Emerging markets quarterly digest: Q4 2020

Read the publication below or click here to open the PDF.

Recoveries underway with clear differences

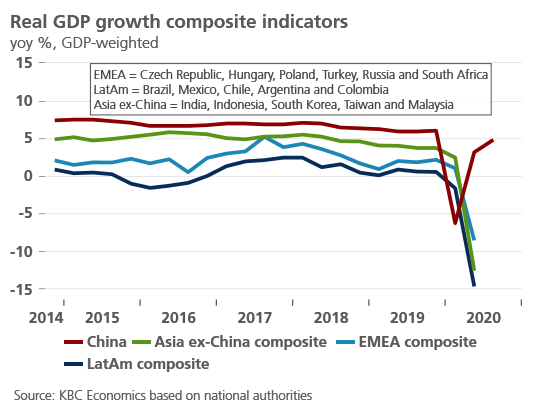

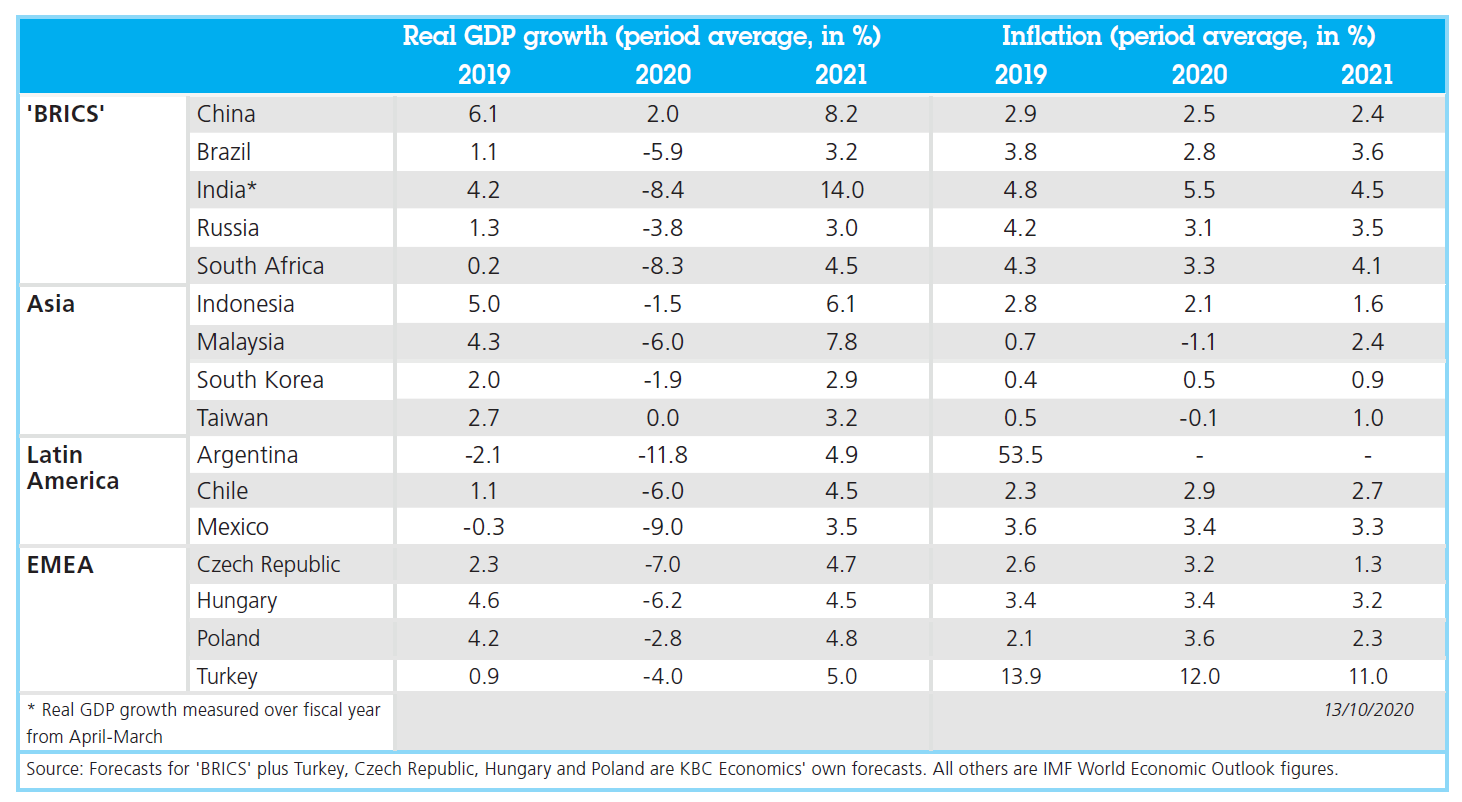

The fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic remains the driving force behind economic developments in both emerging and advanced economies. Though all emerging markets will see a sharp drop in GDP growth in 2020 (with most aside from China registering growth contractions), there are clear differences between emerging markets in terms of the severity of the spread of Covid-19, the magnitude of the hit to economic activity, and the strength and pace of the expected recovery. While some regional tendencies are apparent, even within regions there are clear distinctions. This differentiation also spills over into financial market developments. Easy financial conditions thanks to unprecedented fiscal and monetary support from governments and central banks around the world has underpinned appetite for emerging market assets, but not equally for all economies.

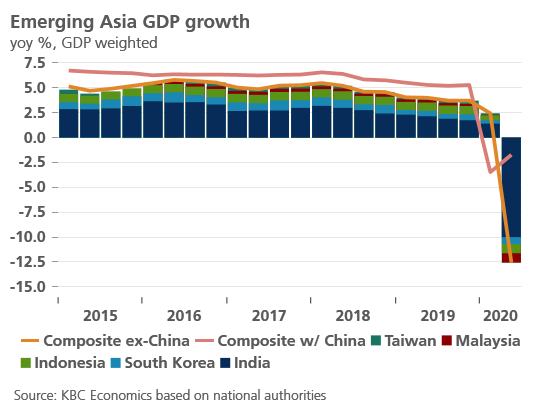

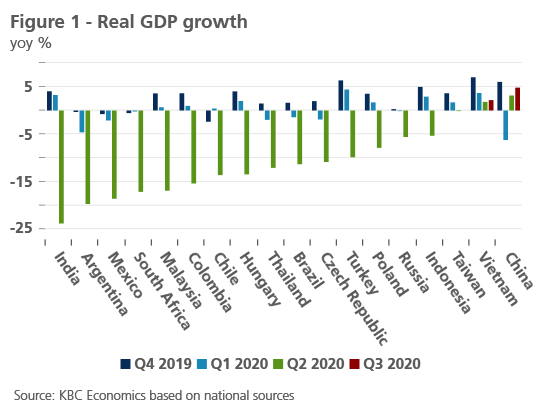

Economic indicators suggest, on the whole, that like the euro area and the US, emerging market economies began or continued to recover in the third quarter of 2020, following sharp contractions in the second quarter due to the spread of the coronavirus pandemic and related lockdowns. The one major exception is China, which remains ahead of the global curve in terms of its recovery trajectory. After