China's tipping point

Introduction

The Chinese economy has reached a point where long-standing challenges have become near-term problems. Growth has been trending lower for over a decade while policymakers have struggled to shift the economy to more sustainable growth engines. This structural slowdown became apparent once again in 2021 as the volatile growth dynamics of 2020 faded. What’s more, the growth slowdown was compounded by several headwinds, most notably an energy crisis in September, a liquidity crisis in the real estate sector, and ongoing Covid-19 concerns combined with a zero-tolerance approach to the pandemic. As such, the Chinese economy started 2022 in a difficult position.

Notably, all of these headwinds reflect difficult policy questions facing Chinese officials ranging from the appropriate speed of the energy transition, the right approach to addressing risky leverage build-up in the economy, and the trade-off between covid restrictions and economic activity. But the policy challenges don’t end there. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, in particular, poses important geopolitical and economic considerations for China. All in all, the Chinese economy is in a relatively precarious position, and the policy choices made now will have significant repercussions for the years to come.

A decade-long slowdown

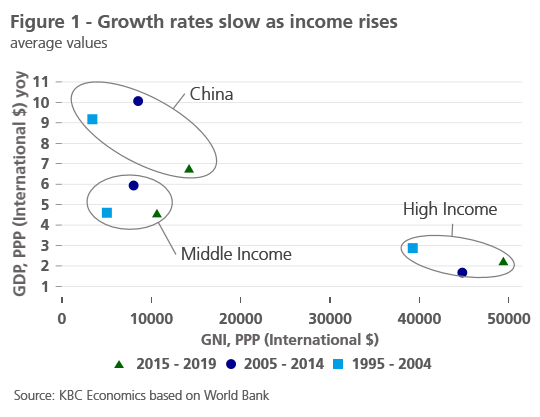

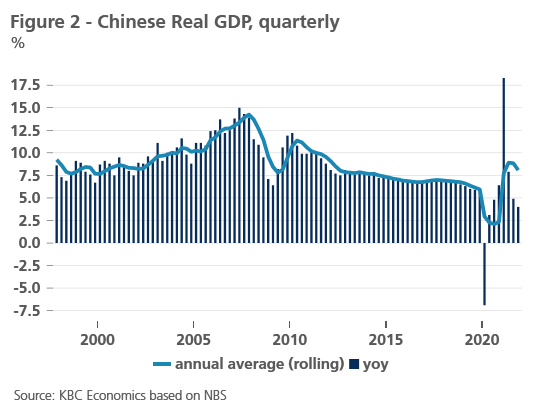

An economy in a perpetual slowdown for over a decade might sound like a dire situation, but when the starting point for GDP growth is in the double digits, such a trajectory is not so surprising. And indeed, as an economy’s income per capita improves, its growth rate tends to slow (figure 1). This is the case for China, which saw its real annual average GDP growth rate nearly double between 1999 and 2007 to above 14%. Aside from the recoveries directly following the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic, Chinese GDP growth has been in a downward slide ever since (figure 2). In some respects, such a slowdown is consistent with China’s improving income levels, however, China still has a long way to go to converge with high income countries. What’s more, as China grew to become the world’s second largest economy, slower Chinese growth now has important repercussions for global growth.

With year-over-year growth slowing to only 4.0% in the fourth quarter of last year, it starts to become clear why the government’s official growth target (announced in early-March) of 5.5% will be difficult, but not impossible, to achieve. A rebound in growth is necessary to achieve that target, but where that rebound will come from is not evident, with a number of headwinds present at the start of the year. Even the relatively strong average GDP growth of 8.1% recorded in 2021 reflected the low comparison in 2020 and masks the fact that year-over-year growth rates throughout the year slipped well below pre-pandemic levels (see again figure 2). And while there are both short-term and longer-term factors at play, the overlap between the two is becoming more and more apparent.

