Italian government plays with fire

A year after a populist government took office, the economic consequences for Italy are clear. Economic growth has come to a standstill and interest rates on government paper remain higher than in almost all other euro countries. This is the price Italy is already paying for unorthodox policy. In the long run, this price threatens to rise, because with relatively weak growth and relatively high interest rates, the interest snowball will enlarge the public debt. In that respect, the government is playing with fire. In the meantime, current policies do nothing to strengthen the growth potential of the economy.

Towards an excessive budget deficit...

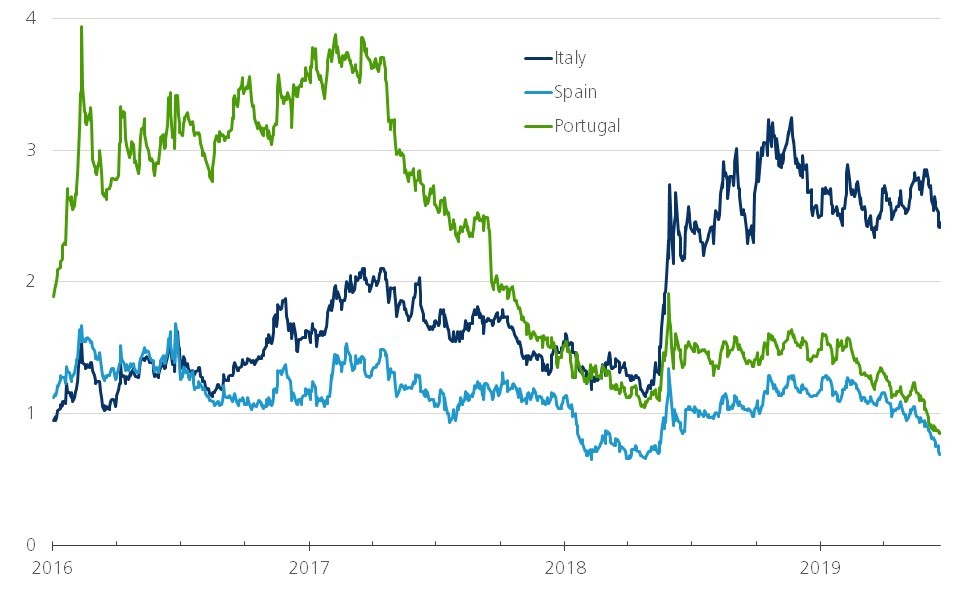

Long-term interest rates are looking for new lows in the eurozone. But in Italy, the yield on ten-year government bonds as of mid-June was still a full percentage point above its previous low. Despite the recent decline, at just over 2% it remained around 250 basis points higher than the yield on a German Bund with the same maturity (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Risk premium on Italian government bonds remains high (bond yield spread to 10 year German Bund, in percentage points)

The risk premium on Italian government bonds has fluctuated around that level since the current government took office in June 2018. It is a coalition of two populist parties that together achieved a parliamentary majority in the March 2018 elections. It wants to boost economic growth with tax cuts and government spending. It has already cut back on previous economic reforms.

At the end of 2018, the government reached a difficult compromise with the European Commission (EC) that would limit the budget deficit to 2.04% of GDP in 2019. However, according to the EC’s recent spring forecast (May 2019), the deficit will rise to 2.5% of GDP in 2019 and to 3.5% in 2020. This is well above the 3% threshold of EU fiscal rules. According to the EC forecasts, Italy is the only euro area country where the government debt ratio - the second highest in the euro area after Greece - will not have fallen by 2020. The budget is also moving in the wrong direction according to other yardsticks. As a result, the EC decided that Italy qualifies for closer European supervision through an “excessive deficit procedure”.