contracting 6.8% year-over-year in Q1, the Chinese economy recovered already to postive year-over-year growth in Q2 (3.2%) and continued the recovery in Q3 (4.9% yoy). The pace of the recovery did slow on a quarterly basis, (from 11.7% qoq in Q2 to 2.7% qoq in Q3), but this also reflects a normalization of growth dynamics following the large swings seen in the first half of the year.

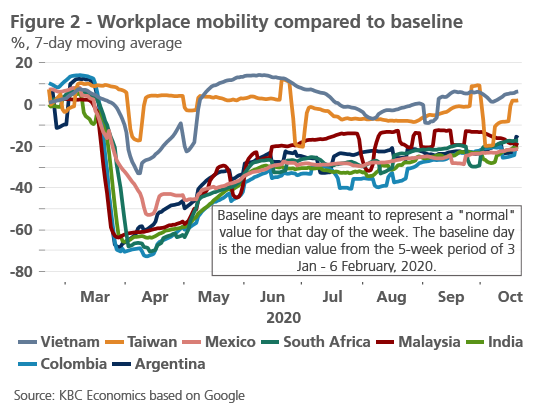

For other economies, the magnitude of the contraction in Q2, and the subsequent recovery in Q3, vary widely. Figure 1 shows real GDP growth rates from Q4 2019 through Q3 2020 (if available) for 18 major emerging markets. For those economies that experienced the most severe contractions, the reasons vary, but India, Argentina, Mexico, South Africa and Malaysia were all facing slowing growth in the quarters leading up to the pandemic outbreak, or in the case of Argentina and Mexico, were already in the midst of a recession. These economies also faced particularly strict lockdowns in the spring, and with the exception of Malaysia, saw a rapid spread of the virus during the second quarter. On the other side, the relatively decent economic performances of Taiwan and Vietnam likely reflect a strong starting position for both economies, good containment of the virus, and the fact that exports held up relatively well in the second quarter, despite the global recession. Furthermore, a comparison of Google mobility data reveals that workplace mobility remained much higher in Taiwan and Vietnam compared to the worst performing economies (Figure 2).

