Economic perspectives December 2019

Read the full publication below or click here to open the PDF.

- The euro area economy is showing signals of bottoming out. Corporate sentiment indicators in the manufacturing industries are stabilising, although at low levels. The services sector remains resilient and consumers don’t seem to be heavily affected by the global downturn. Hence, economic developments are in line with our scenario of a gradual recovery in quarterly GDP growth dynamics for the euro area. Therefore, our growth forecasts remain unchanged. Despite this optimism our scenario remains very cautious for the short run.

- The main risks to this outlook continue to be the uncertainty surrounding Brexit and further escalations of international trade conflicts even though near term concerns in both of these areas seem to have diminished markedly as a result of a decisive election result in the UK and growing expectations of some progress in US-china trade talks.

- More generally, however, the trade war is now taking place at various front lines. Particularly worrisome is the US threat to impose higher tariffs on typically French products in response to the French Digital Services Tax. This could trigger countermeasures from the EU, leading to a bilateral US-EU trade conflict. Such an escalation would hamper the economic recovery in the euro area.

- Some political risks are popping up again in the euro area as well. French protests against pension reforms, the inability to form a stable Spanish government coalition and some uncertainties surrounding the policy stance of the German Grand Coalition after a new leadership of the SPD was chosen, could all impact sentiment and economic growth.

- The US economy keeps performing relatively well, though the start of Q4 brought mixed activity results. Industrial production remains weak, in line with global developments. US consumers, meanwhile, continue to be optimistic, supported by buoyant labour market developments. Meanwhile Chinese growth keeps slowing down, with on top higher inflationary pressures, mainly caused by higher food prices.

Euro area economy bottoming out

New releases for Q3 real GDP growth in several euro area countries were somewhat better than we expected (e.g. Germany, Netherlands, France). However, some historical GDP figures for the second quarter were revised downward. On balance, the impact on euro area average growth forecasts was only marginal and the general storyline hasn’t been altered. As a consequence, our annual average GDP growth for the euro area as a whole remained unaltered at 1.1% for 2019 and 1.0% for 2020.

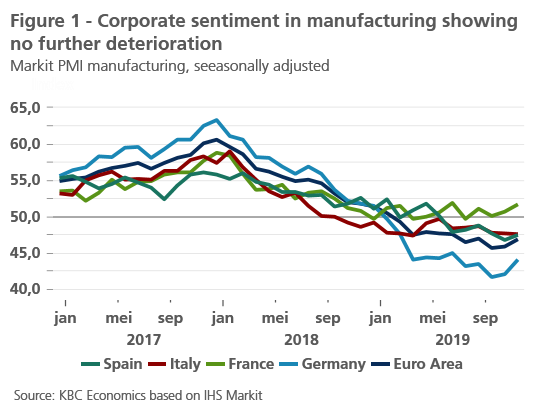

More importantly, it seems that the absolute worst has passed for the euro area economy. Corporate sentiment indicators continue to signal a stabilisation or even some slight improvement in the economic environment. Business confidence in the manufacturing industry remains at low levels, but doesn’t show a further deterioration in most euro area countries (figure 1). The services sector remains quite resilient. Though weakened in past months, consumer confidence is holding up relatively well.

Although recent data on German activity – such as industrial production and new orders in manufacturing – pointed to a rather weak start of the fourth quarter, forward-looking indicators are signalling some cautious improvements. The IFO Business Climate Index slightly rose in November based on improvements in companies’ assessment of the current economic situation and expectations. In particular in the services and trade sector the business climate improved. The increase in the manufacturing PMI in November suggests the tide might be turning. The industrial recession hence seems to be gradually bottoming out. Meanwhile German labour market conditions remain relatively favourable. However, the acceleration in the vacancies fall signals that industrial weakness has taken its toll on the labour market as well.

Based on the aforementioned facts, together with a better-than-expected real GDP growth result in Q3 (+0.1% qoq versus -0.1% qoq expected), fourth quarter growth will likely be lower again (-0.2% qoq) in our view. GDP growth in the third was quarter was underpinned by some one-off factors and hence the latest growth figure is unlikely to be sustainable.

Rocky start of Q4 in US

Though Q3 real GDP growth was revised slightly upwards (from 1.9% qoq to 2.1% qoq annualised), the start of the fourth quarter was rather rocky. Industrial production continued to decline in October even after excluding the effect of the strike at General Motors. However, three of the four main business sentiment indicators have remained in expansion territory. In the light of many domestic and external uncertainties, corporate investments remain rather weak though.

