Pandemic challenges the Polish convergence story

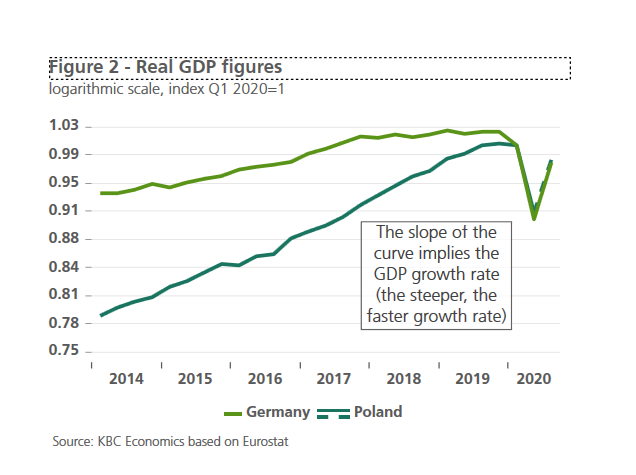

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Polish economy was rightly considered a European economic tiger. On the back of ongoing strong real convergence dynamics, the country enjoyed robust real growth, allowing it to withstand all European recessions. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has changed this rosy picture as the Polish economy now shares the same fate as its suffering neighbouring economies. Moreover, the second wave of the pandemic has hit Poland very hard and its economy risks another decline in the last quarter of this year.

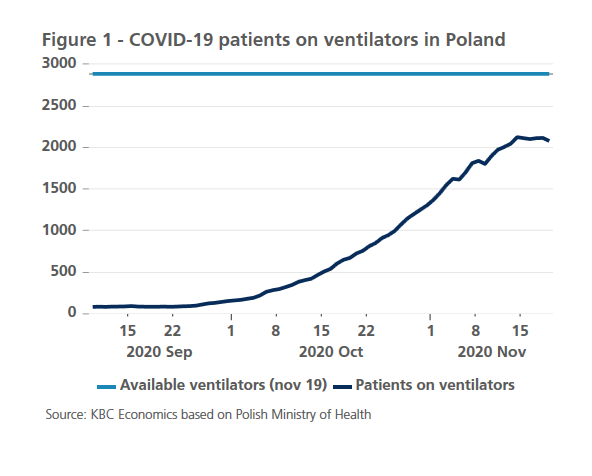

During the Great Financial Crisis of 2008 - 2009, the Polish economy was the only EU-economy that managed to avoid a recession. It has not been that lucky during the coronavirus pandemic and is now witnessing its first recession since 1991. Unfortunately, this is not the only bad news. Poland, like many other European economies, now faces a second wave of the pandemic. And this wave could hit the economy particularly hard, especially given that the relatively good third-quarter results that suggested that the worst of the pandemic was over for Poland. With the arrival of autumn, however, the number of Covid-19 cases started to increase, while the Polish authorities – as many others - only responded with a lag to these developments and only by a gradual tightening of quarantine measures. As a result, Poland now faces problems which the country managed to avoid during the first pandemic wave in the spring: overloading of the healthcare system’s capacity due to the large number of hospitalised patients. A large portion of these patients developed serious health problems and required ventilators, a necessary healthcare device which has not been readily available in Poland. As a consequence of rapidly increasing numbers of ICU COVID-patients (and related deaths) , the Polish government was forced to follow other countries – such as the Czech Republic- in imposing a new (semi-)lockdown.

Clearly, the implemented quarantine measures in Poland, including the closure of most of shops and all restaurants until 29 November, will cause damage to the economy (particularly to services) in the last quarter of the year. Currently the pending question is whether or not the current development of the pandemic will allow for Poland’s shops and restaurants to be reopened before Christmas, as indicated by statements of some Polish politicians. In such case – and under optimistic hypotheses - the second downturn in the Polish economy would be limited to the fourth quarter, with the prospect of a strong recovery in the first quarter of next year.

Unfortunately, our view of the pandemic developments in Poland do not confirm this optimistic scenario. In our opinion, the Polish government will have to be very cautious in easing restrictive measures in order not to risk a rapid onset of the third wave of the pandemic. On the one hand, it is true that the reproductive number - the R-number - in Poland has been trending favourably recently, as it has been pushed below 1. At the same time, however, the number of new COVID-positive cases in the total number of tests performed – the positive rate - is extremely high (around 50%). This high rate of positive COVID cases may indicate that the infection rate in Poland is several times higher than indicated by the current number of confirmed cases. In this situation, premature easing of restrictions would be a big risk, as the healthcare system could be quickly overwhelmed by a high and increasing number of seriously ill patients in ICUs. At the same time, it is obvious that in such circumstances, the so-called smart quarantine measures cannot be applied as public authorities lack the means to perform effective tracing of infected people on such a large scale.

These developments could result in an unusual macro-economic situation where complicated pandemic crisis management will not only reduce the performance of the Polish economy below its potential, but it will also push its growth below the GDP growth of neighbouring (advanced) countries. Thus, the pandemic could disrupt - at least temporarily - the real convergence process - a positive phenomenon that the Polish economy has enjoyed for more than the last 25 years. Specifically, taking into account our GDP nowcasts for the fourth quarter, it is possible that Poland will just ‘mirror’ German GDP performance (see the second chart) for three quarters in row (hence, no growth outperformance as was observed before the outbreak of the pandemic). This may not be the only disappointment, as the first quarter of 2021 might be challenging too, especially if the number of hospitalisations stays elevated at the beginning of the next year.

Still, we do not believe that the pandemic disruption to the Polish convergence story will last beyond the first half of 2021, especially if the current positive news about COVID vaccine effectiveness and its deliveries prove to be true. Nevertheless, the recent Polish macroeconomic experience should be taken as a warning that exogenous shocks and government response to them matters. The truth is that in a situation when a huge negative external event hits, the Polish economy can still rely on its own currency, which works as an important shock absorber. A weaker zloty has helped and thanks to its depreciation Poland has now the highest current account surplus in its history. However, just a weaker currency cannot bring the convergence story back on track. In pandemic times, smart and coherent management of government policies which prevent further spreading of the coronavirus will also help to eliminate unnecessary output losses.

Of course, at the end of the day the Polish long-term convergence ambitions will rely on more structural factors. The EU’s final approval of its new seven-year budget with expected huge transfers (and investments) dedicated for the Polish economy is undoubtedly an important factor in that respect. But that is another story...