Construction sector recovers but still faces major challenges

From 27 February to 7 March, the 62nd, this time virtual, edition of Batibouw will take place in Belgium. At first sight, the annual fair of the construction industry is starting under favourable skies. After a poor first half of the year, building activity was able to recover considerably in the second half of 2020, despite the second wave of the pandemic. Nevertheless, another difficult year may await the sector in 2021. Several indicators indeed indicate that the situation on the demand side remains uncertain. Moreover, there are signs of an impending oversupply in the residential construction market. The potential supply and demand problems come on top of other far-reaching challenges, including climate change and the Flemish ‘construction shift’, although these can also be a catalyst for new activity in the medium term.

Covid-19 hit construction activity unusually hard. This was especially true during the first wave of the pandemic. Surveys by the Economic Risk Management Group (ERMG) show that the loss of turnover in the sector up to May was higher than average in the economy. Figures from the National Accounts confirm this picture: in the second quarter, value added (in real terms and seasonally adjusted) in construction was 17.9% lower than in the last quarter of 2019, compared to 14.8% for the entire Belgian economy. Construction companies were not among the sectors where closures were mandatory. Nevertheless, almost half chose to cease operations at the height of the crisis, the main reason being the difficulty in complying with the rules. In construction, supply problems were generally quite acute. When the health crisis peaked in April, 45% of the construction companies surveyed by the ERMG at the time cited social distancing as the reason for the drop in sales, by far the highest figure of any sector. Staff shortages and supply chain problems were also seen as a bigger problem compared with most other sectors.

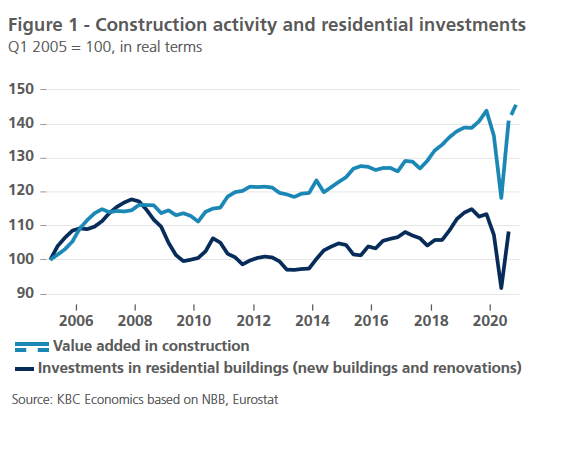

The dip in activity followed a prolonged period of strong growth in construction. In line with the positive development in the secondary housing market (i.e. sales of existing housing), household investment in residential buildings also increased strongly between 2014 and 2019 (Figure 1). During this period, its real growth averaged 2.7% per year. This is one percentage point higher than the average real GDP growth in Belgium in 2014-2019. 2019 in particular was an exceptional year: investments in residential buildings grew three times faster than the economy as a whole (5.2% vs. 1.7%). The main reason for the strong dynamics was undoubtedly the historically low interest rates. This made borrowing very cheap and also increased the interest of Belgians in investing in property to let. The abolition of the housing bonus in Flanders in early 2020 also boosted the market in 2019. Finally, the boom in the housing market in 2019 was also fuelled by the favourable situation in the labour market. Just before the outbreak of the Covid-19 crisis, the Belgian unemployment rate reached a low of 4.9%.

Recovery but with challenges

In the second half of 2020, the Belgian economy was already largely recovering. It was mainly industry, but also construction, that drove this recovery, while the service sector remained strongly affected. In the fourth quarter, real added value in the construction sector was again 1.2% above the pre-crisis level (Figure 1). For the whole economy it was still 4.8% below. The fact that the second wave of the pandemic had a much smaller impact on construction at the end of the year was probably due in part to the fact that companies had become accustomed to meeting the requirements to continue their activity safely. The resilient recovery of construction value added in the second half of the year was probably also partly due to the resumption of government investment in public infrastructure.

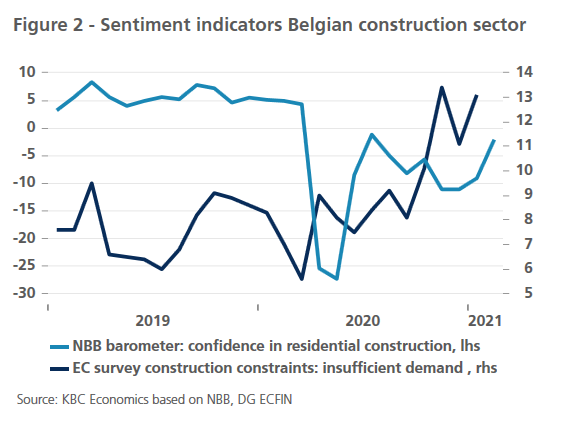

Nevertheless, the positive figures were surprising, especially in the fourth quarter (3.3% growth in added value quarter-on-quarter). Indeed, during the second wave of the pandemic, confidence in residential construction fell (Figure 2). Recently, it improved again but remained well below pre-crisis levels. The share of companies citing insufficient demand as the main reason for construction constraints also rose sharply at the end of 2020. The hesitant sentiment indicators suggest that uncertainty in the construction industry has not gone away. The still uncertain situation is also reflected in the latest ERMG survey. It shows that in February the construction industry still suffered a 7% loss in turnover as a result of the Covid crisis.

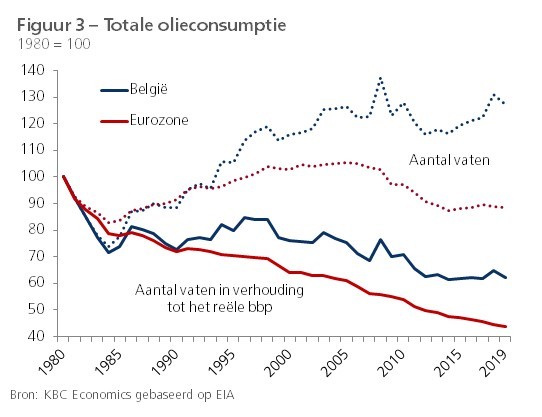

The additional job losses that are still to be expected could put a brake on household construction investment in 2021. On the other hand, interest rates are likely to remain around the current low level for quite some time, underpinning the affordability of (new) homes. On the supply side, there is the threat of a (local) oversupply on the housing market. It is somewhat alarming that the number of housing units has increased more strongly than the number of households over the past decade in virtually all of Belgium (Figure 3). Especially in the districts with large cities (in Flanders, especially Antwerp, Ghent, Hasselt, Leuven and Bruges), the ratio of housing units to households has increased the most since 2010. However, this trend must be put into perspective, as there were shortages of new housing in several places.

The potential supply and demand problems come on top of other far-reaching challenges that the construction industry will face in the coming years. These include the increasingly stringent sustainability requirements (which are pushing up construction costs), the policy plan of the Flemish government to cut back on open space for housing construction (the ‘construction shift’) and the application of new technologies (e.g. robotisation). However, such structural challenges are usually a catalyst for new activities and therefore offer medium-term potential for the construction industry.