Russia: rebuilding buffers is not enough to kick-start growth

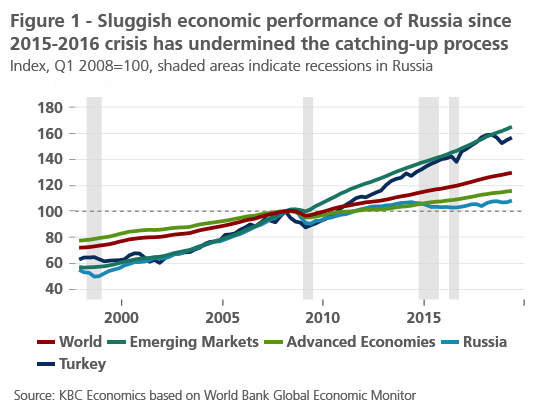

The Russian economy has continued to recover from the 2015-2016 economic crisis that was triggered by a dual shock of tumbling oil prices and international sanctions. A prudent post-crisis macroeconomic mix, i.e. tight fiscal and monetary policy, has helped to rebuild buffers and increase resilience to external shocks. Despite the surprising acceleration of growth last year, the underlying economic momentum remains weak as the economy is plagued by structural weaknesses. The economic model continues to be excessively reliant on hydrocarbon production and features a toxic cocktail of state capitalism including a substantial state footprint and weak institutional quality. This, combined with the adverse impact of international sanctions, contributes to anaemic potential growth that undermines the catching-up process to developed economies.

The Russian economy continues on its recovery path following the economic crisis of 2015-2016, which was triggered by a dual shock of tumbling oil prices and international sanctions related to the annexation of Crimea. Nevertheless, despite the acceleration of annual growth to 2.3% last year, the underlying economic momentum remains weak (0.7% year-on-year in the first half of 2019). The pick-up in economic activity was largely due to a one-off factor, i.e. the completion of energy construction projects in the Tyumen region, thus falling short of a strong and broad-based recovery trend. Indeed, the post-crisis recovery since 2016 has been sluggish, with average real GDP growth at only 1.4% compared to 3.0% following the global financial crisis (2010-2014), and an even more robust average annual expansion rate of 6.9% after the Ruble crisis (1999-2007).

While buffers were rebuilt…

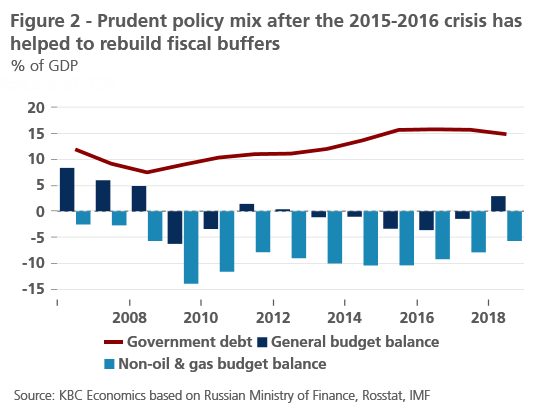

The poor post-crisis performance reflects the government’s deliberate decision to rebalance the policy mix in order to rebuild buffers and increase resilience to external shocks. This involved tight monetary policy, which has only recently been gradually eased towards a more neutral stance. Still, real interest rates remain among the highest in emerging markets at around 2.5%. Such a focus on macroeconomic stability also encompassed a restrictive fiscal policy (underpinned by an increase in VAT rates and a parametric pension reform) resulting in a budget surplus of 2.8% of GDP last year, the highest since 2008. The private sector followed the course with a sharp deleveraging, primarily focused on redeeming foreign debt. Gross external debt is now entirely covered by ample foreign reserves of $530 billion, underpinning the overall strong external position. As a result, the Russian economy stands out as one of the least vulnerable in emerging markets, having substantially increased its absorption capacity in case of an adverse external shock.

…structural weaknesses persist

Nonetheless, the economy continues to be plagued with persistent structural weaknesses, limiting potential growth which is currently estimated to be just around 1.5%, well below the emerging market peers. The Russian economic model is excessively reliant on hydrocarbon production, which is responsible for more than 60% of exports and 40% of federal budget revenues. Hence, while the higher oil prices helped the recovery after 2016, their limited upside potential is set to provide only a mild boost to growth in the medium-term. What is probably even more worrying is the toxic cocktail of state capitalism; the government footprint remains high with the state accounting for more than a third of gross domestic product and almost half of total employment, which undermines the competitive environment. In combination with weak institutional quality, an unfavourable demographic trend and international sanctions (hampering technology transfers from abroad), this weighs on private investment and ultimately work as a drag on productivity.

Despite ambitious government goals, no major steps have been taken yet to tackle these constraints. The implementation of national investment projects that total $390 billion, or around 3% of GDP per year for the period 2019-2024, has seen a very slow start, and while we expect that the ramp-up in government spending will stimulate growth in the short term, their long-term impact (even if implemented fully) is questionable. Meanwhile, private consumption is likely to remain weak, undermined by stagnating real disposable income which is still below its 2014 level. Moreover, we see a further downside risk stemming from recent regulatory measures taken by the Central Bank of Russia to curb buoyant double-digit credit growth, which partly compensated for lower real disposable income. Investments continue to be hampered by a poor business climate and persistent uncertainty, in particular from the deteriorating geopolitical situation as the US sanctions have been gradually tightened and their possible further extension remains imminent, with additional sanction legislation being evaluated by the US Congress.

Overall, we expect a mild pick-up in growth from an estimated 1.2% this year to 1.7% in 2020 on the back of looser fiscal and monetary policy. However, this will bring the growth rate merely to potential, which is set to remain chronically low, undermined by the abovementioned mix of deeply rooted structural constraints. Hence, despite the fact that Russia has rebuilt its buffers and is well prepared to shoulder external shocks, a robust kick-start of growth is unlikely, which rapidly diminishes the chances of a fast catching-up to developed economies.