Italy shoots itself (and the euro area) in the foot

The results of the recent Italian elections render further economic reforms all but impossible. In voting as they did, the Italians have shot themselves in the foot, as their future prosperity is now in jeopardy. And without structural economic improvement, Italy also continues to pose a latent threat to the euro area. It is, after all, the third biggest economy in the monetary union, with the largest absolute public sector debt. The risk of potentially colossal financial support will hinder the structural reinforcement of the euro area envisaged by the Merkel-Macron axis. In this way, the election result has shot Europe in the foot too, by complicating plans to bolster the euro area.

Observers were more or less unanimous in their predictions that the Italian parliamentary elections on 4 March would produce a far from workable outcome. Unfortunately, the actual result was worse than even the most pessimistic had predicted. It is not clear how a political majority can be achieved in either house of parliament. The two main populist parties – the anti-establishment Five Star movement and the Lega (formerly the separatist Lega Nord, which has formed a centre-right bloc with ex-premier Silvio Berlusconi), persuaded half of the electorate to vote for them, with an unaffordable programme of tax cuts and government spending. Although they have toned down their anti-European rhetoric, these parties remain relatively hostile to European integration. The pro-European, centre-left Democratic party of the reformist former prime minister Matteo Renzi and the departing premier Paolo Gentiloni lost more than half of its seats, making it virtually impossible to form a centrist government.

For the time being, the financial markets are not unduly worried about the political impasse. The risk premium – traditionally measured as the difference betwen the return on ten-year Italian and German government paper – is only 30–40 basis points higher than it was three years ago at the bottom of the euro crisis. Political instability has generally been an Italian hallmark: in the present republic’s 71-year history, it has had 64 governments, with five in the past seven years. The country is more or less used, in other words, to not being governed. This might sound reassuring, but such ungovernability comes at a high economic cost.

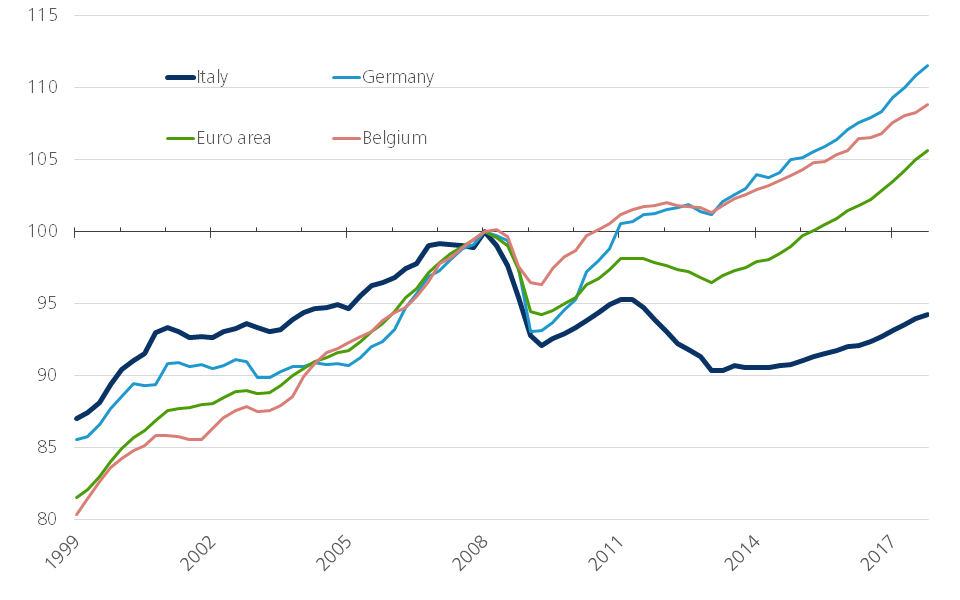

Economic growth has picked up in Italy in recent years, as elsewhere in the euro area, but it has lagged far behind other countries. Real GDP was still 5.5% lower in 2017 than its pre-crisis peak ten years earlier. For the euro area as a whole, by contrast, real GDP was 5.5% higher (Figure 1). Weak economic growth is not a recent phenomenon for Italy: in the ten years between the introduction of the euro in 1999 and the beginning of the financial crisis in 2008, GDP growth there averaged barely 1.2% a year, compared to 2.1% in the euro area. As a consequence, real Italian GDP is only slightly higher today than it was at the turn of the century, during which period economic prosperity in the other euro countries has risen by an average of 20% and as much as 26% in Belgium.

Figure 1 - Real GDP (Q1 2008 = 100)

Source: KBC Economic Research based on Eurostat (2018)

The long-standing problem of weak economic growth stems largely from crumbling Italian productivity. This has many causes, not least a poorly functioning labour market, with its gulf between overly protected permanent jobs and an exaggerated stress on insufficiently protected temporary jobs. By wrongly focusing on unemployment policy, public resources are more likely to be deployed keeping people in unproductive jobs than helping them find new, productive employment. Other structural weaknesses include ineffective government and regulation.

The then premier Matteo Renzi pushed through broad structural reforms in 2015, including a new electoral law, more modern government, more efficient courts, better-performing education and above all large-scale labour market reforms. In late 2016, however, he lost a constitutional referendum, as a result of which the implementation of his reforms faces serious problems. The latter dominated the agenda of the departing premier, Paolo Gentiloni, and are now on the new government’s desk.

Italy still has a long way to go in order to strengthen its economy. Unemployment may be falling, but it remains at record levels – significantly higher than the euro area average, while labour market participation is among the lowest in the EU. The deterioration in Italy’s cost competitiveness has stopped, but there is no question yet of a recovery. Fortunately, the banking sector is recovering and the long-standing problem of non-performing bank loans is finally being tackled. Substantial challenges remain in the area of government finances. Italy has the second highest public-sector debt (measured as a percentage of GDP) in the EU after Greece, while its budget deficit is structurally deteriorating.

Italy is unlikely to wind up in an acute funding crisis in the immediate future. Unlike France, for example, it does not have a deficit on the balance-of-payments current account and Italy’s net investment position only shows a small external deficit. Italians save enough to fund their public debt themselves, which mitigates the risk.

The problem is more that the election result makes it impossible to form a stable government with a sufficiently strong majority to continue the reform process. Italy is caught – more so probably than other countries – in a vicious economic, social and political circle. Declining productivity in recent decades is expressed in real per capita disposable income, which is now lower than it was 20 years ago. The younger generation and wage-earners in particular have suffered a relatively sharp fall in income, while retired and older people have generally been shielded (Banca d’Italia, 2015). This creates a hotbed for political fragmentation and populist policy measures. It has produced election results that make it impossible to strengthen growth and prosperity, leaving the hotbed intact.

The failure of strong growth to materialise will be expressed over time in higher risk premiums on the public debt, certainly when the ECB ends its government bond purchasing programme. The sustainability of the higher public debt will move back into the foreground as interest rates rise. In the absence of stronger growth, Italy will remain a potential threat to the stability of the euro area. As the third largest economy, it is after all too big to bail out, should it yet find itself in a funding crisis. Smaller countries like Greece and Portugal were still manageable. Consequently, without reform, Italy will continue to pose a systemic risk to the euro area. The latent threat of potentially colossal financial support will hinder the structural reinforcement of the euro area as envisaged by the Merkel-Macron axis. In order to be effective, this would require the creation of better financial support mechanisms and any such steps would only be likely if member states themselves were pursing a policy that mitigated their necessity.

In short, Italy has not only shot itself in the foot by putting its own prosperity in jeopardy, it has also done so to the euro area, by making it harder for it to strengthen itself.