US labour force dropouts and COVID considerations

Click here to open the PDF

The impressive recovery in the US labour market since the onset of the pandemic can be seen from two different perspectives. From one perspective, the unemployment rate, at 4.6%, is not far from the low of 3.5% reached in January 2020, and quit rates are at highs not seen in the past two decades, suggesting the labour market has nearly fully recovered and is rather tight. From another perspective, total employment is still 4.7 million jobs less than pre-pandemic and there are still 3.1 million less people in the labour force. Understanding what is behind the still lagging labour force participation is key to understanding whether the US labour market really is tight, and consequently, implications for inflation. While recent higher inflation is mainly attributed to transitory price pressures, like the rebound in energy prices and supply chain bottlenecks, tighter labour markets can feed inflation further, mainly through wage pressures but also through labour shortages potentially adding to supply-side disruptions. Secondary effects of the COVID crisis could be an important driver of the drop in labour force participation. In particular, an increase in hours spent on unpaid childcare work and the possibility that COVID infections themselves are causing lingering symptoms that contribute to an incapacity to work may be important drivers to consider. While the former can be addressed by policy action, the latter would suggest the labour market is already on the tight side.

Signs of a tight labour market…

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 devastated the US labour market. The unemployment rate shot up from 3.5% to 14.8% between February and April of that year, accounting for a loss of over 25 million jobs (Figure 1). Unsurprisingly, nearly four-fifths of the jobs lost in April 2020 were in the services sectors, particularly in leisure and hospitality (36% of total lost jobs), education and health services (12.7%), retail trade (10.9%), and professional and business services (10.8%) (Figure 2).

To the surprise of many (and unlike previous economic recoveries), the bounce-back in the employment rate was sharp and swift, and by October 2020, the unemployment rate had already fallen back to 6.9%. The recovery in the year since has been somewhat slower, but the US unemployment rate is back down to 4.6% as of October 2021.

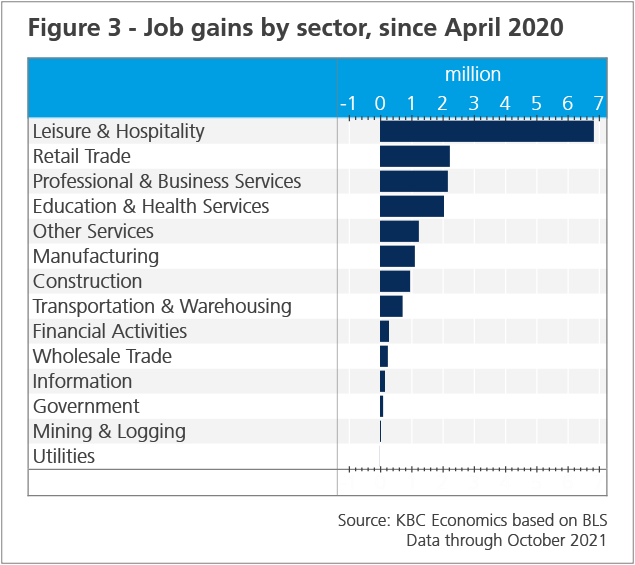

By sector, the recovery through October 2021 has mostly mirrored the losses seen in April of 2020, with 38% of job gains coming from leisure and hospitality, and between 11-12.5% each coming from education and health services, professional and business services, and retail trade (Figure 3).

