High number of economically inactive persons in Belgium a cause for concern

Although the jobs motor is running at full tilt, the share of the Belgian working-age population who are in work is very low. The explanation lies not so much in the number of unemployed people, which has fallen sharply in recent years in line with the improving economy, but more in the large and less visible group of other economically inactive people who are (temporarily or permanently) not or no longer looking for work. Bringing these people (back) on board requires a broad approach involving further labour market reforms.

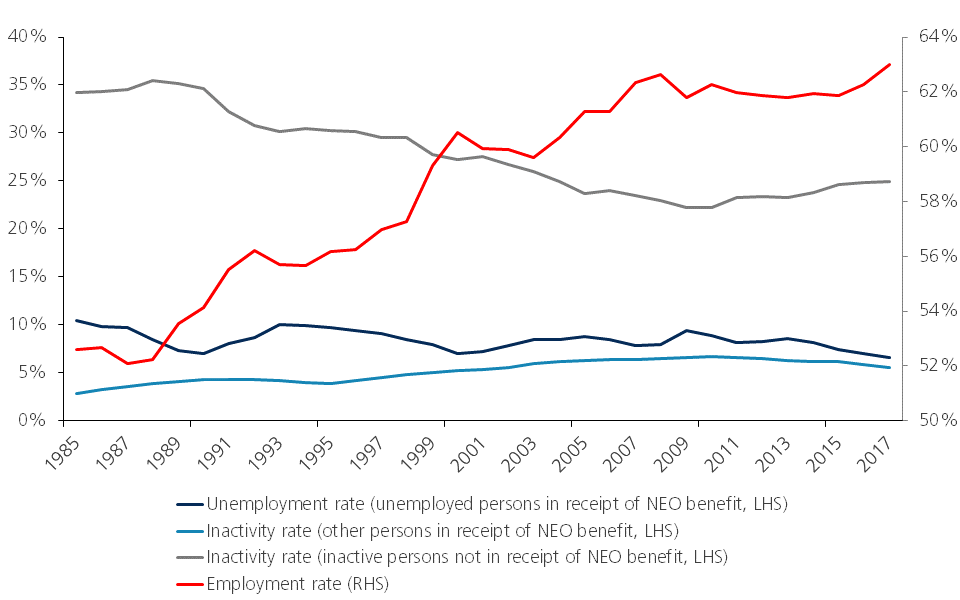

In the previous edition of KBC Economic Opinions on 29 January, it was argued that there are still too many people of working age in Belgium who are not active on the labour market. As a consequence, the employment rate (number of people in work as a percentage of 15-64 year-olds) is low by European standards, though it has increased over the last two years thanks to the improving economy (figure 1). The debate about economic inactivity still often comes down to a debate about unemployment. This includes job-seeking benefit claimants who are fully unemployed as well as those who are temporarily unemployed. The unemployment rate (defined in the figure as a percentage of people aged 15-64 years) has also improved in recent years in line with the better economic climate.

Figure 1 - Acitivity and inactivity in the Belgian labour market (in % of the population aged 15-64 years)

Source: KBC Economic Research based on National Employment Office (NEO) and Stabel (LFS)

However, as well as regular unemployment, there are many other additional forms of inactivity in Belgium, which generally receive less publicity in reports about the labour market. Some members of these additional ‘inactive’ categories receive a benefit from the National Employment Office (NEO) in the same way as unemployed people. These are people who have worked at some time but are not working at present. Some have become unemployed but are no longer required to look for work, for example because of their age (older unemployed persons) or their employment history; they may also be exempt if they are on a company bridging pension or for social/family reasons. There is also a benefit-receiving group who are temporarily unavailable for work for various (sometimes good) reasons, for example because they are on a career break, are using up time credit or are on specific leave (e.g. parental leave).

