Turkey: new beginning ?

Turkey is one of the few countries to have posted positive economic growth in 2020. A strong expansion, however, came at a cost as credit-driven growth exacerbated underlying vulnerabilities and triggered a steep fall in the lira. To avoid a full-blown currency crisis, Turkey made a pronounced shift to a more orthodox economic policy, reflected by a sharp tightening of monetary policy under the central bank’s new technocratic leadership. Coupled with hawkish forward guidance, this has been welcomed by financial markets, prompting a strong comeback of the lira. Nonetheless, we remain less optimistic about Turkey’s policy shift, mainly due to its unchanged institutional set up. Hence, we see a significant risk of a derailing of the latest effort if, for example, tight financial conditions prove politically too costly as seen in the past.

The Turkish economy has recovered at a remarkably rapid pace from the pandemic. Following a sharp economic contraction in the second quarter, the economy surged in the latter half of 2020, despite deteriorating virus dynamics and renewed lockdown measures in place . For the full year, real GDP expanded by 1.8%, which made Turkey one of the very few major economies to have posted positive economic growth last year.

Strong growth exacerbated underlying vulnerabilities

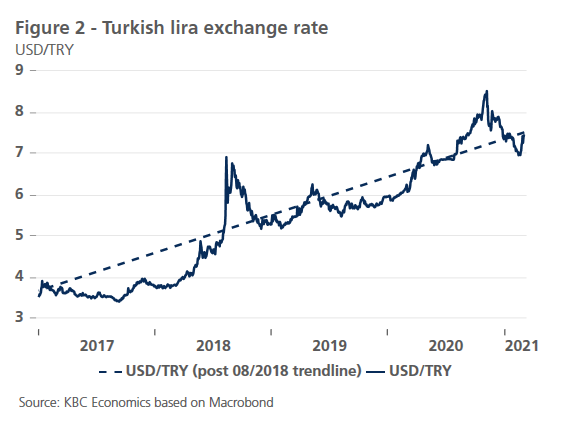

Such a strong expansion, however, came at a cost. Since the beginning of the pandemic, the authorities have relied less on standard fiscal and monetary policy support to maintain activity compared to regional peers. Instead, the government engineered a rapid credit boom, bringing domestic lending growth to 100% (annualised 13-week average) in August 2020. The credit-driven growth exacerbated the country’s underlying vulnerabilities, and led to rising inflationary pressures, a sharp widening of the current account deficit, as well as a reversal in capital flows. Coupled with depleted foreign reserves, this all contributed to a steep fall in the lira to the all-time low of 8.50 USD/TRY, pushing the Turkish economy to the brink of yet another currency crisis.

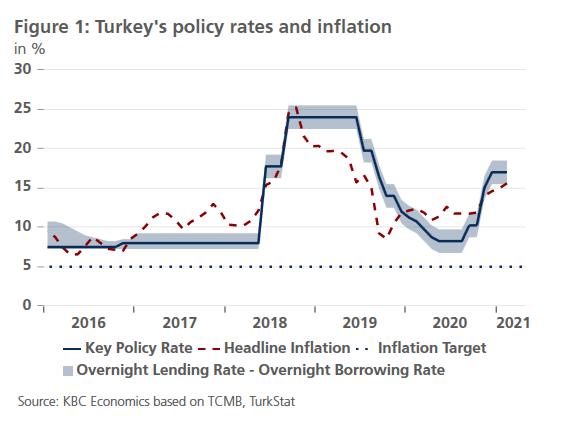

Against this backdrop, Turkey made a pronounced shift to a more orthodox economic policy in November 2020. As a first step, President Recep Erdogan replaced both the governor of the central bank and the finance minister with more technocratic leadership. Soon afterwards, Turkey’s central bank (TCMB) delivered an aggressive monetary policy tightening, hiking the one-week repo rate from 10.25% to 17.00% in the space of two meetings (figure 1). Furthermore, under Governor Agbal, the central bank has markedly simplified its monetary policy framework (e.g. moving to the one-week repo rate as the main funding tool) to provide more transparency and predictability. Importantly, this included the unwinding of the ad-hoc regulatory measures, which resulted in a significantly weaker credit impulse to the economy.

Coupled with hawkish forward guidance from Governor Agbal, the policy shift has helped increase credibility and significantly improve market sentiment. In financial markets, this has been reflected by a fall in Turkish risk premium and a turnaround in short-term portfolio inflows. At the same time, the Turkish lira has shown a strong comeback (though from very low levels, suggesting a mean-reversion rather than a structural strengthening), having been among the best performing emerging markets currencies recently (figure 2). Moreover, there are some initial signs that dollarization has slowed down in the last months, a positive sign that locals may start to trust the lira again.

Institutional weaknesses cast a shadow on a policy shift

Nonetheless, we remain less optimistic about Turkey’s policy shift than markets. This is due to the unchanged institutional set up which casts a shadow on the sustainability of the orthodox policy mix. In other words, with highly centralised institutions, the latest effort could be easily derailed, if, for example, tight financial conditions prove politically too costly as seen in the past.

Looking ahead, Governor Agbal reiterated that monetary policy would stay tight until the ambitious 5% inflation target – consistently missed since 2011 – was reached in 2023. Indeed, keeping real rates higher for longer (at least until inflation expectations have become well anchored) is, in our view, the best strategy to rebuild the credibility of the central bank, as was the case after the 2001 financial crisis. With the political constraints on the TCMB still in place, there is, however, no institutional assurance that the central bank will be able to maintain a ‘tighter for longer’ monetary policy stance.

Overall, we believe that President Erdogan’s green light to an orthodox policy mix will be maintained for some time, setting a stage for a reduction of existing macroeconomic imbalances. At the same time, there is now room for rebuilding buffers such as depleted foreign exchange reserves. However, we do see a significant risk of a reversal of this new policy course, in particular with the new election cycle approaching in late 2022. This would make the recent policy shift less a resemblance of the success story seen in the aftermath of the 2001 economic crisis, and more akin to the period after the 2018 currency crisis when the credibility-building effort was ultimately derailed.