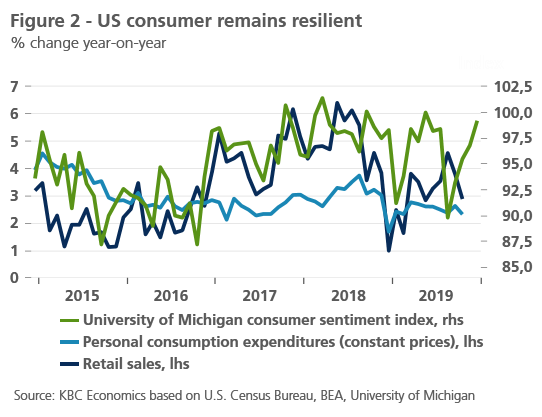

On the positive side, US consumers continue to remain mostly unaffected. Consumer confidence is still at high levels, with the University of Michigan's consumer sentiment index even increasing for the fourth month in a row in December (figure 2). Moreover, personal consumption and retail sales are showing solid year-on-year growth. Private consumption remains underpinned by solid labour market results. The November labour market report surprised on the upside, with stronger than expected jobs growth and upward revisions of job creation in previous months. Since growth support from the consumer side remains solid, we stick to our growth forecasts of 2.3% and 1.7% for 2019 and 2020 respectively.

Box 1 – Preliminary views on the Fed’s ongoing monetary policy strategy review

Washington-based Fed governor Lael Brainard offered her preliminary views on the Federal Reserve’s ongoing review of its monetary policy strategy. The review is to be finalized next year. She started by admitting that she was struck that the effective lower bound (ELB) of policy rates proved to be a severe impediment to the provision of additional policy accommodation initially because of long delays needed to develop consensus and take action on unconventional policy which sapped confidence, tightened financial conditions and weakened the recovery.

In light of the likelihood of more frequent episodes at the ELB, the Fed’s review should advance two goals. First, monetary policy should achieve average inflation outcomes of 2% over time to re-anchor inflation expectations at the central bank’s target. Second, the Fed needs to expand policy space to buffer the economy from adverse developments at the ELB. With regard to inflation expectations, Brainard favours the symmetric approach. This implies supporting inflation a bit above for some time to compensate periods of underperformance. More specifically, she puts forward the idea of “flexible inflation averaging”. By committing to achieving inflation outcomes that average 2% over time, the Fed would make clear in advance that it would accommodate rather than offset modest upward pressures to inflation in what could be described as a process of opportunistic reflation.

On the second topic, expanding policy space, Brainard advocates a more mechanical approach for policy action when policy rates hit the ELB in future downturns. In particular, she sees advantages to an approach that caps interest rates on Treasury securities at the short-to-medium range of the maturity spectrum - yield curve caps (YCC) - in tandem with forward guidance that conditions lift off from the ELB on employment and inflation outcomes. Both would reinforce each other. In addition, once the targeted outcome is achieved, and the caps expire, any securities that were acquired under the program would roll off organically, unwinding the policy smoothly and predictably. Brainard expects that effective security purchases would eventually be smaller under such YCC system than compared with an outright buying programme.

Politics posing risks

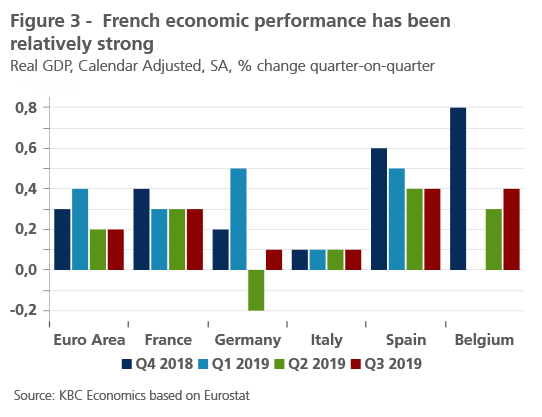

European political events in several countries are posing more risks to the outlook for the European economy. The French government’s plans to reform the pension system and replace different existing pension schemes with a single, universal system triggered a storm of social protest and a general strike. Though the protests are of political nature, there is a risk that the public outcry against the government's reform agenda may dent confidence and possibly economic growth. As was seen at the height of the yellow vest protests in 2018, consumer confidence and spending could significantly suffer from social unrest (see Box 2). Nevertheless, the recent performance of the French economy was strong compared to other euro area countries (figure 3). Clearly, recent economic and labour market reforms are having a positive effect on the economy. We remain confident that the French economic outlook is bright, conditional on no excessive social unrest.