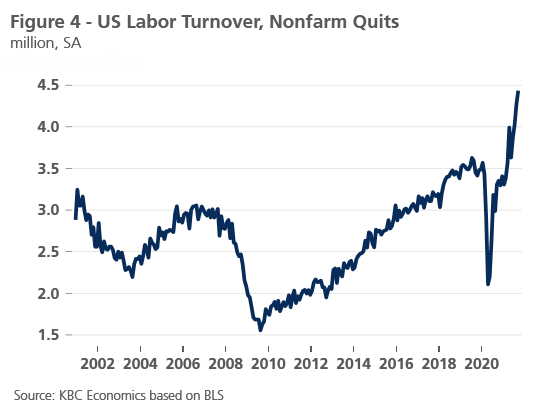

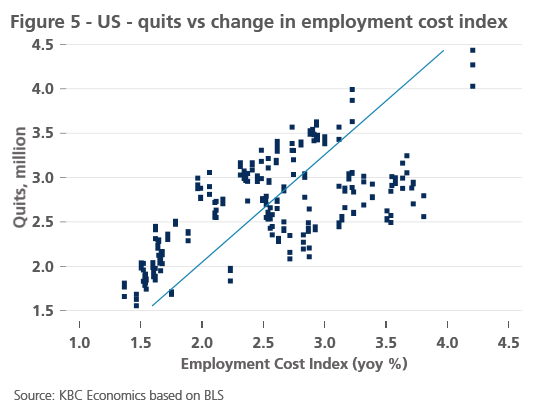

In another sign of the strength of the labour market, the number of people quitting jobs each month reached 4.4 million in September 2021, a high not seen in the past 20 years (Figure 4). A high quit rate is a not only a sign of a tight labour market, with employees confident they can find a new job elsewhere. It can also be associated with higher wage pressures, as those moving jobs tend to seek an increase in pay when they move (Figure 5).

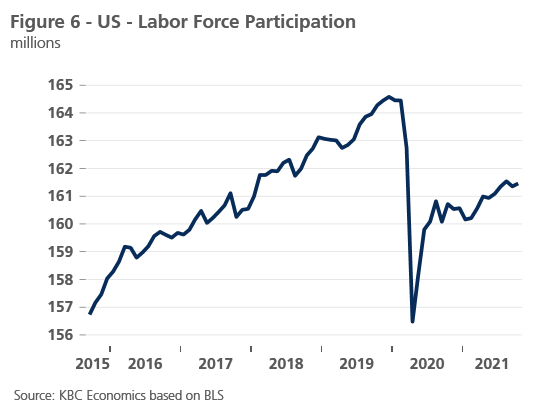

Labour force slack

But is the US labour market actually tight? Overall, the labour market has recouped over 20 million jobs in the 18 months since April 2020. That translates to a net loss of 4.7 million jobs compared to the pre-pandemic situation. This still substantial net loss, however, is not fully reflected in the unemployment rate figures. This is because there was a corresponding drop in labour force participation by roughly 8 million people at the onset of the pandemic. While labour force participation (16 years and over) has partially recovered since April 2020, as of October 2021, there are still 3.1 million less people in the labour market compared to the start of 2020 (Figure 6).

Counting those missing 3.1 million labour force participants as part of both the unemployed and the labour force would raise the unemployment rate to around 6.4%. Understanding what is driving this incomplete recovery in labour force participation, therefore, is key to understanding whether the US labour market really is tight, and consequently, how wage-driven inflation dynamics could evolve.

Unpaid childcare

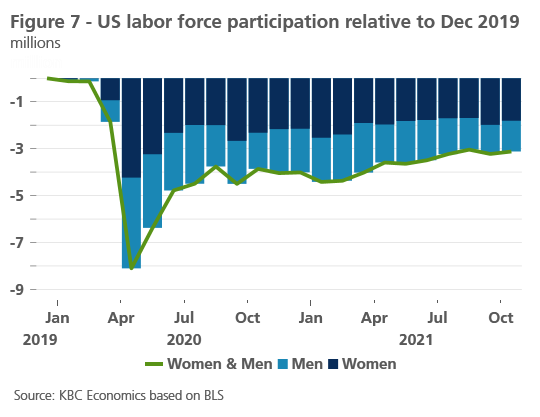

Given that the drop in labour force participation coincided with the onset of the pandemic, it is important to consider how ongoing pandemic dynamics are playing a role. For example, it is notable that from peak to trough, more women dropped out of the labour force compared to men, and the recovery in labour force participation for women has since been weaker (Figure 7).

