The macroeconomic (ir)relevance of central banks’ profits or losses and their equity positions

On 30 March 2023, the National Bank of Belgium (NBB) communicated that in 2022 it made a loss of 580 million EUR. In its market notice of 29 March 2023, the NBB also refers to a base scenario (with still very large uncertainty) in which, if it materialises, the NBB may post cumulative losses of about 10.8 bn EUR during the next 5 year period.

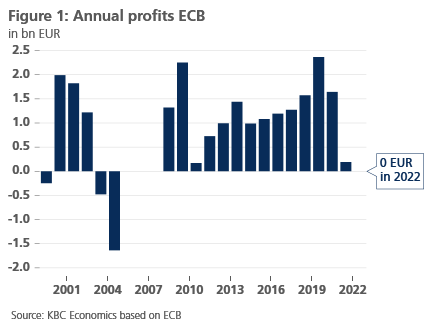

In the same context, on 23 February 2023, the ECB released its financial statement for 2022. It stated that, after a profit of 0.2 bn EUR in 2021, there was zero profit in 2022, after the release of 1.6 bn EUR from previous provisions for financial risks. This means that the ECB ran an underlying loss in 2022 of close to 1.6 bn EUR. As a result there is no profit distribution to the euro area national central banks (NCBs), the shareholders of the ECB.

Already in September 2022, Dutch central bank (DNB) president Knot was the first to inform its Minister of Finance that DNB would incur a loss for 2022, a risk that the DNB had already warned of in its previous annual reports. The mentioned losses are mainly due to increased remuneration paid to commercial banks’ reserves with the central bank, as a result of the sharp rate of the ECB’s policy rates in 2022 (of the deposit rate in particular). Shortly after, the National Bank of Belgium (NBB) announced that this would also be the case for the NBB. As mentioned above, this was confirmed in March 2023.

In some cases and depending on specific accounting procedures, central bank losses can be sizeable and even result in negative equity. This raises a number of important economic questions. First, what are the causes of central banks losses and are they of a temporary or more permanent nature? Second, are such losses a problem from a macroeconomic policy point of view? And third and more fundamentally, do central banks actually need positive equity to fulfil their mandate?

Determinants of central banks’ Profit and Loss (P&L) accounts

The P&L account of a typical central bank is determined by the composition of its balance sheet and the associated risk exposures. A typical central bank holds domestic and foreign currency securities and claims on the asset side of its balance sheet. This is largely funded with banknotes in circulation and commercial banks’ reserves with the central bank (base money), both on the liability side of the balance sheet.

The composition of the balance sheet also determines the main drivers of central banks’ P&L as well as their relative impact:

· interest and other income earned on assets acquired and paid on liabilities (mainly bank reserves)

· changes in asset valuations caused by e.g.

o changes in bond yields

o changes in the gold price

o foreign exchange operations and revaluations of international reserves in the case of central banks (of mostly small open economies) with large FX reserves, such as the Swiss National Bank and the Czech National Bank

o changes in asset prices in general (e.g. affecting the Bank of Japan, whose Quantitative and Qualitative Easing (QQE) portfolio includes equity and real estate exposures)

· impairments in assets, e.g. in the ECB’s Corporate Sector Purchase Programme

· (net) operating expenses

Bank reserves are by far the dominant category on central banks’ liability side. As large-scale asset purchases, introduced with the initiation of non-conventional monetary policy operations, were mainly funded by newly created (renumerated) bank reserves, this liability component grew exponentially.

Against this backdrop, the P&L is now predominantly determined by the relative changes in interest receipts and payments on the asset and liability side of the central banks’ balance sheet. Changes in the interest rate structure can effectively and materially impact the P&L accounts of central banks. In the context of abruptly increasing interest rates, central banks’ net interest rate income suffers, as duration mismatches lead to higher renumerations on bank reserves (increasing costs), while interest income from long-term assets (mainly bonds) remain fixed at low levels.

Next to interest rate income, other factors impact the P&L-reporting. Although eventually less material in the long run, , a crucial factor in the year-to-year reporting of central banks’ P&L (see Figure 1 and 2) are the accounting practices used in the intermediate recognition of asset valuation changes.1.

Central banks use different accounting procedures to address this. In a first approach, fair value changes go directly to the P&L (‘mark-to- market’). This method is used by e.g. the RBA and the BoE. In the Eurosystem, gold, foreign exchange and financial instruments (including part of the securities holdings that are not purchased for monetary policy purposes) are revalued at market rates and prices at the end of each quarter. However, securities in monetary policy portfolios are not valued ‘mark-to-market’ but on an amortised cost basis2. An alternative approach is to recognise changes in market values only when assets are sold (historic cost accounting). This system reduces volatility from asset valuations and is used by the US Fed, even if unrealised valuation changes are disclosed for transparency reasons, but not in the formal recognition in reported income.

