Beyond Brexit: Land of Hope and Glory for international investors

The uncertainty surrounding the Brexit negotiations has put substantial pressure on the British economy. The British current account deficit in particular has widened substantially. Nevertheless, foreign investors have kept their trust in the UK economy. International investments in the UK are flourishing despite weakening domestic investments. Not only strategies to evade trade barriers, but also the post-Brexit outlook of low taxes and a growing market are currently boosting international investments in the UK.

Growing imbalances

In 2016, the UK current account deficit reached a record high of 5.9% of GDP (ONS 2017). Many blame Brexit for this deterioration, but that is only partly true. One reason for the increasing current account deficit is the growing trade deficit (2.2% of GDP). Total UK imports of goods and services have exceeded total exports for many years. This is mainly due to the weak UK export performance in manufacturing products, strongly driven by a general trend of deindustrialisation in the UK. Goods previously produced domestically have increasingly been substituted by imported ones. The strong export performance of the service sector has only partially compensated for this so the trade balance has tilted into the red. This deindustrialisation trend started long before the Brexit debate. Hence, Brexit is not the main driving force. The British trade balance deteriorated further after the Brexit referendum in June 2016. Despite the positive export growth, thanks to the depreciation of the GBP that improved the competitiveness of British exporters on international markets, import growth accelerated faster. The latter again is a consequence of the deindustrialisation process. Despite the higher prices for imported products, expressed in GBP, British import demand have remained relatively stable as domestic alternatives were often not available. Particularly in the short run, production processes are sticky and cannot adapt to the new situation. In the longer run, the British industrial sector could get a boost, at least if products can be produced cheaper in the UK than elsewhere. This is the ultimate dream of many brexiteers. Such a re-industrialisation would be a tremendous challenge though. Even regardless of Brexit, an industrial revival of the UK would be welcome to solve the structurally unbalanced trade position.

A second reason for the deterioration of the UK current account balance is the widening primary income deficit (2.6% of GDP). The latter is mainly due to a deterioration in the net earnings on direct investments. For more than a decade, the UK’s earnings on direct investments abroad exceeded foreign investors’ returns on their UK investments. As such, the positive primary income balance offered some compensation for the trade deficit as well as for the traditionally negative net earnings on portfolio investments (due to the UK’s role as global financial centre). Since 2011 earnings on foreign direct investments by UK companies have declined, while earnings on foreign direct investments in the UK have remained constant thanks to the flourishing British economy. Moreover, rates of return on both inward and outward investments have been declining over the last decade, but the decline in the rate of return on UK investments abroad has been more pronounced. Very interesting is the observation that the deterioration in the primary income balance is being caused by a worsening of the UK’s deficit towards non-EU countries, whereas the UK’s deficit towards EU countries has shrunk in recent years. In 2016, net earnings on direct investments became negative for the first time. The latter is again mainly a consequence of the depreciation in Sterling as the conversion of foreign–currency-denominated international receipts into Sterling reduces the value of British investors’ foreign earnings. The opposite happens for international investors’ earnings converted from Sterling into most other international currencies. Hence the primary income deficit part of the current account deficit is clearly related to Brexit, or more precisely the depreciation in Sterling after the Brexit referendum, on top of structural factors.

Looking beyond the short run

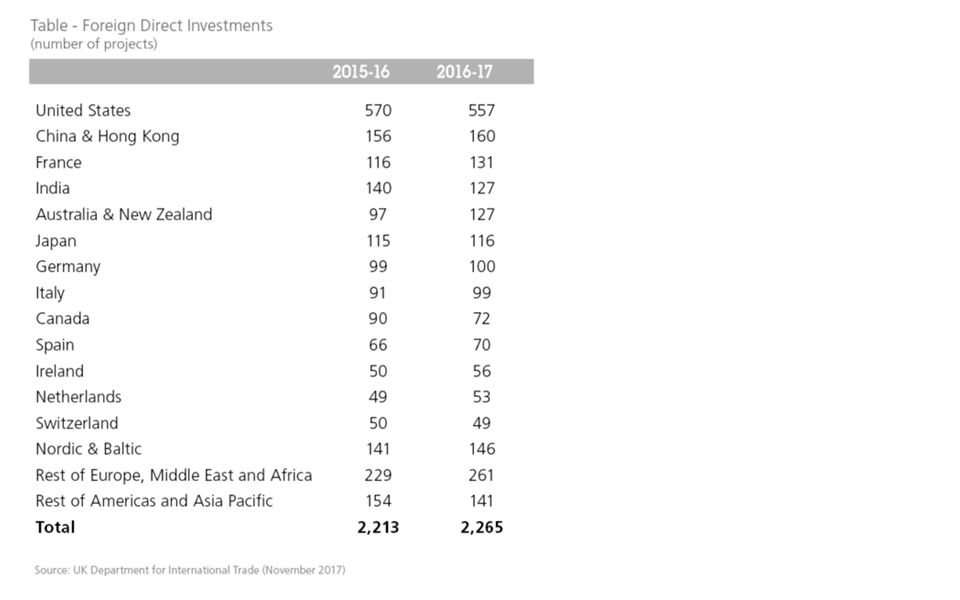

The current account deficit is likely to widen in 2017 too. First, because the further depreciation of Sterling continues to strengthen the mechanisms described above. Second, because foreign investors are keeping up their investments in the UK. The latter may seem surprising. Despite the uncertainty surrounding the Brexit negotiations, international direct investments in the UK continue to grow. Recent figures published by the UK Department for International Trade indicate that the number of foreign investment projects in the UK in the period 2016-2017 increased compared to the same period in 2015-2016 (see Table). Even more surprisingly, the growth in foreign direct investments is taking place despite declining growth in domestic investments. Hence Brexit appears to be having an opposite effect on British and international investors, at least for now.

Why is this happening? Brexit is forcing companies to evaluate their business strategies. This holds for British as well as international firms. The public debate is strongly focused on the potential relocation of British firms seeking continued access to the EU single market. However, the opposite is also happening. Many EU firms are currently investing in the UK to safeguard their access to the British market in the long run, whatever the outcome of the Brexit negotiations will be. Firms from many, in particular EU, countries are implementing such strategies (see Table). After all, the UK is a large market with an upward demographic trend and a high geographical proximity. Such a business strategy is sometimes called a tariff-jumping strategy. In this case, it could also be called a Brexit-jumping strategy as firms avoid the full blunt and uncertainty of Brexit by moving into the UK.

On top of that, the British economy is flexible due to its strongly deregulated labour market and the British government intends to take a generous stance in international tax competition. As a consequence, corporate taxes as well as labour costs will be low compared to elsewhere in the EU. This will make the UK an attractive market for sales as well as production. To the extent that foreign investors are active in the manufacturing sector, the revival of British industry may well be achieved by international players rather than through a domestic re-industrialisation.

Hence the main lesson from recent developments in the British economy is that the UK remains a very interesting business partner. Many international investors clearly believe that the post-Brexit future will be bright, despite the many challenges the UK-EU divorce will bring along. Ultimately, market size and geographic proximity are such fundamental determinants of international business relations that no political decision can put them on hold.