Is the IMF too upbeat on emerging markets?

A first glance at the IMF’s most recent World Economic Outlook (WEO, April 2020) suggests that emerging markets will fare better than advanced economies during the ongoing crisis and recover faster too. This view may reflect the fact that the crisis is hitting service sectors far harder than manufacturing sectors, and many emerging markets derive a greater portion of their GDP from manufacturing. But the expectation that emerging markets will be more resilient ignores a number of other important factors, including the sudden onslaught of tighter financial conditions for emerging and developing economies and, in many cases, less fiscal space for manoeuvre to deal with the double shock of a health crisis and economic crisis. Indeed, in the IMF’s three alternative (and more pessimistic) scenarios, emerging markets see a dip in GDP growth that is roughly equivalent to that of advanced economies and recover at a slower pace thereafter. This raises the question of why the IMF’s base scenario is so much more positive on emerging markets. Furthermore, given the evolving consensus that the post-coronavirus recovery will take several quarters at least, such a relatively rosy view on emerging markets may soon be tested.

IMF positive on emerging markets

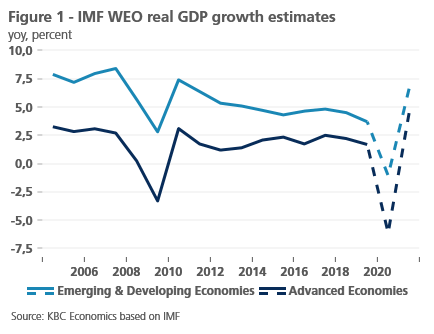

The economic fallout from the coronavirus crisis is

sparing no country. There is, however, debate over whether it is

emerging markets or advanced economies that are better placed to

weather and rebound from the current storm, bearing in mind that

even within emerging markets, wildly different results can be

expected in different countries and regions. Looking back to the

last major crisis, there is some belief that emerging markets fared

better than their advanced economy counterparts. Emerging markets as

a whole did post positive real GDP growth rates in both 2008 and

2009 according to the IMF, while advanced economies saw zero growth

in 2008 and a 3.3% contraction in 2009. However, in relative terms,

both emerging markets and advanced economies saw growth drop by

about 6 percentage points between 2007 and 2009. What’s more,

between 2009 and 2010, emerging market growth recovered less than

advanced economy growth (4.6 percentage points versus 6.4 percentage

points) (figure 1).

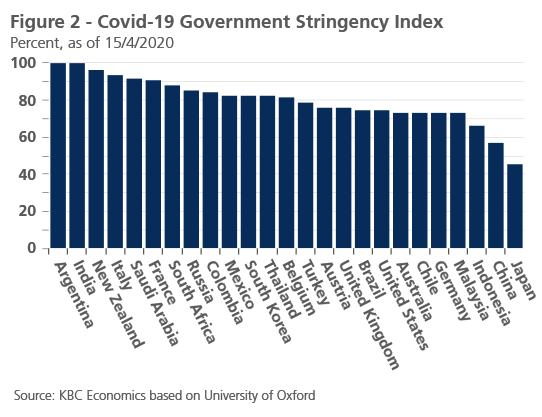

Figure 1 also illustrates the IMF’s latest growth outlook for 2020 and 2021. While both emerging markets and advanced economies are expected to see major hits to growth, the shock to emerging markets is less severe. The only explicitly stated reason in the WEO for this is that as of end-March, many emerging markets were not yet facing the same widespread outbreaks as seen in advanced economies, and therefore had not yet implemented the same severe lockdown measures. However, by mid-April, emerging markets had in mass enacted strict containment measures. According to the Oxford University Stringency Index, of the 15 countries with the strictest measures, only one was an advanced economy (New Zealand). And a comparison of the Stringency Index across several major advanced and emerging economies makes it difficult to say stricter lockdowns have been unique to advanced economies (figure 2).

Another possible reason for the less negative view on emerging markets is the fact the emerging markets are generally less dependent on service sectors and derive a greater share of GDP from manufacturing and external trade. This is an important point, especially as business surveys and preliminary GDP data for Q1 for a number of countries suggest that service sectors are indeed bearing the brunt of the coronavirus crisis. With consumers stuck at home and most non-essential services closed or limited through much of the second quarter, these dynamics make sense. But industrial and external sectors are at risk too, especially as supply chains remain disrupted, and demand will likely take time to recover after the lockdown measures are lifted.

Another important point to keep in mind is that some

emerging markets face higher constraints related to both health care

systems and financing capacities, the latter of which is important

for helping to keep businesses and individuals afloat throughout the

pandemic. Relatedly, financial conditions for emerging markets have

tightened significantly since the beginning of the year, and

throughout March, emerging markets saw massive capital outflows.

While the sudden stop in capital flows has ceased and global

financial conditions have eased thanks to massive central bank

intervention, these issues have not disappeared entirely.

The IMF acknowledges that these factors may lead to a

scenario in which emerging markets face more ‘scaring’ compared to

advanced economies and therefore recover at a slower pace. Indeed,

the IMF lays out three alternative scenarios involving some

combination of (1) the pandemic control measures persisting longer

and (2) the virus returning in 2021. In such scenarios, emerging

markets are expected to see the same initial drop in GDP as advanced

economies despite the concentration in service sectors and precisely

due to “tighter financial conditions and more limited fiscal space.”

Output in emerging markets in the medium term would also remain

further below the baseline in such a scenario as more damage is done

that cannot be addressed by a policy response.

Of course, not all emerging markets can be painted with

the same broad strokes, and there will likely be major regional and

country-specific differences when it comes to handling the pandemic.

For example, emerging Asia appears better situated to deal with and

recover from this shock than Latin America. In general, however,

evolving views on the shape and speed of the recovery suggest that the

IMF’s base scenario may already be too optimistic. Disruptions to

labour markets are severe, businesses have signalled they are likely

to cut back on investment for longer, and it appears consumers may be

unwilling to resume regular levels of spending even if containment

measures are lifted. Emerging markets are facing the same strict

lockdown measures as advanced economies, and global demand will remain

weak as the bounce-back from the coronavirus shock takes longer than

initially anticipated. All this suggests that there are major risks to

the IMF’s relatively more positive baseline view on emerging markets.

Thus, it may take longer for emerging markets to return to their

long-term dynamism.