The ECB’s interest rate policy in times of QT

After more than a decade of Quantitative Easing in various forms, the ECB has started normalising its balance sheet. This reversal is being implemented by not reinvesting securities from its APP portfolio that reach their maturities, on top of repayments of TLTROs. This way, excess liquidity is gradually being withdrawn from the market. Among other consequences, the ECB is now reviewing what the implications of these falling excess reserves are for the implementation of its interest rate policy. A return to the corridor system, which was in place until the Great Financial Crisis, is in principle feasible but probably faces too many uncertainties. The more likely framework is a continuation of the current floor system. Within that system, the ECB would need to choose between two alternatives: either the demand-driven version (as currently used by the Bank of England), or the supply-driven version (as currently used by the Fed and ECB). Both versions would have advantages and disadvantages for the euro area. Whatever the ECB’s final choice will be (probably the supply-driven version), it will be a delicate balancing act. Accurately assessing the market’s actual underlying liquidity preferences is extremely difficult, especially after more than a decade of central bank domination of the euro area money market.

Since March 2023, the normalisation (Quantitative Tightening)off the ECB’s balance sheet has started. What does this imply for the ECB’s interest rate policy framework after broadly a decade of expansion in excess reserves, first by LTROs, then TLTROs, SMP, APP and, last but not least, the PEPP when the pandemic started?

The repayment of TLTROs by euro area banks and the gradual run-down of the Eurosystem’s monetary policy bond portfolio imply that the Eurostem’s balance sheet is likely to decline significantly over the coming years. According to ECB Board member Schnabel, the Eurosystem’s targeted balance sheet size should be “[...] only as large as necessary to ensure sufficient liquidity provision and effectively steer short-term interest rates towards levels that are consistent with price stability over the medium term.”

The ECB estimates that, under plausible assumptions, the path of reduction of excess liquidity would lead to a full absorption of excess liquidity only by 2029. In this scenario, the Eurosystem’s balance sheet would still be about three times the size it was in 2007. If this time horizon is correct, and if excess reserves would still be desired for monetary policy purposes, the balance sheet would have to start growing again after 2029.

Corridor versus floor system

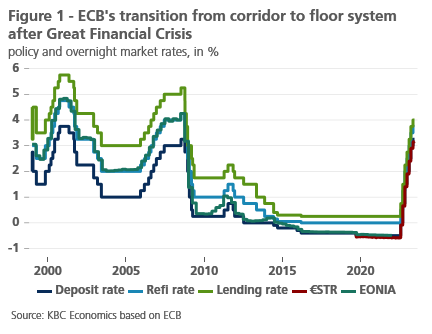

At least for the coming years, excess reserves will inevitably remain a crucial feature of the monetary system. The ECB is currently reviewing its operational framework for interest rate policy in this context and expects to conclude it by the end of 2023 (for an overview see Schnabel (ECB), March 2023). In our view, the result will most likely be that the current ‘floor system’ will be maintained (Figure 1).

In that system, the deposit facility rate (DFR) is the relevant policy rate steering the short-term money market rates. This is different from the pre-QE ‘corridor system’, where the main refinancing operations (MRO) rate acted as effective policy rate. While in this ‘corridor’ system, the ECB does not fully meet the market’s aggregate liquidity demand. The (somewhat punitive) DFR and the marginal lending rate (MLR) are charged for occasional individual surpluses or shortages of reserves. As a consequence, market rates will fluctuate around the MRO rate, and be bounded by the MLR and the DFR (as was the case between 1999 and 2007).

A maintained floor system would probably not only be based on the continued presence of excess liquidity, but also, on an indefinite extension of the ‘full allotment’ policy for banks in MROs. With this policy, the ECB explicitly abandoned its ambition to control the liquidity supply, providing whatever liquidity required to banks with sufficient collateral.

The main argument in favour of a floor-system is the large uncertainty about the precise liquidity demand by the banking sector. In order to reduce market volatility, it seems therefore appropriate to fix market interest rates around DFR and let the monetary base adjust freely. Abruptly withdrawing excess reserves to the point of engineering a small shortage, as would be required in a corridor system, would generate financial stability risks as to whether markets would function properly again if the ECB were to withdraw from its current dominant market position.

Two ‘floor’ options: supply-driven...

A floor system can be implemented in (at least) two ways. The Fed and the ECB currently use a ‘supply-driven’ system, and effectively create and maintain excess reserves as a result of a substantial monetary policy (bond) portfolio. The main advantage of this system is that it is operationally simple, since there is no need for the central bank to accurately estimate the liquidity demand of the financial sector. Hence, this system ensures that the interest rate signal is not diluted even if the amount of liquidity is volatile.

The downside, however, is that, with increasing level of reserves, the control over market interest rate is not perfect. For example in the euro area, it has led to an increasingly ‘leaky floor’, i.e. market rates (€STR) dropped below the deposit rate as an increasing amount of liquidity is held by non-banks without direct access to the ECB deposit rate facility. Moreover, in this system, QT may lead to concentrated reserve scarcity in parts of the financial system because of the unequal distribution of reserves among euro area banks. This may lead to upward pressure on market rates even when the aggregate amount of excess reserves is still high. Finally, this system may worsen bond market liquidity conditions for benchmark bonds in relatively smaller financial markets, such as in the euro area compared to the US, and hence create a scarcity premium (for German Bunds in this case).

... or demand-driven

An alternative floor system is demand-driven, as used by the Bank of England. In this system the central bank can afford to hold a smaller monetary policy portfolio than in the supply-driven option, but in addition it organises very frequent repo operations to supply banks with whatever additional liquidity they request. This system is also conceptually simple, robust, and vulnerable to ‘leaking floors’ in times of expanding excess reserves. A specific disadvantage is the potential stigma a bank may face if it uses these central bank lending facilities frequently. The UK supervisor tried to mitigate this stigma problem by clearly stating that these activities would be viewed as normal participation in money market operations. The demand-driven system may, by construction, also provide better insurance against market fragmentation, since liquidity distribution is likely to be more even, and in any case more consistent with individual banks’ liquidity needs. Last but not least, this system allows central banks to safely learn again about the market’s underlying liquidity preferences. This process may, however, take some time to lead to robust and accurate estimates. In the meantime, a predominantly supply-driven floor system appears to be the most likely outcome of the ECB’s policy framework review.