Economic Perspectives May 2021

Read the full publication below or click here to open the PDF.

- The global economy continues to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic. However, the recovery is not synchronised, showing a number of divergent developments in the major economies. Our outlook is, overall, optimistic given the substantial progress in managing the pandemic with respect to both infection and vaccination rates, which together with sizable fiscal stimulus sets a stage for a strong rebound in activity across the advanced economies over the coming months.

- The euro area economy slid into a double-dip recession as extended lockdown measures took a toll on economic activity in Q1 2021. High frequency indicators nonetheless suggest underlying activity strengthened at the end of Q1, while the latest second-quarter sentiment data point to ongoing momentum. Together with a ramp-up in vaccination campaigns, this adds to our optimism that a strong economic recovery is set to begin in Q2 and strengthen further in Q3 2021. Overall, we expect the euro area economy to expand by 3.9% in 2021 and 4.4% in 2022.

- The US started 2021 on strong footing amid surging personal consumption, driven by the additional support to household incomes from stimulus bills. The combination of the recent fiscal stimulus packages and rapid vaccination, which allows for an ongoing reopening, paves the way for an even stronger boom in Q2. At the same time, while the labour market continues to improve steadily, the disappointing April jobs report highlighted that slack remains elevated. Still, our outlook for the US economy has become somewhat brighter, which is reflected in upgrades of real GDP growth for both 2021 and 2022 to 6.5% and 4.0%, respectively.

- First-quarter GDP figures confirm that China’s recovery and economic normalisation continue. We expect the strong momentum in the Chinese economy to be sustained, as business sentiment surveys for April point to continued strength in both the manufacturing and services sectors. Meanwhile, we continue to expect only a moderate and targeted tightening of the policy stance in China. Due to the slightly below expectation first-quarter GDP figure, however, we have revised down growth for 2021 moderately from 8.5% to 8.3%.

- On the policy front, both the ECB and the Fed maintained unchanged monetary policy in April, reaffirming our view that low interest rates will be sustained for some considerable time. On the inflation front, short-term pressures are picking up on both sides of the Atlantic. Despite a slight upward revision to our euro area inflation projection, underlying price pressures are set to remain moderate over the longer term. In the US, inflation is also expected to rise rapidly in the coming months, significantly due to higher oil prices, but should ultimately remain well-behaved in the longer term.

The global economy continues to recover from the Covid-19 pandemic, as highlighted by the recent releases of Q1 2021 GDP data. The recovery is, however, not occurring in tandem, showing a number of divergent developments across the major economies. To begin with, the US economy started 2021 on strong footing, and is leading the recovery with the post-pandemic boom ramping up. The euro area economy, on the other hand, saw another mild contraction in the first quarter, sliding into a double-dip recession amid headwinds from the winter wave of the pandemic. Finally, China’s growth is now decelerating in sequential terms, which signals that the pace of recovery already peaked last year.

Growth divergence between the US and the euro area

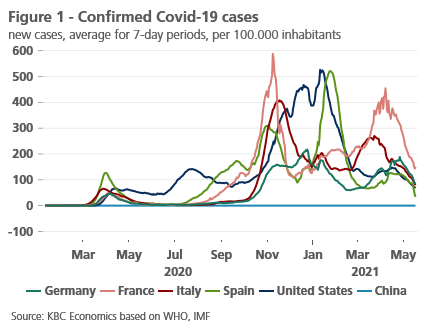

There are several reasons for the stark contrast between the US and the euro area economic performance in early 2021. First of all, the US has made significant progress in managing the pandemic concerning both infection and vaccination rates. The US largely avoided the winter wave of the pandemic with the number of new Covid-19 cases having peaked already in early January 2021 (figure 1). In Europe, strict lockdown measures were meanwhile extended bringing infection rates down markedly by April. While the pandemic now appears to be more under control in Europe, new infection waves in countries such as India or Brazil, as well as the emergence of new variants remain a source of concern.

