The quest for the right euro area policy mix

Rising inflation and worsening growth prospects pose dilemmas for macroeconomic policy in the eurozone. In order to maintain its credibility as a guarantor of price stability, the ECB will have to tighten policy earlier and probably more sharply than previously assumed, even though this may make economic growth more difficult. This will also put an end to the central bank buying up almost all the increase in public debt and keeping interest rates on public debt low. Fiscal authorities will again become fully responsible for the sustainability of public finances. In principle, this is monitored by means of the European budget rules. But in view of the unprecedented rise in energy prices and the war, the European Commission is proposing to suspend their strict application until 2023. This should not lead to the continuation of the almost unlimited government support to the economy, which was justified during the Covid-19 crisis. After all, the energy price increase makes the economy as a whole less wealthy. This cannot be borne by the government alone. In order to avoid turbulence in bond markets, the budget margin should only be used for temporary, unforeseen expenses, while new structural expenses should be compensated by savings or new revenues. It would also be beneficial to create a European budgetary instrument to absorb economic shocks.

Sometimes it snows in April

The energy price shock and the invasion of Ukraine by Russia have placed European policymakers in a difficult balancing act in the search for an appropriate macroeconomic policy mix. The expectation was that the (hoped for) end of the pandemic would bring about an economic recovery allowing for a gradual normalisation of monetary policy and a return to fiscal orthodoxy. The European-debt-financed NextGenerationEU would promote economic recovery and boost the greening, digitisation and structural strengthening of European economies. But sometimes it snows in April, and expectations are dashed.

Worsening growth prospects and soaring inflation are causing policy dilemmas. The ECB is now ending its (net) purchases of (mostly) government debt. It will then have to raise its policy rate much earlier and probably more sharply than was generally assumed at the start of the year, at least if it does not want to put at risk its credibility as a guardian of price stability in the eurozone. Direct increases in consumer prices due to higher prices for energy and other commodities cannot be countered by monetary policy. However, in the interest of price stability over the medium term, the central bank must avoid second-round effects and any slippage in inflation expectations in the event of such supply shocks, even if this implies that it will further complicate or stifle economic growth.

With its tighter policy, the ECB will, above all, also create a much more difficult monetary environment for fiscal policy. Over the past two years, the combination of a very accommodative monetary policy and a strong fiscal expansion has allowed the eurozone economy to get through the pandemic all in all without major damage. The nearly 15% drop in real GDP at the outbreak of the pandemic in the first half of 2020 was already completely reversed by the second half of 2021. And at 6.8% of the labour force, the unemployment rate in April 2022 was at its lowest level since the introduction of the euro.

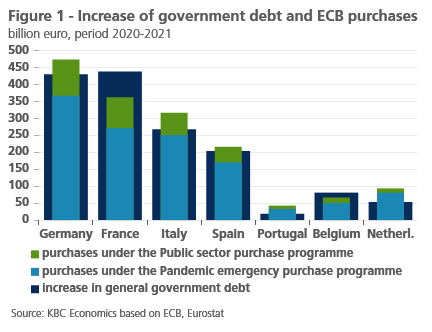

The stabilisation of the economy by fiscal policy was possible because, by invoking the General Escape Clause, the rigid European budgetary framework of the European Stability and Growth Pact was partially suspended. At the same time, the ECB, through the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) and the Public Sector Purchase Programme, purchased virtually all of the euro area’s public debt increase of nearly 1,700 billion euros in 2020-2021 (11.8% of GDP) (Figure 1). This kept market interest rates for public debt at historically low levels, which in turn ensured that, despite the sharp increase in public debt in the major euro countries, the interest burden in the budget in 2021 was not or barely higher than in 2019.

A new spring, a new tune

Those times are over. Rising inflation expectations and the growing realisation that the ECB will have to intervene sooner and more decisively than expected for a long time caused yields on 10-year German government bonds to rise from an average of -0.33% in December 2021 to almost 1% in May 2022. For the other eurozone countries, the interest rate increase was even stronger, as spreads against German Bunds more or less widened everywhere. In the major eurozone countries, the average market interest rate on 10-year government paper rose above the implicit interest rate on government debt (the average interest rate on outstanding debt) in 2021 (Figure 2). This puts upward pressure on interest costs and, if policy remains unchanged, will increase budget deficits. These were already in danger of increasing even without an increase in interest rates because of the many needs that surfaced during the pandemic, climate challenges, the digital transformation, the costs of an ageing population, and now the war in Ukraine and the need to strengthen defence.

