New TTIP: Worthy alternative to a trade war

The transatlantic trade relationship remains one of the strongest and most differentiated in the world, despite the impressive rise of emerging economies. There is a risk that the current tensions due to increasing US protectionism could be met with a comparable protectionism in Europe. However, this would constitute a historic mistake. Europe is within its rights to, and should, take a resilient stance and threatening countermeasures in order to limit unilateral US trade restrictions. However, at the same time, the EU should offer the United States an alternative, in the form of increased integration and cooperation in trade and investment. In other words: give the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) a second chance!

Twin Deficit

US President Donald Trump is facing the twofold problem of a rising public deficit and a growing trade deficit, a phenomenon known as a ‘twin deficit’. He is partially responsible for the first of the two. The US government and Congress, the latter controlled by Republicans, are advocates of strong fiscal incentives. They hope to keep the American economic engine running through tax cuts and public investments, despite this being one of the longest periods of economic growth ever recorded. From an economic point of view, these are useful measures, of which we can only dream in Europe. But at the same time, the timing of this policy is seriously questionable. The US economy is at risk of overheating and public finance is becoming unsustainable.

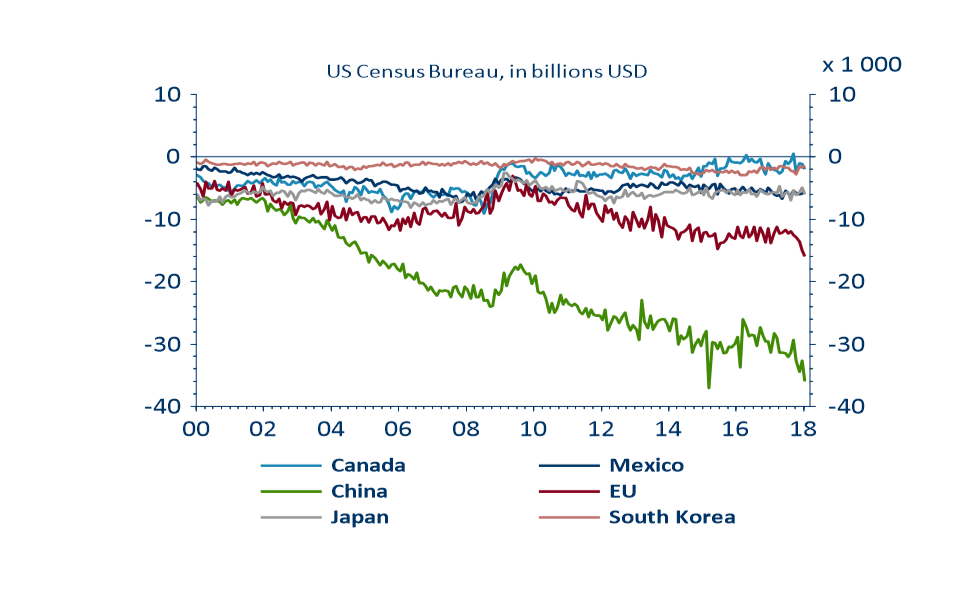

The second half of the twin deficit, the significant and increasing trade deficit (568 billion USD in 2017), is far less a consequence of US domestic policy. In itself, a trade deficit is not a problem, but the reasons behind it are. Extensive globalisation has resulted in many foreign exporters operating in the vast US market. Emerging economies such as China and South American countries in particular, have gained a foothold in the US economy. And yet, American policy measures do play a part in these developments. America’s strong economic performance is largely the result of a sharp growth in consumer spending. Combined with far-reaching de-industrialisation, there is now a large demand for foreign imports in the consumption-oriented society. This is leading to an increasing trade deficit with all the important trade partners (see figure).

Figure 1 - Trade balance US with most important trade partners (in billion USD)

Source: US Census Bureau

The US de-industrialisation indicates that successive US governments have failed to invest sufficiently in the international competitive strength of industrial sectors. This has led to a downturn in export performances in many sectors. The export growth in services has only been able to partially compensate for this. So, the US trade deficit is a consequence of both increasing imports and weak export performances.

Trump and Louis XIV

Trumps reactie op het toenemend handelsbalanstekort is zeker begrijpelijk. Om het evenwicht te herstellen is het in principe een optie om de import te beperken. Er zijn zeker valabele economische argumenten om te stellen dat het handelsbeleid van bepaalde opkomende economieën, en in het bijzonder van China, niet in overeenstemming is met de spelregels van de Wereldhandelsorganisatie. Exporteren naar China wordt bemoeilijkt door systematische discriminatie van buitenlandse producenten, administratieve beslommeringen (red tape) en een gebrekkige bescherming van intellectuele eigendom. Bovendien wordt de Chinese export op een niet-marktconforme manier gestimuleerd via productie- en exportsubsidies. Terecht reageren zowel de VS als de EU hierop via trade defense reacties: anti-dumpingmaatregelen evenals anti subsidiemaatregelen worden intensief aangewend om de oneerlijke Chinese handelspraktijken aan te pakken. Dergelijk beleid is conform de regels van de Wereldhandelsorganisatie. Toch is het duidelijk dat deze aanpak onvoldoende effectief is. Het blijft dus beter om de oneerlijke Chinese handelspraktijken aan te pakken via internationale onderhandelingen, bij voorkeur in een multilateraal kader, in plaats van te reageren met protectionistische maatregelen.

New TTIP: a courageous European response

Trump’s response to the increasing trade deficit is certainly understandable. Restricting imports is indeed one way to restore the balance. Certainly, there are valid economic arguments for asserting that the trade policies of some emerging economies – China in particular – flout the rules set by the World Trade Organisation. Exports to China are thwarted by systematic discrimination of foreign producers, bureaucratic red tape and inadequate protection of intellectual property rights. Moreover, Chinese exports are boosted in a way that is not market-based, through production and export subsidies. Rightly, both the US and the EU have reacted to this with trade defence responses: anti-dumping measures and anti-subsidy measures are both liberally applied in efforts to combat China’s unfair trade practices. Such policy is in line with World Trade Organisation rules. However, this approach is clearly not effective enough. It would therefore be better to tackle these unfair trade practices through international negotiations, preferably in a multilateral framework, instead of responding with protectionist measures.

Protectionist responses reflect a fundamental error in the attitude towards trade: the belief that export is ‘good’ and import is ‘bad’. As far back as the 17th century, French ‘Sun King’, Louis XIV, stated that he was in favour of more French exports because they generated gold, and against imports because they cost France gold. The Trump administration’s current measures uncannily echo the French Sun King’s trade policies. Nevertheless, imports generate an important increase in prosperity, in the shape of lower prices, improved choice for consumers and businesses and reductions in production factors, etc. Conversely, a restriction on imports leads to a loss of prosperity.

Structural trade deficits should be adjusted. Macroeconomic imbalances disrupt international economic relations and stability in the long term. But rather than restricting imports, we can also tackle a trade deficit by stimulating exports. And that’s where the US and the EU could be each other’s friends instead of foes.