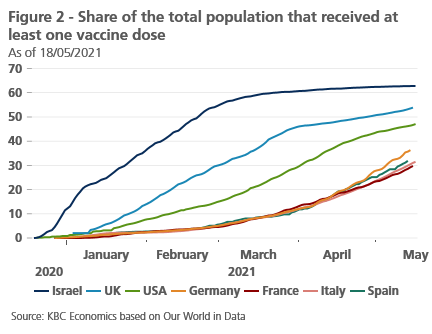

On the vaccination front, the US has made an impressive effort to inoculate its population. On the back of a fast and efficient rollout, the US has now administered more than 250 million doses, meaning that 45% of the population have received at least one vaccine dose (figure 2). Most recently, the pace of vaccination has nonetheless slowed down, which seems to be caused by slowing vaccine demand given the abundant supply. Meanwhile, the European Union’s vaccination campaign got off to a lacklustre start but has recently gained strong momentum. With supply constraints now largely resolved, around 25-30% of the population across the euro area ‘big four’ countries has received at least one dose of a vaccine, suggesting that meeting the EU’s target of vaccinating 70% of adults (corresponding to nearly 60% of total population) by end-June looks achievable.

In addition to pandemic-related developments, the size and speed of fiscal support is another important source of growth divergence between the US and the euro area. The US fiscal response to the pandemic has been unprecedented, so far amounting to USD 5 trillion through measures enacted by Presidents Trump and Biden. Furthermore, President Biden has recently introduced his plan for additional USD 4.1 trillion infrastructure and social spending (see box 1: Biden’s economic agenda). Meanwhile, the fiscal support in the euro area – relying more heavily on the normal operation of automatic stabilisers – has been sizable too, yet on a substantially lower scale, even when including the 750 billion EUR Next Generation EU recovery fund.

Optimistic outlook with lingering risks

Looking ahead, we believe that the euro area is finally on the verge of a strong recovery, following the lead of the booming US economy. Given the massive fiscal stimulus, we maintain our view that the US will outperform other advanced economies in 2021, with growth peaking in the second quarter but remaining strong in the remainder of the year. In the euro area, the economic recovery should begin in the second quarter and strengthen further in the third quarter when we expect the pace of recovery to peak. Outside the advanced economies, we pencil in a robust annual expansion in China, leading the post-pandemic recovery across emerging markets. Some of the least developed economies are, however, likely to experience a delayed and uneven recovery, largely as a result of limited vaccine supply.

Nonetheless, our relatively optimistic economic outlook remains subject to considerable risks, largely related to the evolution of the pandemic and the success of the vaccination campaigns. The emergence of new Covid-19 variants is a major downside risk, in particular should the available vaccines prove ineffective or significantly less effective. The potential for vaccination fatigue is also an important downside risk that could delay reaching the herd immunity threshold. In the face of lingering uncertainty, we maintain three scenarios: the baseline (a gradual recovery strengthening from H2 2021 onwards), to which we attach a probability of 70%; the pessimistic (a disrupted and unsteady recovery) with a probability of 20%; and the optimistic (a sharp and strong recovery already in H1 2021) with a 10% probability.

Box 1 – Biden’s economic agenda

Four months into the Biden presidency in the US, the new administration has laid out, and partially enacted, an ambitious economic agenda. This agenda is focused first on supporting the US economy through the end stage of the pandemic and then on revitalising the US economy by investing in infrastructure and America’s middle class. The agenda has been divided into three separate plans: the already approved American Rescue Plan (1.9 trillion USD), the American Jobs Plans (2.3 trillion USD) and the American Families Plan (1.8 trillion USD).

The American Rescue Plan was passed in March 2021 and mostly focused on short-term, pandemic-related spending and followed up on previous stimulus and relief packages passed under the Trump administration (most notably the 2.3 trillion USD CARES act in March 2020 and a 900 billion USD relief bill in December 2020). It included an extension of enhanced unemployment benefits, tax credits for families, further payments (up to 1,400 USD) to individuals under a certain income threshold, grants to small businesses, and aid to states and local governments.

