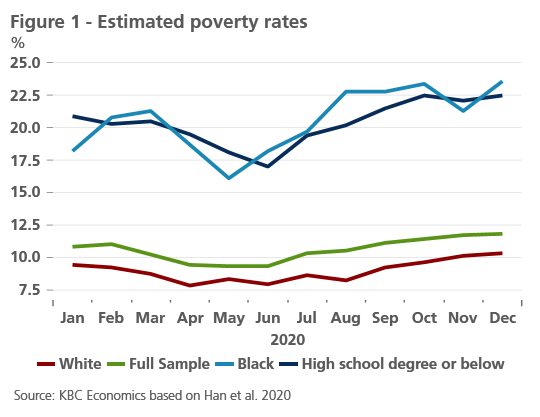

Given the structure of the US labour market, healthcare system and social policies in general, the Covid-19 crisis had the potential to send poverty in the US skyrocketing. A new monthly series based on Census Bureau data, however, suggests that the poverty rate in the US increased by only 1 percentage point between January 2020 and December 20202. It is important to note, however, that poverty rates for Black Americans increased 5.4 percentage points over this time horizon, highlighting that the already existing racial disparities in wealth and income in the US were further exacerbated by the pandemic. What is particularly striking though, is the evolution of poverty rates throughout 2020: the percentage of individuals who fell below the poverty line actually declined in April and May for the full sample as well as for Black Americans and Americans without a college degree (figure 1).

This decline in poverty happened despite a sharp jump in the unemployment rate to 14.8% in April 2020 (from 4.4% the month prior) and has been attributed to the passage of the CARES act in March 20203. Indeed the reduction in poverty coincided with the government sending out stimulus checks of up to $1,200 for individuals with income under a certain threshold and an additional $500 for qualifying children. The CARES act also enhanced unemployment benefits by $600 per week (on top of regular state unemployment benefits). The result was that personal disposable income rose 15% from March to April, with government transfers in particular doubling. At the same time, consumer spending started to recover after taking a cliff dive between the start of 2020 and April 2020.

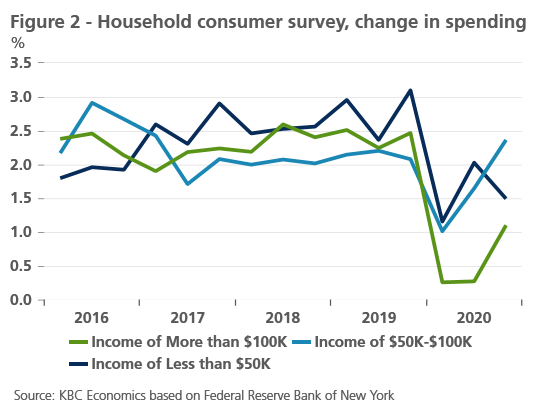

Perhaps unsurprisingly, consumer surveys show that the rate of spending bounced back first among lower-income and middle-income households, while spending growth among households making more than $100,000 didn’t start to recover until August 2020 (figure 2). Hence, there is some evidence that the targeted direct checks and increased unemployment benefits not only helped lessen the poverty rate, but also helped spur consumer spending. Conversely, as the additional $600 unemployment benefit expired in July, and with the stimulus checks at the time being only a one-off payment, spending among those making less than $50,000 declined again between August and December 2020. At the same time, the poverty rate started to rise once again by the middle of the summer.

The US government has since passed an additional relief bill worth $900 billion in December 2020 and is working on another legislative package which could be up to $1.9 trillion (for more details, see KBC Economic Opinion: US backs away from dreaded fiscal cliff). These additional government measures, which include (or are expected to include) further direct payments to individuals, an extension of enhanced unemployment benefits, and an expansion of the child tax credit, are an important way to help households still struggling as a result of the pandemic. A more permanent expansion of the social safety net, however, if structured right, could help alleviate poverty, reduce inequality and boost spending among lower-income households. This, of course, would require adjustments to the US budget elsewhere, whether through raising taxes or adjusting spending, but overall, the US government should look beyond the horizon of the current crisis and learn from the success of its temporary measures.

1 This lower spending on unemployment benefits also generally holds when differences in the unemployment rate are considered.

2 Han, Meyer and Sullivan, Real-time Poverty Estimates During the COVID-19 Pandemic through December 2020, (2021).

3 Han, Meyer and Sullivan, Income and Poverty in the COVID-19 Pandemic, (2020)