Short-term headwinds: real estate and covid

In the short-term, the clear threat to Chinese GDP growth is the ongoing Covid-19 crisis, with daily new cases in March 2022 spiking to levels not seen since February 2020. While certain provinces are currently seeing a sharper rise than others, the spike in cases is affecting multiple provinces and major cities, including Shanghai and Shenzhen. Although infection numbers are still low compared to what has been seen elsewhere in the world, the risk to economic activity comes from China’s strict “zero-covid” approach to dealing with covid outbreaks. Measures taken so far have included factory and business closures, road closures, and strict lockdowns of buildings or entire neighborhoods. For now, ports generally remain open, though with burdensome measures reportedly imposed on workers such as living on site. The rise in covid cases will therefore likely have an impact on both industrial production and consumption in Q1, and likely Q2, 2022.

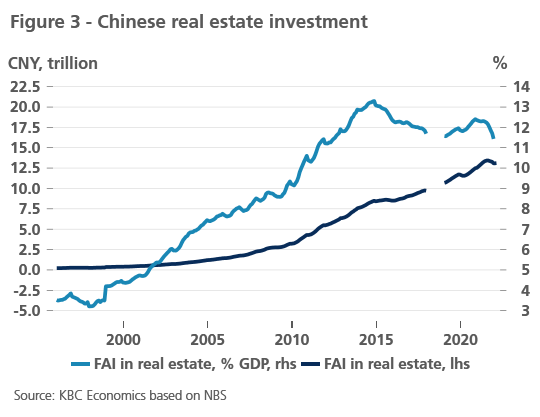

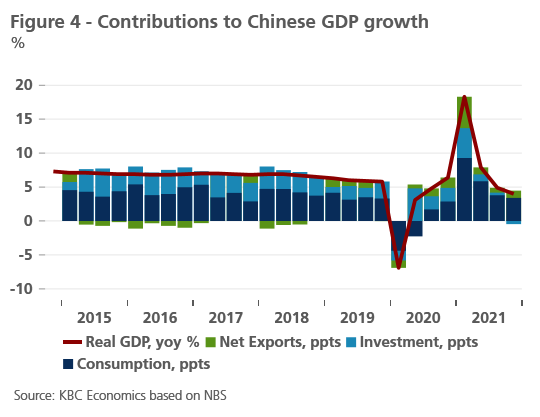

The other immediate headwind to growth in 2022 is the ongoing fallout from developments in the real estate sector. These developments refer to the regulatory crackdown on over-leveraged property developers, most notably through the “Three Red Lines” policy which placed limits on a property developer’s borrowing capacity based on its outstanding debt relative to assets, equity, and cash. This has led to a liquidity crisis in the sector and the partial debt default of a number of large developers (such as Evergrande, Shimao, and Kaisa). The liquidity pressures have had a ripple effect through the real estate sector, e.g. through asset fire sales, leading to a decline in property prices (down 1.8% since July 2021 in the secondary market) and a sharp drop in real estate investment from the middle of 2021. Because the real estate sector in China has an outsized impact on GDP (real estate investment as a percent of GDP amounted to 12% in 2020), this decline was a clear contributor to the weaker growth figures in the second half of 2021, with total investment providing a negative contribution to year-over-year growth in Q4 (figures 3 and 4).

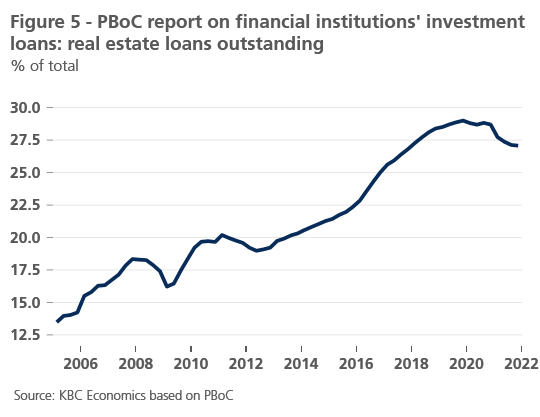

While the economic drag from the real estate sector liquidity crunch is already evident, there are other tail risks that could materialize as well. In particular, there could be spillovers to the financial sector from increasing non-performing loans (particularly from property developers but also potentially from households). According to data from the PBoC, financial institution’s outstanding investments in real estate loans stood at 27% of all investments as of Q4 2021, down from a peak of 29% at the end of 2019 (figure 5). Local governments' reliance on land sales for revenues could also put a squeeze on the fiscal capacity of local governments.