The other two programs, which are still under negotiation, are focused on longer-term spending and investment. The intent is to bolster the economy for the post-pandemic recovery. The American Jobs Plan, which was put forth in late March, is also known as Biden’s infrastructure plan, as much of the investment will go toward rebuilding and updating American infrastructure. It encompasses over 2 trillion USD in spending spread out over 8 years which amounts to a little more than 1% of (current) GDP per year. The proposed plan would rebuild bridges, highways, ports, and transportation systems. It would also provide funds for replacing or renewing buildings, water pipes, and the electrical grid, and for expanding high-speed broadband access. It also aims to create new jobs in the care sector. Finally, the bill focuses on improving the competitiveness of the American economy, particularly in relation to China, through higher investments in R&D and high-tech domestic manufacturing. Significant as well are the climate initiatives running through the various policy points in the infrastructure plan. This includes making US infrastructure more resilient to climate change and less greenhouse gas emitting, investing in electric vehicle infrastructure, promoting renewable energy, and creating jobs in the clean energy sector.[1]

The American Families Plan complements the jobs plan but focuses more on investing in families and bolstering the middle class. It includes free preschool for three- and four-year old children, two free years of higher education through community college, paid family and medical leave that would bring the US in line with other OECD countries, a program to guarantee that the maximum families spend on child care is 7% of their income and an extension of the tax cuts for low- and middle-income families that was included in the American Rescue Plan.[2] The 1.8 trillion USD of spending and tax cuts in the American Families Plan would be distributed over ten years, amounting to just over 0.8% of (current) GDP per year.

To pay for these plans, the Biden administration has proposed raising taxes on both businesses and higher-income Americans. This includes a partial reversal of the 2017 tax law passed by the Trump Administration, which would raise the corporate tax rate to 28%, and an attempt to close tax loopholes for multinational corporations. The higher taxes on wealthier individuals and families would be brought about by raising the top tax rate back to 39.6% from 37% (another reversal of the 2017 tax law), increasing capital gains and dividend taxes, and closing tax loopholes.

While the US economy will almost certainly face a lower fiscal impulse in 2022 as the enormous short-term pandemic-related spending fades out, these longer-term economic plans (if enacted) could provide a boost to US potential growth and competitiveness, supporting the economy as activity eventually normalizes and moderates into next year and beyond.

A double-dip recession in the euro area

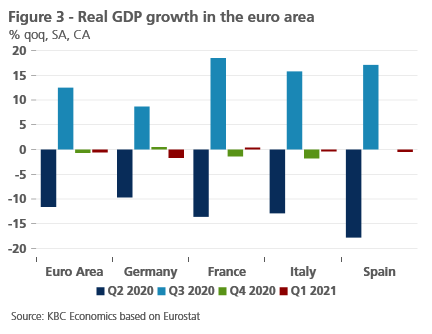

The euro area economy contracted by 0.6% qoq in the first three months of the year, sliding into a double-dip recession as extended lockdown measures took a toll on economic activity. Still, a relatively modest real GDP decline signals ongoing resilience, and shows that households and firms have learned to adapt to mobility restrictions in place. With respect to the pre-pandemic level, the euro area economy remains some 5.5% below the level of activity in Q4 2019, although with significant cross-country differences.

At the member states level, the first-quarter GDP data showed a somewhat mixed pattern (figure 3). France was a relatively bright spot, with growth expanding by 0.4% qoq, supported by domestic demand. The German economy, on the other hand, shrunk by 1.7% qoq, driven by weaker private consumption. Meanwhile, both Italy (-0.4% qoq) and Spain (-0.5% qoq) saw moderate real GDP declines with the former dragged by net exports, while the latter by domestic demand, particularly private consumption.

Looking forward, high frequency indicators suggest underlying momentum in the euro area was strengthening at the end of the first quarter. Moreover, the first batch of second-quarter sentiment data shows improvements in both business and consumer confidence. The composite PMI index increased from 53.2 to 53.8 in April, driven by a surprising gain in services, despite most of the lockdown measures still in place. At the same time, manufacturing activity remains robust, although with signs of supply chain bottlenecks mounting. Similarly, the European Commission’s economic sentiment indicator surged for the second month in a row in April, sending an encouraging signal for activity with broad-based gains.