Box 2 - France on strike against necessary pension reform

France is once more confronted with severe social unrest. Unlike the yellow vest protests that have continued for over a year, this time strikes are organised by the French unions. They are protesting against the pension reform that is currently being negotiated by the government of President Macron. This pension reform aims to replace the 42 existing pension schemes with a single, universal, points-based system, where one euro of contribution gives access to the same rights regardless of when it is paid or the status of the contributor.

The official goal of the reform is to improve the fairness and transparency of the pension system. Under current pension regimes, some workers such as train drivers can take their pension from the age of 52, which was originally seen as compensation for tough working conditions such as difficult hours and shift work. Another issue is that public sector pensions are calculated based on payments in the last six months before retirement while private sector pensions use the employee’s 25 highest-paid years of work.

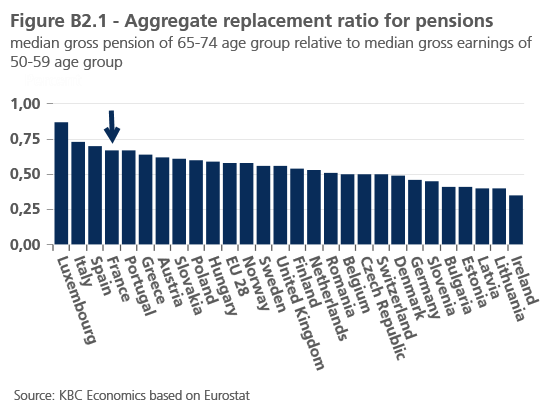

The proposed pension reforms make sense from an economic perspective. Apart from the perceived fairness, the affordability of the pension system is an important argument. The current replacement rate, the ratio of median gross pensions in the 65-74 age group compared to the median gross earnings of the 50-59 age group, is relatively high in France (figure B2.1).

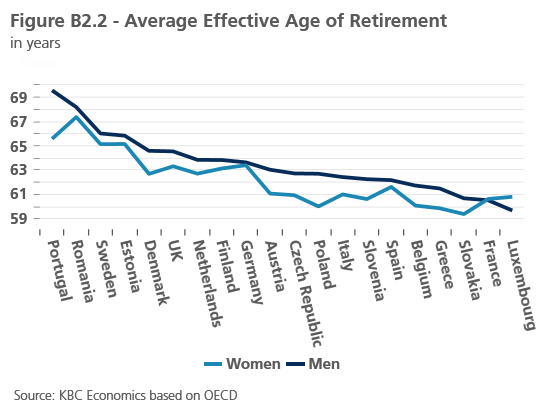

Combined with the relatively low effective retirement age of 60 years (figure B2.2), this results in a very expensive pension system, which will be strained even more as France moves towards an older population structure.

Pension reforms in France is a notoriously difficult thing to do. In 1995, the government of President Chirac was forced to back down from proposed changes to pensions of public sector workers after three weeks of strikes that immobilised much of the country’s infrastructure. The current strike is open-ended and could drag on for some time. Depending on the length and intensity of the strikes, the impact on French GDP growth in Q4 and on confidence levels could be significant. From a long term perspective, the next weeks will be crucial. If the government fails to implement the reform because of the protests, French public finances will be under heavy strain in the years to come. However, so far, the French government managed to achieve a substantial part of its intended policy reforms. So if France survives another period of social unrest, this pension reform may contribute to a better economic performance in a structural way.

The Spanish political impasse continues. The November election results kept the Spanish parliament highly fragmented. The formation of a government remains challenging, but the provisional deal closed between the socialist PSOE and Podemos looks promising. Nevertheless, even if a government is formed, political and policy uncertainty will remain elevated and the risk of repeated elections persists as this new government is unlikely to be very stable. Moreover, the impasse is likely to have fiscal implications as well. The budget for 2020 is still not passed and a roll-over of the 2019 budget is likely. In that case, there will be no (additional) fiscal stimulus measures. From a longer-term perspective, an unstable government is unlikely to find enough support for structural reforms. Hence, structural economic problems are unlikely to be tackled.

Another political source of uncertainty are recent events in Germany. The election of the new SPD leadership – one of the parties of the governing Grand Coalition – could cause some shift in the German policy stance. The outcome of the SPD election initially raised doubts about the continued existence of the Grand Coalition. However, a few days later the SPD stepped back from their earlier threat to pull out of the government alliance with the Christian Democrat Party. A collapse of the Grand Coalition before the federal elections of 2021 hence seems unlikely. The new SPD leadership continues to call for increased government investments and a reinforcement of the climate package. There is hence also a positive risk to economic growth attached to the new SPD leadership as they say the ‘Schwarze Null’ policy (also see KBC Economic Opinion of 07/05/2019 ) should not undermine continuing investment. Nevertheless, the most likely outcome is some limited additional stimulus in coming years, consistent with our scenario. The short-term impact on the business cycle will likely be muted given the traditional implementation lag of fiscal policy.

