Diversity of forms of cohabiting underestimated in policy

Households have changed drastically in recent decades. The classic ‘married family’ with a mother, father and two children has not been the norm for some time and has made room for several non-traditional forms of habitation. Belgium is one of the countries within Europe where the changes are happening the fastest. The government still has done little to respond to this. In its policies, it should increasingly take the consequences of the growing diversity into account when it comes to forms of habitation and eliminate discrimination as much as possible. Companies also focus far too much on the traditional family and will have to deliver more and more customisation to accommodate the increasingly diverse types of household.

Every second Sunday in February, the institution of marriage is celebrated in the form of World Marriage Day. There are not many reasons to celebrate, however. The life-long commitment of marriage is, after all, a prospect that appeals to fewer and fewer people. Since the 1970s, weddings – and church weddings in particular – have seen significant declines as has the corresponding classic family in Belgium. In their place came a patchwork of many non-traditional families and forms of cohabitation: unmarried (official or unofficial) cohabiting, newly formed families, single parents, LAT (living apart together), weekend relationships, rainbow families, multi-generational families, and so on.

This went hand in hand with a growing complexity and instability of the households. In concrete terms, this was expressed in a sharp drop in the average size of families and more and more children who do not live with both parents. Within Europe, Belgium is one of the countries where the changes in forms of cohabitation are taking place the fastest. A quarter of children in Belgium do not live with both (married or cohabiting) parents. That figure is only higher in Denmark and Latvia. Together with the UK and Ireland, Belgium is also counted among the EU countries with a large share (over 6%) of single parents with one child or more.

The fastest-growing type of household is singles without children (living in). In Belgium, the ‘singles’ group already represents more than a third of all households and nearly a fifth of all adults. These numbers are again far above the European norm. It partly concerns persons who are transitioning from one relationship to another, but more often it concerns a long-lasting or permanent living situation. As a result of the ageing population, there is an ever-increasing group of singles aged 65 and up, usually seniors who have lost their partner. Even more remarkable is that people in the younger age groups are more often, albeit not consciously, living alone. In Belgium, two out of three singles are younger than 65, compared to just slightly more than half in the whole of the EU.

Most demographers are predicting that the trends observed concerning new forms of (co)habiting will further expand over the coming decades. More specifically, they are assuming that the ‘thinning’ of households will continue to rise. This is particularly expressed in the fact that partners (and their children) will be even more loosely connected, as well as a further increase in the number of singles. That development shall integrate with other social economic trends, such as the ageing of the population, the increasing international migration and mobility of citizens, urbanisation and new forms of housing. Innovations in ICT, social networking and medical applications are likely to contribute to making the way in which people cohabit even more dynamic, too.

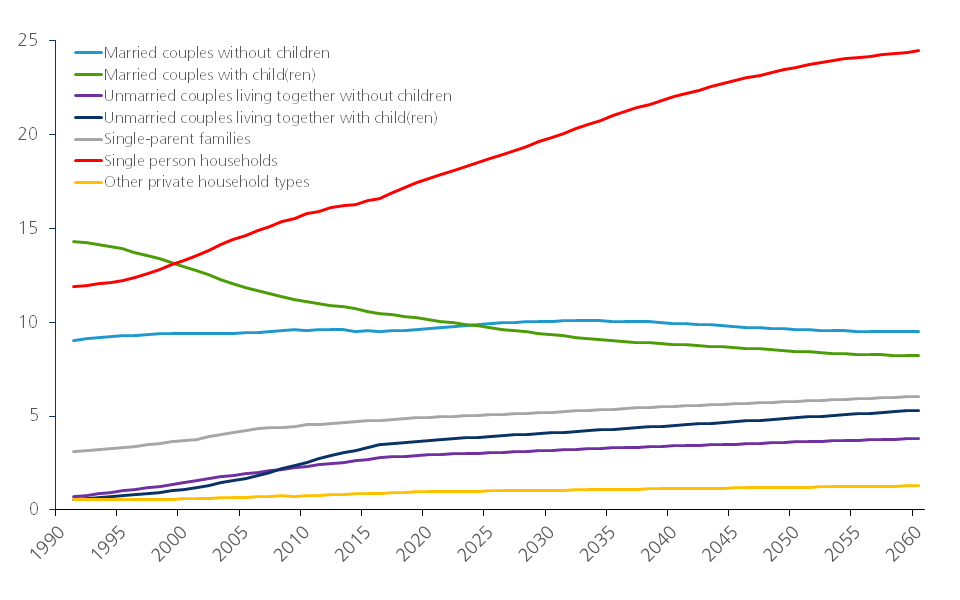

In Belgium, the Federal Planning Bureau issues predictions as part of its annual population forecasts about what the households will look like in the coming decades (see figure). Most striking is the strong further increase, both absolute and relative, of the singles (one-person households). In 2060, the end of the forecast horizon, their share amounts to 42% of all households, compared to 34% today. The share of cohabiting couples and single-parent families also continues to increase at the expense of married couples. There is no further division among the group of cohabiting couples, but it can be expected the rise thereof will also be accompanied by more newly formed couples and families.

Figure 1 - Evolution of various household types in Belgium 1990-2060 (amount in 100.000)

Source: KBC Economic Research based on data from the Federal Planning Agency

Major consequences and challenges

This rapidly and strongly changing situation concerning forms of cohabitation creates important societal and economic changes. As such, the demise of the traditional family and the substantial increase in the number of singles go hand in hand with a higher risk of poverty and social exclusion. After all, weaker ties undermine the joint care of, and for, family members. According to Eurostat figures, singles in Belgium represent roughly one third of all households but still also comprise half of all the poor. Furthermore, there is also a significant impact on the environment. On average, smaller and more unstable households result in significantly more energy and water consumption, waste production, traffic flows and housing units per head. As far as housing is concerned, there is the threat of a growing mismatch between the available housing stock and the housing needs of the households. The thinning of families, and the growing number of singles in particular, requires more small dwellings. New forms of cohabitation will increasingly necessitate more flexible forms of (co)habitation, such as co-housing. Given that decisions on buying a car, food, etc. often take place at a household level, last but not least the changes concerning (co)habiting also have an important impact on future consumption patterns. The even more diverse composition of the households will result in a fragmentation of needs, requiring more customised products and services for the various household types.

The stated changes result in considerable challenges, both for the government and companies. Although the classic family is no longer the norm, it still is for the majority of government policies. In said policies, the government should increasingly take the consequences of the growing diversity into account when it comes to forms of habitation and provide more neutral forms of habitation legislation and regulations. Discrimination between forms of habitation still exists today in the form of a higher tax burden on singles, for example. Companies also still often use traditional models of consumer segmentation that pay little attention to new, more complex and dynamic forms of (co)habiting. The changes will force them to offer more and more customised products and services to meet the specific needs and preferences of rapidly changing household types. This applies to the sharply rising group of singles in particular.