Together with a ramp-up in vaccination campaigns, this adds to our optimism that a strong economic rebound in the euro area is around the corner. We expect a bounce in activity in the second quarter once economies reopen with a further surge in the latter half of 2021. Along with the release of pent-up demand, the economy is set to be supported by a pick-up in global demand benefiting the euro area exports. Finally, the Next Generation EU recovery fund should start disbursing funds to member states in the second half of 2021, adding momentum to the post-pandemic recovery (see box 2: Reshuffle of the German political landscape heralds new view on fiscal policy).

Overall, we now expect the euro area economy to expand by 3.9% in 2021, marginally down from 4.0% previously assumed. Given the stronger projected growth dynamics in Q2 and Q3 2021, real GDP growth was upgraded from 4.1% to 4.4% in 2022. All this implies that the euro area as a whole is expected to return to the pre-pandemic level of output by early 2022.

Box 2 - Political reshuffle in Germany heralds new fiscal views

The next federal general election for the German Bundestag (Lower Chamber) on 28 September 2021 will probably have far-reaching political as well as economic implications. This election is unique in post-war German political history, since for the first time, it will be held without the sitting Chancellor being a candidate for re-election. Without an incumbent’s bonus, this election is likely to be an open race. Moreover, three instead of two candidates have ambitions for the Chancellorship: Armin Laschet (Christian Democrat (CDU) and prime minister of North Rhine Westphalia), Annalena Baerbock (co-chair of the Green party) and Olaf Scholz (Social Democrat (SPD) and Federal Minister of Finance).

According to the latest opinion polls, the current coalition of CDU/CSU and SPD will not regain an overall majority of seats (see Figure B2.1). This would imply that not only a new Chancellor but also a new government coalition will take over after September 2021.

Based on the latest opinion polls, we can make the following observations. First, it is likely that a political landscape of two ‘large’ parties will emerge, consisting of the CDU/CSU and the Green Party. Recently, the sum of the two parties’ relative weights in the opinion polls has been broadly stable. This implies that a potential coalition between the two parties would obtain a clear and stable majority of votes, at least for the time being. Second, the CDU/CSU lost support in polls in recent months due to the perceived poor handling of the Coronavirus crisis, related corruption charges against some Christian Democratic MPs, and the somewhat chaotic selection procedure of the candidate for the Chancellorship. The Green Party had been the main beneficiary of this shift of voters’ intention, making the Green Party the largest party at this moment. The very latest polls suggest a neck and neck race. Third, the polls suggest that the SPD will be structurally reduced to a small-to-medium sized party, with no realistic option of winning the Chancellorship again in the foreseeable future.

The virtually certain government participation of the Green Party is likely to cause a significant shift in German economic policy. In particular, the new government’s stance towards (green) public investments and towards public finances (objective of balanced budgets, the public debt brake and a European dimension to fiscal policy), is likely to change to some extent. High on the Green Party’s election manifesto is the ecological adjustment of the economy to deal with climate change. To achieve this, the party proposes to use incentives based on higher carbon pricing, reduction of European emission allowances in order to raise their price and fiscal incentives to reallocate private investments. Favourable depreciation rules for ecological and digitisation investments are also part of these proposals. Perhaps more significantly from a macroeconomic policy point of view, the Green Party proposes an annual public investment budget of 50 bn EUR (about 1.5% of GDP), financed by new public debt after a reform of the (constitutionally enshrined) debt brake. This proposal would effectively also abandon the longstanding ‘Schwarze Null’ policy as it currently stands. A reduction of overall existing subsidies is also planned to free up budget resources.

The most likely coalition partner of the Green Party, the CDU/CSU does not have a formal election manifesto yet. This in itself is not unusual since the German Christian Democrats are traditionally not a programme-based party. Policy proposals so far would essentially deliver continuity with respect to the current government and include the digitisation of the education system and the civil service, reduction of bureaucratic obstacles for businesses, and lower (and EU-wide harmonised) corporate taxation. In terms of fiscal policy, the concept of the budgetary balance throughout the economic cycle (‘Schwarze Null’) was promoted by the then CDU Finance Minister Schäuble. The current government has continued to follow that principle (even under SPD Minister of Finance Scholz) and the CDU is likely to want to stick to it, even though earlier this year, senior CDU Minster Braun floated the idea to amend the legal rules governing the federal debt brake.