... and an economic failure

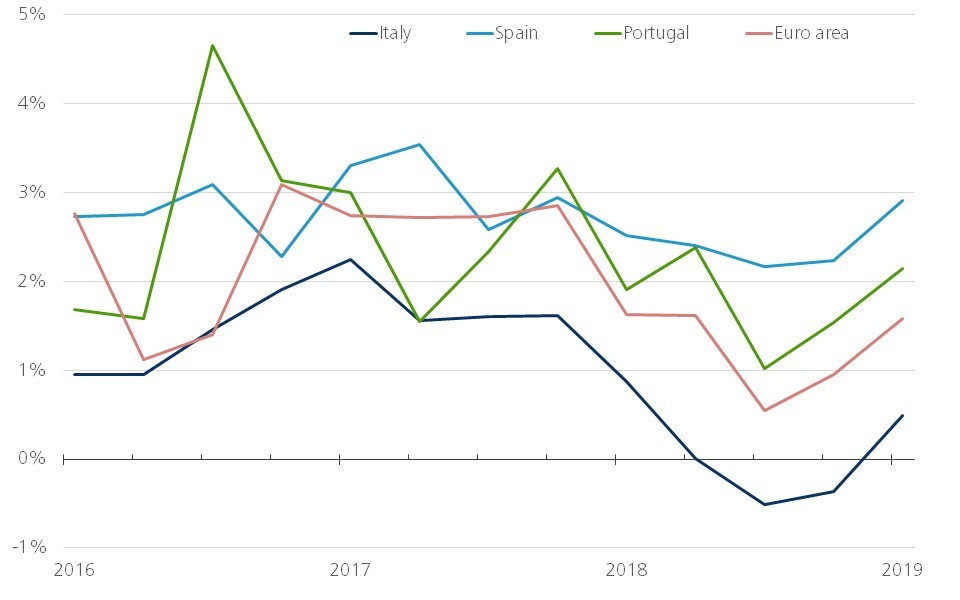

Before next steps are taken, many more political waters will be navigated. From an economic point of view, it is clear that Italy is a long way from achieving the desired result. Instead of accelerating, economic growth came to a complete halt in 2018. After stagnation in the second quarter, the economy fell into recession in the second half of the year (figure 2).

Figure 2 - Italian economy turned into recession (quarter-on-quarter change of real GDP, annualised, in percentage)

Together with the economic slowdown in Germany, this was the main cause of disappointing growth in the eurozone. Italy is also experiencing the negative impact of, among other things, US trade policy and Brexit on the European economy. However, a comparison with growth in Spain and Portugal suggests that there is much more going on in Italy. The export openness of Spain and Portugal is greater than that of Italy. In principle, both countries are therefore more vulnerable to the deterioration of the international economic climate. Nevertheless, relative to Italy, economic growth in those countries slowed down much less in 2018 and recovered more strongly in early 2019. The growth of the Spanish economy is particularly impressive compared to the economic stagnation in Italy.

Weak economic growth in Italy is not a recent phenomenon. In the 10 years between the introduction of the euro in 1999 and the outbreak of the financial crisis in 2008, real GDP growth averaged barely 1.2% per year, compared to 2.1% in the euro area. Real GDP in Italy today is barely higher than at the turn of the century, while economic prosperity in the euro area has increased by 25% on average. Unemployment in Italy is among the highest in the euro area and is currently declining more slowly than in Spain and Portugal.

Missing the point

The diagnosis of the need to bolster economic growth in Italy is therefore correct. But when it comes to the remedy, the government is missing the point. The growth problem is the result of a lack of competitiveness and structural economic renewal. This will not be solved by a policy of mainly stimulating demand. It requires a strengthening of the supply side. In addition to reforming regulations and institutions, this requires investment. Investment, in turn, requires economic confidence. But the government has undermined this. It is therefore indeed painful, but not surprising that investment has come to a standstill. Compared to other euro countries, this is typically Italian (figure 3).

Figure 3 - Stalling investments in Italy (gross fixed capital formation, excl. construction, volume index, Q1 2008 = 100)

Moreover, current policy is risky. In most euro countries, the fall in the government’s debt ratio is mainly the result of (nominal) economic growth that is higher than the interest rate on the debt. In these circumstances, it is usually sufficient to keep the budget deficit, excluding interest expenditures, stable. In Italy, interest rates are higher than economic growth, with the result that the debt is driven up by the so-called interest snowball. Policy choices are partly responsible for this because they keep the risk premium in the interest rate high and undermine growth. Already today, no EU country spends more on interest charges in relation to GDP. This money is not available, for example, for education or other investments that enhance growth potential. All in all, the risk premium is still limited. The Greek example illustrates that much higher premiums are possible. Given the sky-high level of debt, the government is playing with fire. In nature, fire melts a snowball. However, in the context of the economic and financial laws of public finances, it stimulates the snowball effect of interest rates.