QE 2.0 and inflation: this time it’s different

The major central banks reacted to the Covid-19 pandemic as they did to the global financial crisis and the European debt crisis: with a new round of large-scale quantitative easing. These prior rounds of liquidity creation mainly stabilised the financial sector and boosted only to a limited extent the demand for goods and services in the real economy. Consequently, they did not lead to the inflationary upsurge feared by some economists, but rather the contrary. Against this backdrop, some economists now argue that the current round of quantitative easing will not be as buoyant in terms of inflation. However, there are now important differences: the explicit coordination of expansionary monetary and budgetary policies, the increased inflationary appetite of central banks, the trend towards deglobalisation and disruption of international production chains, and the role that higher inflation is likely to play in tackling the overall debt problem. In the longer term, the era of (very) low inflation could give way to a period of persistently higher inflation.

The macroeconomic policy response to the Covid-19 pandemic was unprecedented. In the US and the eurozone, it was not only the fiscal side that launched stimulus programmes on an unprecedented scale. The ECB and the Fed also played their part. In addition to the existing Asset Purchase Programme, the ECB launched a new purchase programme, the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP). In March 2020, the Fed even stated unequivocally that it would intervene in the bond market for any amount of money needed to safeguard the stability of the economy.

The nature and extent of these measures is remarkable. With the PEPP, the ECB is abandoning the traditional government bond purchase key, thus paving the way for targeted monetary financing of specific Member States in financial difficulties. The Fed’s “whatever it takes” kind of promise also creates a completely new dimension to US monetary policy. This applies to both the timing and the order of magnitude. Our interpretation is that this is probably tantamount to monetary financing of fiscal stimulus, without saying so explicitly.

Impact on inflation

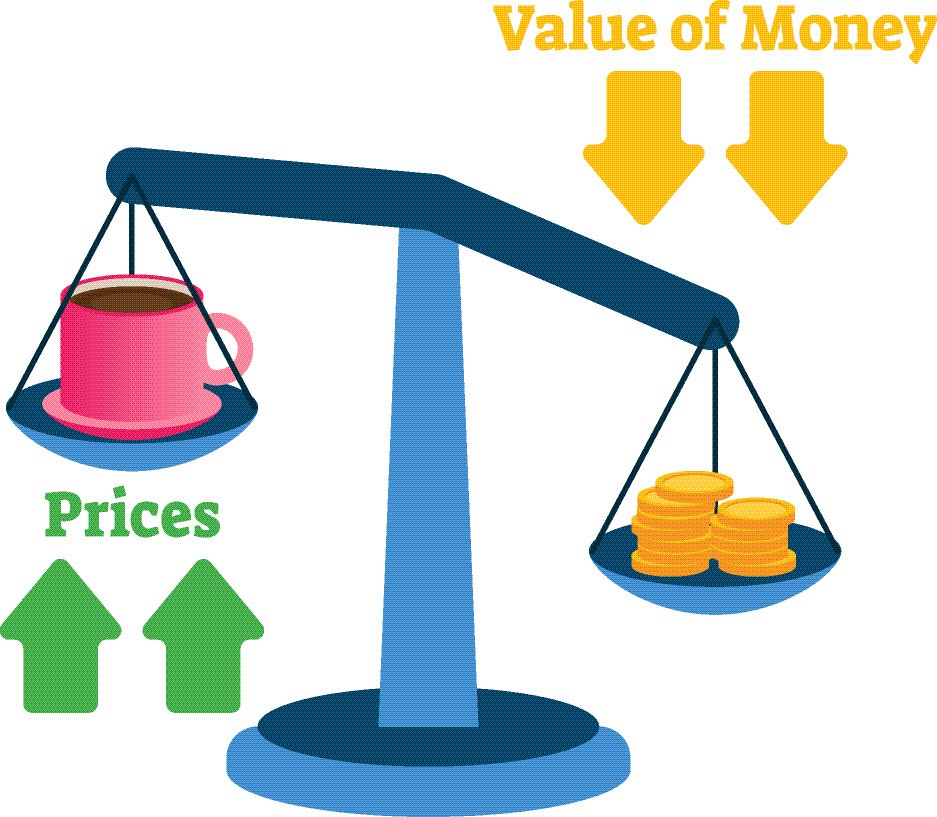

Against this background, it is important to reflect for a moment on the longer-term consequences. There is a broad consensus that monetary measures during the Covid-19 pandemic are necessary in the short term. In the longer term, however, this new round of QE is likely to lead to higher inflation. This is not necessarily a bad thing. After all, as a solution to the globally growing mountain of debt, debt securities are initially ‘parked’ on the balance sheets of central banks. If, in the longer term, higher inflation causes the real value of those debts to fall, that would be convenient as well.

It is often argued that the first round of quantitative easing has not led to an inflation surge (on the contrary), and that this will therefore not be a problem with the current QE 2.0 either. However, there is now a clear difference. Figure 1 shows the development of the broad money supply (M2), which effectively enters the real economy and is used to buy goods and services, thereby affecting inflation. During the first QE round, M2 did not grow excessively. The enormous amount of liquidity that the central banks pumped into the market at that time remained largely within the financial sector and hardly ever ended up in the real economy. That is one of the reasons why inflation remained so stubbornly low.

This time it is different

The current picture is different. In the US, the year-on-year growth rate of the broad money supply is now more than 20%, which is by far the highest growth rate in recent decades. In the euro area, this growth rate is still much lower, but an upward trend is also visible. An important explanation for this is the current strong coordination of monetary and budgetary policies. Indeed, the liquidity created does not now serve to stabilise the financial sector, but rather finds its way into the real economy without major obstacles, among other things through government spending. This stimulates demand for goods and services and supports inflation.

The time horizon considered is important. In the short term, the Covid-19 shock will first cause low inflation worldwide. After all, it will take some time before economic activity reaches its pre-Covid-19 level again. Thereafter, however, inflation will gradually increase. For 2023, we expect inflation to be 2.1% and 1.3% for the US and the euro area respectively, which is still moderate compared to the central banks’ targets.

This will happen at a time when the inflation appetite of central banks has also increased. From now on, the Fed’s updated policy strategy explicitly pursues an average inflation target of 2%. This means that, as far as the Fed is concerned, a period of lower inflation should be followed by a period of higher price increases. The ECB is also inclined in this direction. Although it will probably not complete its own strategy update until the second half of 2021, we already have an idea of the direction the new inflation target will take. In her press releases, ECB President Lagarde already systematically refers to a desired symmetry around the target inflation. In the longer term (roughly from the mid-2020s onwards), the ECB too would probably be willing to tolerate a temporary ‘overshooting’ of inflation in the euro area above 2%.

How long can such an ‘inflation overshooting’ last, and how far can it go? Firstly, it depends on the communication of the central bank itself. After all, an objective of ‘average inflation’ is vague. It is not entirely clear over which period the central bank calculates that average. In addition, this can create uncertainty for financial markets in shaping their inflation expectations. If the uncertainty causes inflation expectations to rise sharply, there is a risk that the effective ‘inflation overshooting’ will also be much more substantial and protracted. In the longer term, the current era of low inflation could give way to a period of persistently higher inflation