Long-term headwinds: debt and demographics

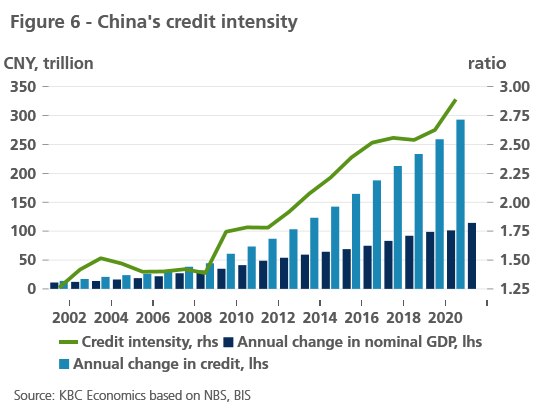

Next to the near-term factors listed above, there are also longer-term (and somewhat related) factors that will weigh on Chinese GDP growth going forward. The first of these structural problems is China’s very high debt burden across all sectors of the economy. Since the GFC, China has relied on debt-fueled investment as its main engine of growth. As a result, the government debt-to-GDP and corporate sector debt-to-GDP ratios have surged from 27% and 94% respectively in 2008, to 68% and 156% respectively as of Q3 2021. While this debt-spree supported the post-2008 recovery, over time, the efficiency of China’s credit-driven growth has waned, meaning more additional debt is needed to achieve the same boost to growth (figure 6). Knowing that this growth model is not sustainable in the long-run and can lead to financial stability risks, the Chinese government has gone through periods of focused de-leveraging of the corporate sector, though such efforts have often been at least partially put on hold in response to new headwinds to Chinese growth (e.g. the 2018-2019 trade wars and the 2020 covid crisis). Current events in the Chinese real estate sector are a clear example of how this long-run issue has become a pressing short-term concern.

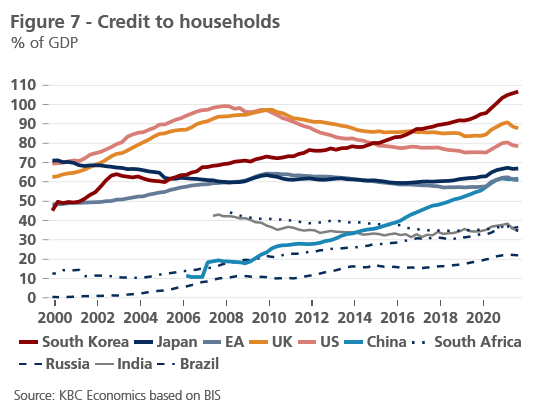

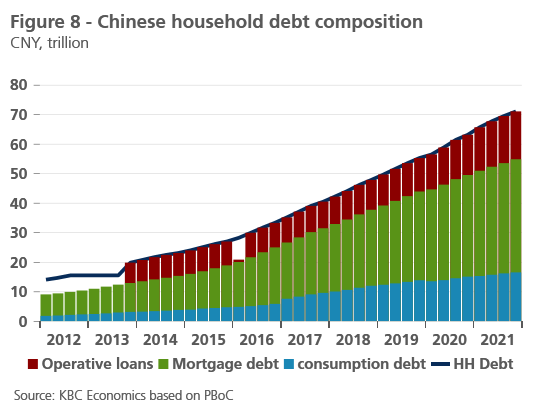

On top of the corporate sector and government debt build-up, there is also the issue of high household debt in China. As noted in a previous research report (China's household debt problem), household debt-to-GDP in China has far surpassed that of other middle-income economies, and is more on par with that of high-income economies like the EU or Japan (figure 7). This high debt load is an important factor weighing on switching China’s engine of growth away from debt-fuelled investment toward consumption. The fact that most of the debt accumulation has been driven by mortgages (figure 8), and that much of Chinese household wealth is tied up in the real estate sector, highlights that spillovers from the real estate sector can go well beyond weaker construction investment.