The outcome of the December 12th general election in the UK removes virtually all uncertainty about near term developments in relation to Brexit. The large majority won by the Conservative party of Boris Johnson ensures that he will be able to get parliamentary approval for the withdrawal agreement he negotiated with the EU in October. Hence, the UK will nominally leave the EU at the end of January 2020. However, to all intents and purposes the UK will continue to ‘enjoy’ the ties of membership during a transition period until the end of 2020. During this time Boris Johnson has promised a free trade agreement between the EU and UK will be concluded allowing a full and final departure at the end of 2020.

The unexpectedly large size of the majority won by Boris Johnson on December 12th means that he is no longer entirely reliant on small but previously important factions within the Conservative party or on the support of Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party. This should give him more flexibility in negotiations on a future trade deal with the EU and could translate into a ‘softer’ Brexit than would have otherwise been the case. It should also provide the UK with scope to extend the transition period beyond 2020 if required (one extension of that period can be allowed if it is agreed by mid-2020).

While near term uncertainty has all but disappeared, more fundamental issues around the precise form of any eventual deal and, more importantly, whether it is feasible to reach a comprehensive agreement by the end of next year will likely translate into bouts of uncertainty through much of 2020. Significantly, this suggests renewed concerns about the risk of the UK ‘crashing out’ of the EU could return at one or more points during the year ahead with immediate and likely material impacts on economic sentiment in the UK and its main trading partners.

Notwithstanding the decisive outcome to the UK election, the achievement of a full free trade agreement between the UK and EU by the end of next year looks exceptionally ambitious, especially since the UK government envisages a notably limited agreement focussed on goods trade to enable the UK greater scope to conclude trade deals with other countries. However, to the extent that the UK uses that scope, regulatory and other checks on trade with the EU will be increased (to prevent the integrity of the EU single market being compromised via the UK).

Apart from many European political risks, the US is moving into the impeachment procedure against President Trump. Though the Democratic Party has convincing arguments that the president abused his political power, it remains unlikely that actual impeachment will happen as the Republican Party holds the majority in the US Senate, which has the ultimate say on a conviction.

Elsewhere, there remain various political risks too. The street protests in Hong Kong continue after the major election victory of the Pro-Democracy camp. Though protests are still massively attended, no new violence occurred. Moreover throughout Latin America there is social unrest that will pose major challenges to local policy makers. However, we don’t expect any of these events to have implications on the global economic outlook.

Trade war at new fronts

The tone of the news flows about the US-China trade negotiations differs from day to day, but as of publication, expectations have grown that a phase-I trade deal will be signed by the deadline of 15 December. If there is an agreement, the US administration will not impose additional tariffs on imports coming from China. One of the main Chinese demands for a phase-I deal is that the US lowers some of the import tariffs that were already imposed. However, the US refuses to lower tariffs for a deal that doesn’t tackle core issues such as intellectual property protection. Another outstanding issue is how to ensure China purchases more US agricultural goods – which would likely be part of the deal as well. In any case, a phase-I trade deal would not mean the end of the trade issues between the economies as fundamental problems remain and the technology war is set to continue in the coming years.

Meanwhile President Trump is broadening the trade war to new fronts. Under the accusation that many countries have devalued their currencies over the past few years, President Trump announced import tariffs on steel and aluminium coming from Brazil and Argentina. President Trump also fanned the flames in the US-EU trade conflict. As a reaction to the French Digital Services Tax (DST), the US Trade representative announced additional duties of up to 100% on French products with an approximate trade value of $2.4 billion - roughly 5% of the value of total US goods imports from France in 2018. The DST was implemented in France earlier this year and is a 3% tax on gross revenues from large digital companies active in France. A US investigation into the tax determined that it discriminates against US digital companies (such as Google). This prompted the creation of a list of targeted products, including amongst other things cheese, sparkling wine, handbags and some beauty products, with the effects of the duties beginning in January after a public hearing. The European Commission already announced its intention to take the conflict to the World Trade Organisation.

The trade conflict casts a new threat to the outlook for the euro area. If it indeed comes to a direct confrontation between the US and the EU, the assumed recovery of the euro area economy might become endangered.

All historical quotes/prices, statistics and charts are up-to-date until 9 December 2019, unless stated otherwise. The views and forecasts provided are those of 9 December 2019.