The most likely main opposition party after the September election, the SPD, is likely to be conservative with respect to the ‘Schwarze Null’ and the debt brake. However, the SPD has far-reaching proposals with respect to a European dimension for fiscal policy. These include further plans for an EU wide unemployment re-insurance and follow-up programmes to the current NextGenerationEU programme (NGEU) (i.e. a ‘Hamiltonion moment’ for the EU).

In sum, the German federal elections in September, with its likely prominent role for the Green Party, will probably mark a clear change in the German political landscape and the traditionally held views about fiscal policy, acceptable debt levels and a more extensive European fiscal policy dimension. New policy initiatives in this direction will become more likely.

The booming US economy

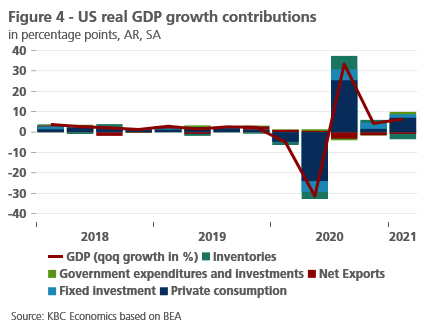

The US economy was off to a strong start in 2021 with real GDP picking up at a 6.4% annualised rate in the first quarter, leaving the output just 0.9% below its pre-pandemic peak in Q4 2019. The strong GDP outturn was largely driven by personal consumption, boosted by the additional support to household incomes from the stimulus bills, including the late-December USD 900 billion Response and Relief Act and the March USD 1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan. Furthermore, activity was supported by business fixed investment, both residential and non-residential, as well as government spending, while net exports and inventories were a drag on growth in the first quarter (figure 4).

The combination of the two recent fiscal stimulus packages and rapid vaccination, which allows for an ongoing reopening, sets the stage for an even stronger boom in the second quarter. The available second-quarter activity data largely confirm the robust pace of the economic recovery with improving consumer confidence and strong business confidence prints. Although the April ISM manufacturing index unexpectedly dropped from 64.7 to 60.7, the latest figure is still solid by historical standards. At the same time, the composite PMI index firmed in April with gains across the sectors, suggesting the momentum in economic activity has continued into the early part of the second quarter.

Against this background, the April jobs report disappointed massively with the US economy having added only 266,000 jobs, significantly less than consensus expectations of 1 million job gains. We find the shortfall in employment relative to expectations difficult to reconcile with much of the recent high frequency data, and it is possible that several transitory influences contributed to the weak jobs report. Overall, the labour market conditions have improved substantially since April 2020 with the unemployment rate down from an all-time high of 14.8% to 6.1%. However, the recent print highlights a challenging path ahead for the US labour market as the slack remains elevated and the economy is still 8.2 million jobs short of pre-pandemic levels.

All in all, our outlook for the US economy has become somewhat brighter, which is reflected in upgrades of real GDP growth for both 2021 and 2022 to 6.5% (from 6.2% previously) and 4.0% (from 3.8% previously), respectively. This implies that the US economy is on track to recover to its pre-pandemic level already during the current quarter. At the same time, we continue to flag upside risks to GDP due to stronger-than-expected pent-up demand from US consumers and further government spending plans.

China’s economic normalisation underway

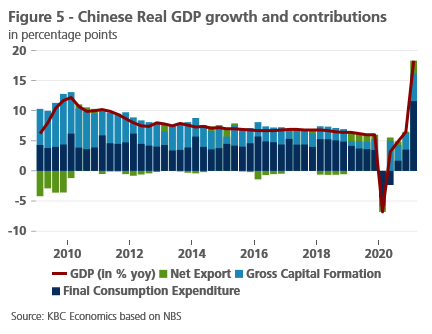

First-quarter GDP figures confirm that China’s recovery and economic normalisation continue. The economy grew 18.3% yoy in the first quarter – an eye-popping figure that reflects the sharp decline registered one year earlier during the most severe period of China’s lockdown (figure 5). The figure was slightly below expectations but still points to a robust, ongoing recovery. Consumption, which lagged in the early part of China’s recovery, contributed 11.6 percentage points to the year-over-year figure, while investment contributed 4.5 percentage points and net exports contributed 2.2 percentage points (driven by strong export growth over the period).