The realisation of a new interest rate environment has probably not yet fully sunk in. At the end of April, all governments submitted their stability programmes planning for public finances up to 2025 to the European Commission (EC). In it, they assume that long-term interest rates will remain lower throughout the planning period than the levels to which they have risen in recent weeks. In that respect, the plans are already outdated. To some extent, this also applies to the EC’s recent spring forecasts, as they assume long-term interest rates for 2022 will be lower than the current level. Rising interest rates and weakening economic growth raise the spectre of a new sovereign debt crisis in the eurozone.

Storm on the way?

In the new interest rate environment, monetary policy will no longer automatically contribute to the sustainability of public finances. In a recent speech to the French High Council of Finance in Paris, the governor of the Banque de France made it clear that the fiscal authorities will have to take care of this themselves. In principle, this is done within the framework of the European Stability and Growth Pact with its numerous rules for reducing government deficits and (excessive) government debt. But, as noted above, the binding rules of these have been suspended since 2020 through the application of the General Escape Clause. The EC just proposed not to apply them yet with regard to the 2023 budgets either. According to the EC, the war, the unprecedented rise in energy prices and the continued disruption of supply chains justify the extension of the exception by another year.

The extension of the General Escape Clause has the advantage of preserving the necessary flexibility for fiscal policy to respond to economic consequences of the war situation that are difficult to predict. Moreover, there is a consensus that the budgetary rules should be simplified before they are applied in full again. Moreover, the rules on debt reduction would be too strict in the current circumstances. From this point of view, their immediate application would be problematic. But the debate on the reform is far from over. That is another reason why the extension of the General Escape Clause imposes itself.

However, this extension also entails risks. It may give the impression that the almost unlimited support of the economy from the government budget, as was the case during the Covid-19 crisis, can be continued unabated. Nothing could be further from the truth, not only because of the new monetary environment, but also because the economic shock is different now. In energy importing countries, like all euro countries, an energy price increase makes the economy as a whole less wealthy. This impoverishment cannot be borne by the government alone. This is where the energy crisis differs from the Covid-19 crisis, whose temporary economic impact could be absorbed by the government.

If so desired, the government can redistribute the loss of wealth to economic sectors or households according to what is considered socially fair. But in the current circumstances, this should not result in a boost to aggregate demand in the economy. Indeed, despite the easing of the outlook, labour markets are still relatively tight and constraints are still holding back economic supply. In such circumstances, a demand-stimulating fiscal policy would mainly fuel inflation and thus counteract monetary policy. Besides, economic growth is already being supported by the European-debt-financed NextGenerationEU.

Moreover, the extension of the General Escape Clause does not create a complete free pass for fiscal policy, certainly not for countries with a high public debt or a large structural budget deficit, such as Belgium.

Deviations from the normal budgetary rules, even under the General Escape Clause, can only be tolerated if they do not jeopardise the sustainability of public finances in the medium term. If they do, the EC can still put a member state on the penalty bench for an ‘excessive budget deficit’. The EC has indicated that it intends to do so, if necessary.

Moreover, in the new interest rate environment, financial markets will also look at government finances with a more critical eye. Already, interest rate differentials are normalising. To avoid stormy weather on the financial markets, the budget margin must be used judiciously. It allows new temporary needs to be met, for example for the reception of refugees. But new expenditure covering structural needs, such as the revaluation of certain professions and the strengthening of defence, must be budget neutral and thus offset by structural savings or new revenues.

Finally, the new monetary environment is a reminder that, as a currency union without a central stabilising budget, the euro area remains structurally vulnerable to economic shocks. The ECB cannot continue to fill that gap in a structural way, even if it signalled that it would continue to combat financial market fragmentation, for example by reinvesting its existing portfolio of government bonds “flexibly”. But the creation of a European fiscal instrument for economic stabilisation and strategic investments, as mentioned by the governor of the Bank of France in his aforementioned speech, or a stabilisation fund, as proposed by the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) in a recent discussion paper, would be a purer solution to prevent or cushion eventual storms.