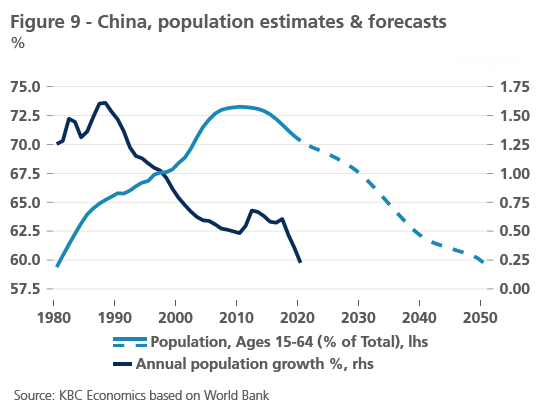

The second of these long-term structural problems for Chinese growth is China’s aging population. The percentage of the population aged 15-64 has been slowly decreasing since 2014, from nearly 73% to an estimated 70% in 2021. With annual population growth decelerating sharply as well, the decline in the working-age population is expected to continue for at least the next thirty years (figure 9).

This declining working-age population has several implications for the Chinese economy. First, it incentivizes higher household savings and can contribute to higher inequality, both of which are current challenges to increasing consumption growth in China.1,2 Second, a declining working age population means, all else equal, an economy must increase productivity in order to continue growing. Of course, if China wants to continue making progress toward becoming a high-income economy, its economic growth should come from higher productivity in any case so that GDP per capita, and not just GDP, continues to improve.

Policy objectives to balance

When China’s growth outlook is viewed from this lens, the government’s long-term policy priorities, e.g., as outlined in the fourteenth five-year plan adopted in March 2021, make more sense. A major focus of that plan is increasing incomes while reducing inequality, which would help boost consumption as a driver of growth. An emphasis on promoting Chinese innovation and external competitiveness would improve productivity growth and help compensate for demographic weakness. Addressing financial stability risks stemming from non-performing assets and the shadow banking industry means paring back China’s overreliance on leverage.

While these goals are important for China’s long-term economic health, achieving them is not so straightforward, with the knock-on effects of the crackdown on property developers being a case-in-point situation. As trouble in the sector has grown, Chinese policymakers are reportedly relaxing elements of the “Three Red Lines” policy, and the PBoC has rolled out monetary stimulus to support lending. Another illustrative example is China’s energy transition goal of reaching peak carbon emissions by 2030 and net zero by 2060. The introduction of “dual-control targets” to limit total energy consumption and the energy intensity of output led to an energy shortage in September 2021, and flexibility in enforcing the dual-control targets had to be introduced.

This policy tightrope that the Chinese authorities are walking is also relevant for current geopolitical events and China’s roll on the international stage. It is no secret that China and the US are locked in a geopolitical power struggle with technology and trade conflicts at its center. This geopolitical wrangling explains, in part, China’s non-condemnation of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Whether that non-condemnation will turn into full-out support remains to be seen, but such would be a significant policy decision with enormous (like costly) consequences for the Chinese economy. The freeze out of Russia from much of the US dollar-dominated global financial system, for example, could potentially bolster the international role of the Chinese renminbi as a work-around to some of the sanctions, but overall, China stands to lose from a significant decoupling of its economy from the coalition of pro-Ukraine countries.3

Conclusion

Chinese policymakers are faced with a number of important policy challenges, the resolution of which will determine China’s economic trajectory in the years to come. There is a very real possibility that the structural problems dragging down Chinese growth will continue, with real GDP growth trending below 3% in the medium term, as the debt-led and real estate-heavy growth model unwinds with no alternative to replace it. This would leave China stuck in the so called “middle income trap” of development stagnation. Or, Chinese policymakers may very well navigate the current challenges, providing just enough stimulus to support growth and innovation without adding to the country’s debt problem. China would continue its convergence with high income economies through industrial upgrading and an internal rebalancing away from savings toward consumption. Betting against Chinese policymakers’ ability to weather a storm has not proved to be a wise move in the past, but when a scale is at its tipping point, even minor developments can make the difference.

1. Zhang et. al. IMF Working Paper, 2018. "China's High Savings: Drivers, Prospects, and Policies"

2. Deaton, A, and C Paxson. 1997. “The Effects of Economic and Population Growth on National Saving and Inequality.” Demography 34 (1): 97-114.

3. Six reasons why backstopping Russia is an increasingly unattractive option for China | Bruegel