While women’s participation in the labour market has come a long way over the past seventy years (increasing from 34% in 1950 to 57.7% in 2019) and the home model with men as the sole breadwinners has declined significantly, a study by the Center for Global Development1 found that, globally, the pandemic likely generated significantly more unpaid childcare work for women (173 hours) compared to men (59 hours) in 2020. This gap is skewed upward by the more disproportionate split of unpaid childcare between men and women in low- and middle-income countries. However, even in the US, the ratio of female to male time devoted to unpaid care work is still 1.61 according to the OECD.

Back in August 2020, the Bipartisan Policy Center2 surveyed parents of children under the age of 5, who had been employed as of January 2020. According to the survey, for 32% of parents who had been using formal childcare services, that provider was temporarily closed, and 44% of parents reported that they could not work without childcare. Furthermore, for those that were using a formal childcare provider before COVID, as of August 2020, 32% said a family member or relative was caring for their child, 13% said they were alternating work hours with someone in the household to provide care, and 8% said they were working less hours. It is also worth noting that those households that were previously relying on a relative such as a grandparent for childcare may have needed to find new arrangements given the risks associated with COVID by age.

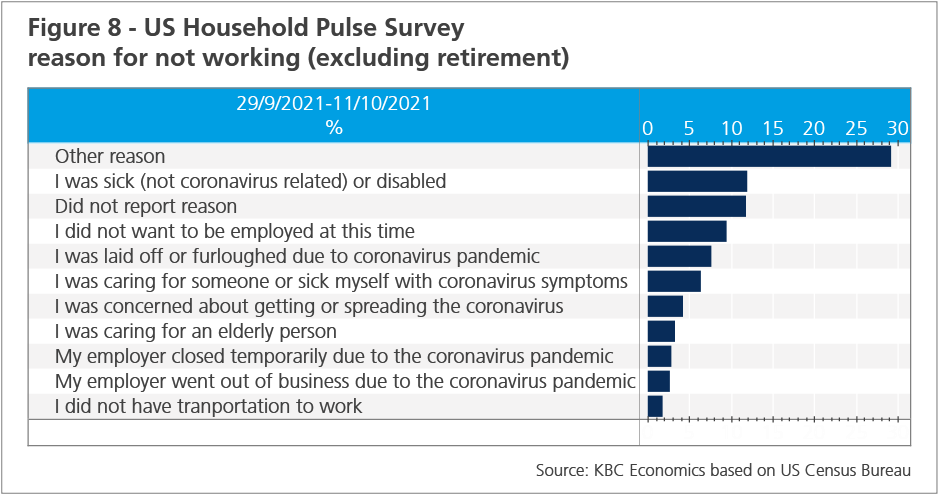

Regardless of to what extent the increased need for childcare arrangements during COVID have fallen disproportionately on women, the childcare situation is clearly an important factor driving the drop in the labour force. And although schools and childcare providers have generally reopened, they are still plagued by frequent closures and quarantine requirements, and some childcare providers have closed permanently, making options more expensive. In the US Census Bureau’s weekly Household Pulse Survey of September 29 - October 11, 2021, 8.5% of people not working at the time of the survey (excluding retirees) were not working because they were caring for a child not in school or day care. A further 6.4% were not working either because they were caring for someone with coronavirus symptoms or because they were sick themselves with coronavirus symptoms (Figure 8).

What about Covid itself?

The above figure raises the point that we also must consider the impact of COVID itself on the labour force. Afterall, over 45 million cases have been reported in the US and well over 700,000 people have died as a result. At first glance, the tragically high number of deaths may seem unrelated to labour force participation given that COVID fatality rates were much higher among older people who might no longer be in the labour force. However, those over 55 still make up a substantial portion (24%) of the US labour market. And of the 3.1 million missing from the labour market, 28% (or 869,000 people) are those over 55. Indeed, if we focus on just the age category of 55-64 (assuming an average retirement age between 62-65), over 104,000 people in that age category have died from COVID in the US. Of course, not all of these people were still in the labour market, but the number itself would account for 13.6% of the missing labour market participation for that age category.