Looking forward, we expect the strong momentum in the Chinese economy to continue, as business sentiment surveys for April point to continued strength in both the manufacturing and services sectors. Meanwhile, we continue to expect only a moderate and targeted tightening of the policy stance in China, with credit growth continuing to gradually slow but policy interest rates remaining stable. Due to the slightly below expectation Q1 figure, however, we have revised down growth for 2021 moderately from 8.5% to 8.3%. Although the vaccination campaign is proceeding relatively slowly compared to other major economies, the still relatively low spread of the virus in China mitigates the risks from this slow rollout.

Central banks set to maintain an accommodative stance

In line with our expectations, both the ECB and the Fed maintained monetary policy unchanged in April, reaffirming our views on the near-term monetary policy outlook. In the euro area, the ECB appears satisfied with the effects of the increase in the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) pace since the March meeting, reiterating its commitment to preserving favourable financing conditions. The Governing Council nonetheless did not offer any guidance on whether the current rapid pace of asset purchases will be maintained in the third quarter. Attention thus turns to the 10 June monetary policy meeting when the ECB is set to reassess the PEPP purchase pace together with the updated staff projections.

Meanwhile, the April FOMC meeting sent the clear message that the Fed is nowhere close to considering starting to taper the current monthly pace of asset purchases. Although economic activity is picking up sharply in the US, the Fed signals that it is prepared to look through higher inflation this year, since it sees such an outcome as driven by transitory factors. At the same time, the central bank maintains its emphasis on the improvements on the labour market, implying that substantial progress toward full employment needs to be achieved to consider tapering. In this respect, the disappointing April employment report will likely take any discussion of tapering off the table at the June FOMC meeting.

Short-term inflationary pressures on the rise

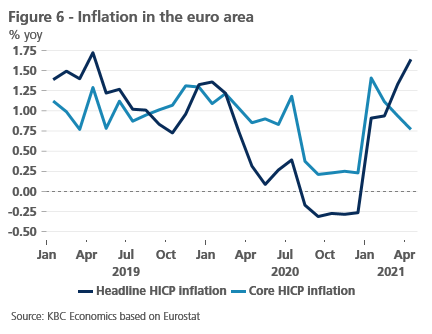

On the inflation front, short-term pressures are strengthening on both sides of the Atlantic. In the euro area, headline HICP inflation accelerated from 1.3% yoy in March to 1.6% yoy in April, largely on the back of strong base effects from higher energy prices (figure 6). Looking ahead, we continue to expect volatile inflation amid a host of temporary and technical factors, including changes to the HICP basket weights and the unwinding of the German VAT reduction. At the same time, we expect headline inflation to pick up further in the coming months, driven primarily by higher oil prices. In addition, mounting supply-chain disruptions and rising input prices in the goods sector represent a further upside risk to near-term inflation pressures. Overall, we have marginally upgraded our inflation outlook by 0.1 percentage point to 1.7% in 2021. A pullback in headline inflation to 1.4% next year is largely a technical development on more stable oil prices. However, it also suggests we don’t envisage a sustained surge in price pressures over the medium to longer term.

Short-term inflationary pressures are picking up also in the US economy with headline inflation picking up much stronger than anticipated from 2.6% yoy in March to 4.2% in April. More importantly, core inflation showed the fastest monthly increase (+0.9%) since 1982 and this boosted the year-on-year metric to 3.0%, the fastest increase in twenty-five years from 1.6% in February. These developments look set to sustain concerns about runaway inflation in the future. We anticipate a further near-term upshoot in headline inflation on the back of a positive base effect from higher oil prices, the unleashing of some excess savings, and to a lesser extent due to some emerging supply-chain bottlenecks translating into higher input prices. On the whole, we have upgraded the US inflation outlook. We now expect headline inflation to pick up to 2.8% (from 2.6% previously) in 2021, before easing somewhat to 2.1% (from 2.2% previously) in 2022.

All historical quotes/prices, statistics and charts are up to date, through 10 May 2021, unless otherwise stated. The positions and forecasts provided are those of 10 May 2021.