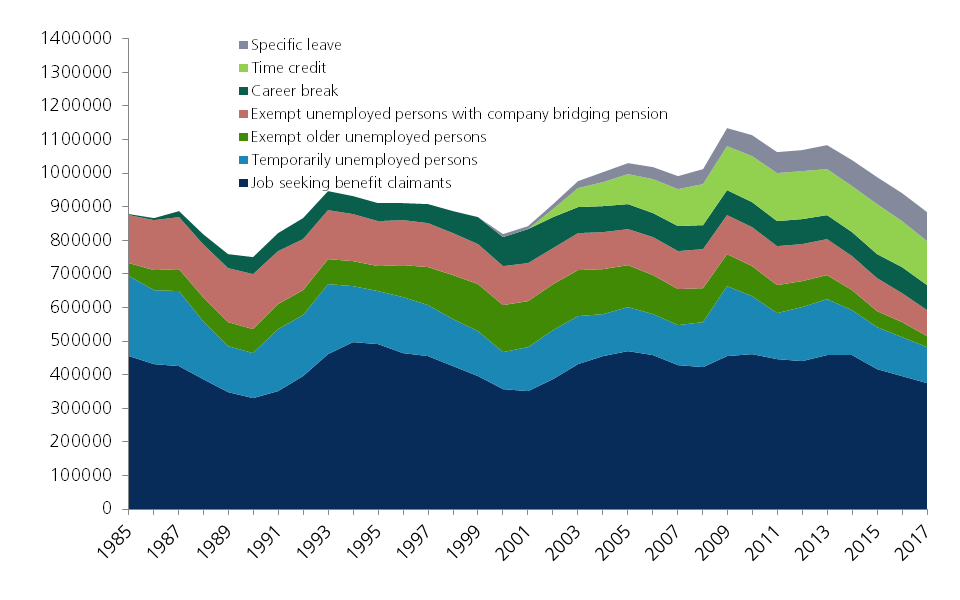

Figure 2 shows the trend in the various economically inactive groups in receipt of a benefit from the NEO. Including the ‘genuine unemployed’, these groups comprised 0.9 million people in 2017, or 12% of the Belgian population aged 15-64 years. It is striking that the number of other people receiving NEO benefits is now almost as high as the number of genuinely unemployed (figure 1). The categories of people on bridging pensions and exempt older unemployed persons, both of which are dying out, have shrunk in recent years, but the other groups remain large.

Figure 2 - Different categories of economically inactive persons with NEO benefit in Belgium (numbers)

Source: KBC Economic Research based on National Employment Office (NEO) and FGS Social Security

Naturally, some of the total inactivity which falls outside the official unemployment figures is unavoidable or even useful (e.g. where people are providing informal care). Nonetheless, there is a group who could in principle (re)join the labour market. The same applies for the even larger group of inactive people who are not in receipt of a benefit from the NEO. Figure 1 shows that after initially declining in recent decades, this group has been growing again since the onset of the financial crisis in 2008. In practice, there can be many different reasons why these people are not or no longer seeking work. Some of them are students, house-husbands and housewives, disabled persons, etc. Economically inactive people not in receipt of NEO benefits accounted for 25% of the population aged 15-64 years in 2017. Some of them were in receipt of a different benefit. For example, the number of people in receipt of social welfare benefit (minimum subsistence allowance) has increased sharply in recent years, and amounted to almost 2% of the population aged 15-64 years in 2017.

If we add together all categories of economically inactive people, we arrive at a figure of 2.7 million Belgians who are not in work (37% of the population aged 15-64 years). And that figure is in fact an underestimate of the actual level of inactivity, because it takes no account of part-time workers or of people who drop out of the employment process due to sickness absence. The long-term absenteeism rate (number of days’ off sick as a proportion of the number of prescribed work days) has risen to a record level of almost 3% in recent years.

All hands on deck

If Belgium wishes to do something about the low activity rate, it will have to fight on all fronts simultaneously. Active integration of unemployed people alone is not enough; more important is to bring other inactive people (back) on board. Clearly, there are people who, for health, family or other reasons, will never (be able to) enter the labour market, and we must understand and respect that. But there are other people for whom such obstacles are less or not relevant. We need those people to help relieve the structural squeeze on the labour market. A mismatch between the jobs on offer and their qualifications must not be allowed to be a major obstacle to their participation; the existing bottleneck occupations cover a wide array of skill profiles which do not always require a specific qualification.

The measures that could be taken are diverse. The most important thing is to make working moreattractive. Working must always pay more than not working. In the first place, this requires a further reduction in labour taxes. The number of people becoming economically inactive also needs to be closely monitored. While the ‘subsidisation’ of this inactivity with social security money is valuable to those concerned, it also comes at a great cost because it leaves labour potential untapped. The amount of government funding spent on ‘passive’ labour market policy (benefits payed by the NEO) as a proportion of the funding for ‘active’ labour market policy (active integration, retraining, etc.) is still among the highest in the EU in Belgium. Attention must also be given to sickness absenteeism. More needs to be invested in the prevention of lifestyle-related conditions, such as burnout, and on promoting labour market re-entry following long-term illness. To make it easier for people to strike a good work-life balance, more scope must be given to approaches such as teleworking. The opportunities for dual learning for young people could also be increased. Many such measures are now being incorporated in labour market policy, but the whole exercise will need to be speeded up over the coming years.