Whether recognised in the short term or not, as noted above, the declining or even negative annual profits of central banks are fundamentally caused by the turnaround of monetary policy in the course of 2022. It marked the end of a monetary policy regime characterised by ultra-low (or even negative) policy rates, interest receipts on assets purchased during large-scale asset purchases, as well as upward asset (bond) price revaluations as a result of these QE programmes. In this period, central banks made substantially higher-than-normal profits, part of which were used by the Eurosystem (in particular by the NCBs) to build-up provision. According to the ECB, the Eurosystem (ECB and NCBs combined) made sizeable cumulative profits of approximately 300 bn EUR between 2012 and 2021 (before tax and general provisions).

However, from 2022 on, increasing policy rates led to higher remunerations of central banks’ liabilities (the commercial banks’ reserves), while the end of QE and the start of Quantitative Tightening led to downward asset (bond) price revaluations. The combined effect is a significant drop of central banks’ net interest income.

This drop in net income (resulting even in losses) is likely to be a temporary phenomenon. The return to a positive interest rate environment is likely to eventually support the Eurosystem’s profitability again in the medium term (see also ECB communication and the already mentioned NBB press release). In other words, the current central bank losses are the inevitable mirror image of the previously frontloaded central bank profits made in times of QE, with low or even negative remuneration of newly-created bank reserves and interest income from the securities purchased. Once the current normalisation phase is completed, a return to more normal interest rate term structures with relatively stable net interest income for central banks is likely.

2. Do losses matter ? Why central bank finances are unique

Are central banks’ losses a cause for concern ? More general, what is the economic relevance of the concepts of central banks’ P&L and equity position ?

It should be noted that central banks are in general public institutions, with clear economic policy mandates in terms of price stability, and in some instances secondary economic objectives and financial stability. Profitability itself is not an objective and, if it occurs, is only a side-effect of policy actions the central banks take in order to pursue their actual policy objectives.

For these specific reasons, the concept of (in)solvency, which applies to ‘normal’ firms, does not apply to central banks, nor do the usual regulatory minimum capital requirements. This is due to the central banks’ authority, and monopoly, to create banknotes and reserves as they see fit to achieve their policy mandates. In principle, central banks are always able to issue sufficient currency to fund any liability they may have. Hence technically they cannot become insolvent (at least not in their own currency). Therefore, losses and negative equity do not directly affect the ability of central banks to operate effectively (BIS bulletin No. 86).

The only practical constraint is that any such currency issuance must remain consistent with central banks’ policy objective of price stability (see staff memo of the Swedish central bank). This constraint is satisfied under most plausible economic scenarios. Hence, from an economic point of view, central banks do not normally need to be recapitalised by their fiscal authorities (and hence by taxpayers) if they report losses or even negative equity.

But central bank losses are not economically inconsequential either, however. There is one channel through which central banks’ P&L does have a direct impact on macroeconomic policy in general, and on fiscal policy in particular. As public institution, central banks typically transfer part of their profits to their respective fiscal authorities, after relevant rules with respect to the build-up of loss-absorbing buffers are implemented. This is a reflection of the fact that central banks are part of the consolidated public sector balance sheet. In the case of the ECB, these ‘shareholders’ are the national central banks (NCBs) participating in the euro area. These NCBs in turn transfer most of their respective net incomes (after e.g. the build-up of appropriate buffers) to their national fiscal authorities.

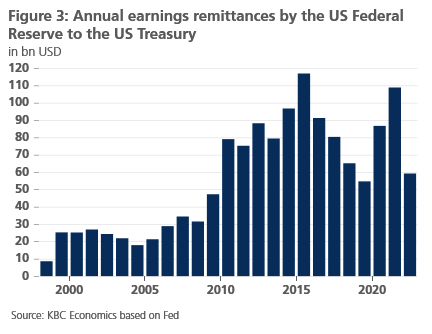

This financial flow means that negative central bank profits do have real economic implications by reducing financial resources for fiscal policy. This may well lead to political controversy, but any such debate is conceptually separated from the issue of central banks’ solvency or financial health. Moreover, it should be noted that the lower (or even negative) remittances to the national Treasuries are the mirror images of the previously higher-than-normal frontloaded remittances during times of ultra-accommodative monetary policy (see e.g., Figure 3 for the US). This is part of the normalisation process of monetary policy.

In any case, providing a source of revenue for the fiscal authorities is not the objective of a central bank. They exist to deliver on their mandate, which in most cases is price and financial stability. Central bank losses (or even temporarily negative equity) as such do not compromise central banks’ ability to fulfil such mandates.

The mechanism of central banks’ P&L and balance sheets is a complex issue, and not always transparent. Therefore, central banks’ communication to the general public, explaining the causes of potential losses and their exact economic-financial relevance (or lack thereof), is extremely important. By communicating clearly, central banks can avoid misperceptions and uncertainty, and hence preserve their most valuable asset, which is their credibility to deliver on their statutory monetary policy mandate.

1 In case of the euro area, Figure 1 refers to the ECB only, i.e. not including the national central banks (NCBs) in the euro area, which together with the ECB form the Eurosystem.