Mandatory recapitalisation threatens independence of Swedish Riksbank

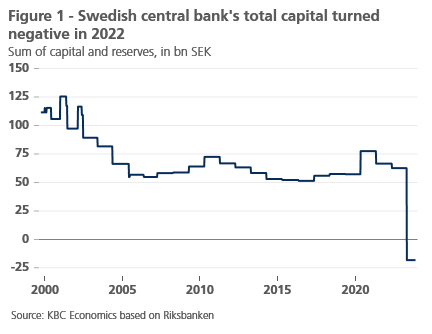

The Swedish central bank (Riksbank) made an accounting loss of about SEK 80 billion in 2022 due to non-realised losses on its bond portfolio. As a result, its capital fell below the critical threshold of SEK 20 billion and even became negative. According to its new statutes, the central bank must now apply to parliament for recapitalisation. That automatism is problematic. After all, it compromises the central bank's independence. There is a danger that the central bank could be distracted from its objective of price stability by paying undue attention to the impact on its annual profit and loss (P&L) account. After all, because of its monopoly on currency issuance, a central bank is not a standard firm. Therefore, there is no operational reason to impose, as in Sweden, an immediate recapitalisation in case of capital that is ‘too low’. The modus operandi of the Fed and the ECB is sounder: both central banks account any losses (in the case of the ECB, this concerns its monetary policy portfolios) only when they are effectively realised. That avoids pure accounting losses. Moreover, transfers by the Fed to the Treasury in case of losses are simply suspended until these losses are compensated by subsequent profits, without recapitalization in the meantime. The statutes of the ECB do not provide for automatic recapitalisation either, but negative ECB capital has not occurred so far. However, due to its supranational nature, such a political discussion would be more sensitive than in the US. In any case, ECB President Lagarde recently confirmed that ECB monetary policy should only focus on price stability, and not be distracted by the impact on the ECB’s P&L account.

Since 2023, the statutes of the Swedish central bank (Riksbank) have been updated. An important new element is that the central bank must request recapitalisation from parliament when its capital falls below a certain threshold. That value is indexed annually to inflation and currently amounts to SEK 20 billion. A recapitalisation is in principle done at least up to the base value (currently SEK 40 billion), unless the Riksbank or parliament deems it necessary to recapitalise up to the reference value (currently SEK 60 billion). The amount of capital that rises above that reference value must be paid out to the Treasury.

On 24 October of this year, Riksbank Governor Thedéen announced that this new rule will already apply to the most recent 2022 financial statement. In 2022, the Swedish central bank made an accounting loss of SEK 81 billion, reducing its capital to SEK -18 billion (about 0.3% of GDP) (Figure 1). The increased interest rates caused unrealised losses on the Riksbank’s bond portfolio, which it previously accumulated under its policy of quantitative easing. As a result of the now insufficient capital, the Riksbank will request recapitalisation from parliament in early 2024. In addition, the Riksbank would look at possibilities to generate additional future income to ‘improve’ its P&L account.

Independence under threat

This statutory obligation is problematic in principle. After all, negative capital of a central bank is generally not a problem (see KBC Economic Opinion of April 17, 2023). As part of the consolidated government and with their monopoly on issuing currency, central banks are not standard firms. This argument was already raised in 2010 by the Czech National Bank in a discussion with the ECB. A problem could only arise in the extreme situation in which even all discounted future profits ('seignorage') would not be sufficient to offset losses incurred in the past. Apart from that, there is no reason to prohibit temporary negative capital for a central bank, as is currently the case in Sweden.

On the contrary, such a mandatory recapitalisation puts the central bank in a position of dependency on the fiscal authorities. The Swedish parliament will approve the recapitalisation in accordance with the statute, but politicians do have an indirect means of pressure vis-à-vis the governor. After all, the governor depends on the politically appointed General Council of the Riksbank for his or her possible reappointment, and in extremis can even be ousted by the same General Council. The governor's (economically dangerous) quest for additional future revenue for the Riksbank is probably already partly motivated by this implicit political pressure.

Stigmatising a central bank's accounting loss and negative capital may result in the central bank not pursuing the ‘first-best’ policy in pursuit of price stability, because it has to take into account the impact on its P&L account. An example would be a central bank not raising its policy rate sufficiently for fear of causing unrealised losses on its bond portfolio as a result. This could jeopardise the objective of price stability. ECB President Lagarde insisted at her press conference of 26 October that “[a]s the Eurosystem and as ECB, we have one mission and that is price stability and we do not have as a purpose to show profits or to cover losses and it would be actually wrong if our decisions were guided by our P&L accounts […]”.

Better alternatives

Different central banks have their own arrangements for sharing with their national treasuries both QE-related past profits and future losses. In the end, however, the financial results always end up with their national governments, which are usually the central banks' only final shareholders (a number of central banks, including the National Bank of Belgium, also have private shareholders). However, exactly how and when these transfers occur depends on the specific accounting rules in the specific country.

In that context, the statutes of the Fed and the ECB safeguard their independence. The Fed does not consider unrealised capital valuation losses, taking into account only the market value at the effective sale of assets. Similarly, at the ECB, assets from its monetary policy portfolios are not valued at market value. Moreover, realised losses by the Fed are reflected accounting-wise as a ‘deferred asset’ i.e., the amount of net profit that the Fed must first generate before future transfers to the US Treasury can take place again. The ECB's statutes do not provide for automatic recapitalisation in the event of negative capital either. However, that case has never occurred so far for the ECB. The supranational nature of the ECB would probably make such a discussion more politically sensitive than in the US.