Italy after elections: new government, same plan?

In Italy, the leader of the only opposition party to the resigned Draghi government has the best chance of becoming prime minister after the parliamentary elections on Sunday 25 September 2022, according to opinion polls. Draghi was the architect of Italy’s Plan for Recovery and Resilience. That plan should help eliminate the Italian economy’s growth deficit - the Achilles heel of its sky-high public debt. So, if the new prime minister does not want to jeopardise the sustainability of Italy’s public finances, she has every interest in taking the plan forward. Substantial EU financial support as well as the fact that fulfilment of the plan is a condition for the ECB’s new Transmission Protection Instrument are powerful incentives to do so.

Italy will elect a new parliament on Sunday. This is likely to end the political career of current prime minister and former ECB president Mario Draghi. He entered the political forum in February 2021 after the fragile then governing coalition failed to produce a Next Generation EU Recovery and Resilience Plan. Italy risked missing out on almost €200 billion (10.8% of GDP) of European grants and loans, as well as a unique opportunity for much-needed economic reforms. As the head of a national unity government - only Fratelli d’Italia did not participate - Draghi was able to prevent that outcome. Using EU financial support as bait, a plan with no less than 527 targets and milestones was launched.

Growth deficit

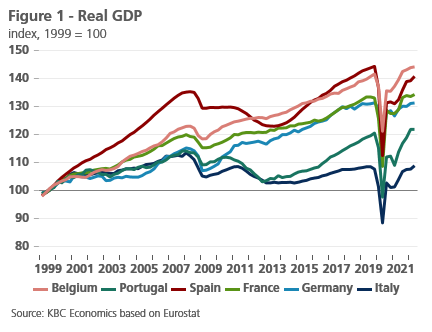

Those reforms are much needed to keep public debt under control. After Greece, Italy has the highest public debt in the eurozone as a percentage of GDP: 152.6% of GDP in the first quarter of 2022. As in almost all countries, the Covid-19 crisis caused a sharp increase in public debt. Meanwhile, it appears that, all in all, the Italian economy came through the Covid-19 crisis reasonably well. Real GDP in the second quarter of 2022 was 1.1% higher than before the pandemic. This is a somewhat weaker recovery than in Belgium, but comparable to France and Portugal, and significantly better than in Spain and even Germany.

However, the relatively strong growth recovery after the Covid-19 crisis is only meagre consolation in light of the underperformance of the Italian economy since the turn of the century (Figure 1). Already in the first decade, it lagged behind that of many other European countries. In the previous decade, the lag increased. At the outbreak of the pandemic in early 2020, the economy had still not returned to the level of early 2008, just before the financial crisis. That structurally weak economic growth is the Achilles’ heel of Italy’s public finances, especially as the Italian economy is particularly vulnerable today due to the energy crisis.

Snowball effect

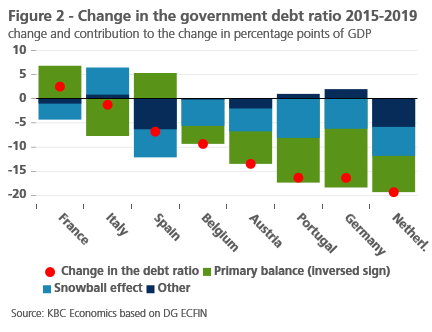

Figure 2 shows the change in the government debt ratio in the (medium-)large eurozone economies during the relatively benign economic period before the pandemic (2015-2019). In almost all countries shown, the debt ratio fell quite sharply at that time, but hardly at all in Italy. Only France fared worse with an increase.

Changes in the debt ratio are mainly determined by the primary budget balance (the balance excluding interest charges on government debt) and interest charges, both expressed as a percentage of GDP. In addition, other factors, including asset purchases or sales, play a role. The primary fiscal balance is determined by policy and the impact of the business cycle. The change in the ratio of interest expenses to GDP depends on the change in the debt ratio in the previous year, on the change in the average interest rate on outstanding debt (the implicit interest rate) and on nominal GDP growth. The interplay between nominal GDP growth and the implicit interest rate creates the snowball effect. If growth is higher than the implicit interest rate, it creates a downward effect on the debt ratio. If growth is lower than the interest rate, there is upward pressure.

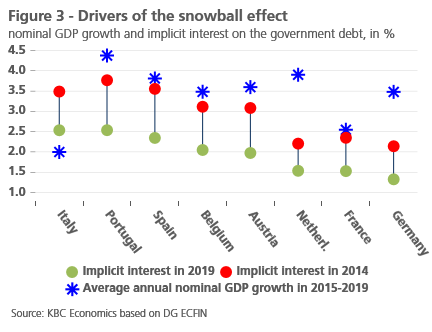

Figure 2 also shows that in the relatively benign economic period shown, Italy was the only country that continued to suffer from an adverse snowball effect. It almost completely neutralised the downward effect of primary budget surpluses on the debt ratio. However, those surpluses were significant. Only in Germany and Portugal were they larger (as a percentage of GDP), while in Belgium they were much smaller and France even accumulated deficits. The negative snowball effect in Italy was mainly due to low nominal economic growth (Figure 3). While the implicit interest rate on government debt remained among the highest of the countries shown, it fell to a historic low, as was the case everywhere, driven by low inflation and European Central Bank policies. However, as ever, economic growth remained far behind all other countries.

This underlines the need to strengthen the growth potential of the Italian economy. Further implementation of the Recovery and Resilience Plan can help in this regard. Only 10% of it has been achieved, according to the European Commission’s scoreboard. If the leader of the only opposition party becomes prime minister - according to opinion polls, that chance is high - she will have every interest in further implementing the plan, at least if she does not want to jeopardise the sustainability of public finances. The sizeable EU financial support (more than 70% has not yet been disbursed) could be a powerful incentive to do so, as could the fact that the ECB has made the use of its new Transmission Protection Instrument conditional, among other things, on the member state concerned meeting the commitments in the recovery plan.