While deaths alone are likely not a leading COVID-related factor behind the fall in labour participation, COVID infections are another avenue to consider, as even a non-severe COVID infection could keep someone temporarily out of work. Notably, the US is one out of only two OECD countries that doesn’t have statutory paid sick leave. A temporary benefit was introduced in the case of COVID, suggesting a COVID infection itself would not cause someone to drop out of the labour force completely, but so-called “Long COVID” could indeed play role.

Long COVID, or “Post COVID-19 condition” as defined by the World Health Organization includes symptoms of fatigue, shortness of breath, cognitive dysfunction, and others that “have an impact on everyday functioning,” lasting for at least 2 months. A recent study by Belgium’s Federal Knowledge Center for Health (KCE)3 found that at least one out of seven people infected still show such symptoms six months after infection, with a clear impact (60%) on people’s ability to return to work at full capacity or at all. What’s more, long COVID appears to be most prevalent among those aged 35-69, a significant cohort of the labour market.

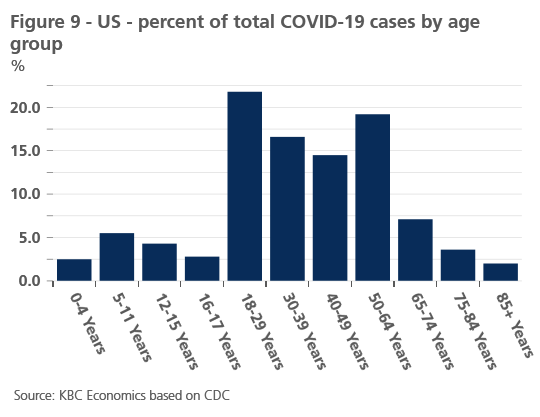

Estimates regarding the percent of people suffering from Long COVID vary given non-standardized definitions of the illness, but we can use KCE’s figure to get a general sense of the impact of long COVID on the US labour market. According to CDC data, 72% of cases in the US have occurred in those aged 18-64 (Figure 9). This amounts to just over 33 million people. If we assume that one out of seven of these people have some form of long COVID, that amounts to 4.6 million people. If 60% of those people find that long COVID is causing an incapacity to work, that would be 2.7 million people either out of the work force or with reduced working hours. While there is not enough data yet to say how long these symptoms of long COVID last, and whether or not those infected earlier in the pandemic are still finding themselves unable to work due to such symptoms, long COVID could, theoretically, account for a large share of the “missing” labour force.

Finally, it is worth noting that the pandemic appears to have driven a wave of early (or earlier than initially planned) retirements. The US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, which started in May 2020, supports this. In the first week the survey was held, the percentage of people that reported they were not working due to being retired was 31.5%. As of the latest survey (September 29-October 11), that figured had risen to 42.7%. While there may be various driving factors behind these early retirements (including potentially health considerations), this trend points to a more structural movement out of the labour force.

Implications

If the only-partial recovery in the US labour market is due to indirect factors stemming from the COVID crisis, this has important implications for understanding the health of the labour market. Shortages due to limited childcare options are semi-structural and can be addressed via policy options to improve childcare services. Notably, providing two years of free preschool, subsidising childcare for low-income families, and extending the child tax credit are part of Biden’s policy agenda currently under negotiation. Implementation of such policies could help pull more people into (or back into) the labour market.

A drop in labour market participation due to the effects of long COVID may be a different story, however, as we don’t yet have a clear understanding of just how long such effects will last. Hence, there could be some element of the drop in labour market participation that is more structural and won’t return. This would suggest that the labour market really is tight and—combined with a recent wave of labour strikes in the US—upward pressure on wages could follow suit.

1 https://www.cgdev.org/publication/global-childcare-workload-school-and-preschoolclosures-during-covid-19-pandemic

2 https://bipartisanpolicy.org/download/?file=/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/BPC-Child--Care-Survey-Analysis_8.21.2020-1.pdf

3 https://kce.fgov.be/en/long-covid-pathophysiology-%E2%80%93-epidemiology-and--patient-needs