Few economies have released third quarter data as of yet, but higher frequency indicators generally suggest that the recovery is underway in most countries, but again with major distinctions that are not necessarily consistent across regions. On the retail side, for example, Taiwan, Brazil, Turkey and Chile (among others) have returned to pre-pandemic levels, while retail sales in Malaysia, Indonesia, and South Africa are still lagging. On the industrial production side, major economies in Asia appear to have recovered to pre pandemic levels, with the exception of India. Meanwhile, in Latin America, industrial production has recovered from April lows, but remains in negative year-over-year territory for Brazil, Mexico, Colombia and Argentina. For EMEA economies, industrial production is mixed, having rebounded solidly for Turkey and Poland, while remaining in negative territory for the Czech Republic, Russia, and South Africa.

Trade data also generally point to a recovery in the third quarter, with exports and imports bouncing back as economies reopened, but again there are differences. Most major Asian emerging markets saw export growth recover to positive year-over-year territory in September (with the exception of Indonesia and Malaysia, the latter of which has not yet released September trade data). To some extent this reflects the recovery in China, but for economies like Taiwan and Veitnam, it also reflects continued demand for high-tech products. In Latin America and emerging EMEA (Europe, the Middle East and Africa), the export picture is somewhat weaker, especially for commodity-dependent exporters like Colombia and Russia.

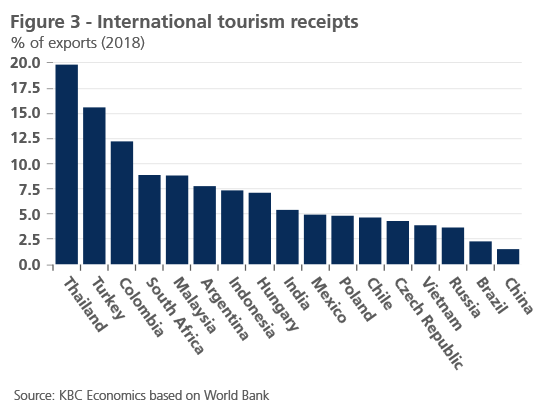

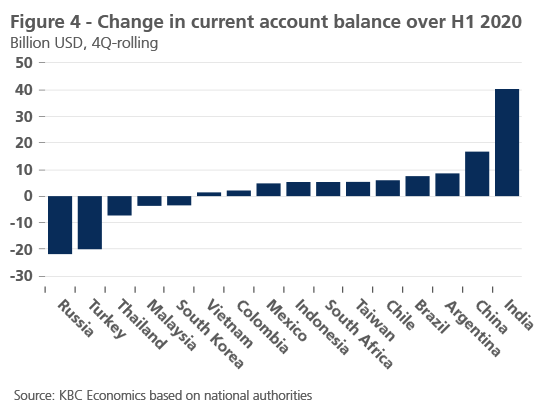

In general, the pace of the recovery going forward will depend on several factors, including the relative containment of the virus in each economy, the recovery in important trading partners, and the importance of sectors that continue to be highly impacted by the pandemic, such as hospitality and tourism. As Figure 3 highlights, international tourism receipts as a percent of exports in 2018 were highest for Thailand, Turkey, Colombia, South Africa and Malaysia. It is perhaps not surprising then, that Thailand, Turkey and Malaysia saw some of the largest drops in their current account balances (on a 4-quarter rolling basis) over the first half of 2020 (Figure 4).

Other structural factors may also impact the extent to which the pandemic causes damage to each economy’s potential growth. As mentioned in a previous edition of this digest, countries with a high percentage of the population below the national poverty line (such as South Africa, Mexico, Argentina, Colombia or Brazil), or that have a high share of workers in the informal sector (such as India, Indonesia, Colombia and Brazil) may see inequality widen, which will weigh on the longer-term recovery. Finally, while governments around the world have delivered unprecedented policy support to combat the virus and its economic effects, some emerging markets have more limited space to maneuver in terms of both their fiscal and monetary policies. For now, however, the general easy financial conditions globally are supporting emerging market assets—but not evenly (See Box: Easy financial conditions mask emerging market financing and sustainability risks).

Box: Easy financial conditions mask emerging market financing and sustainability risks

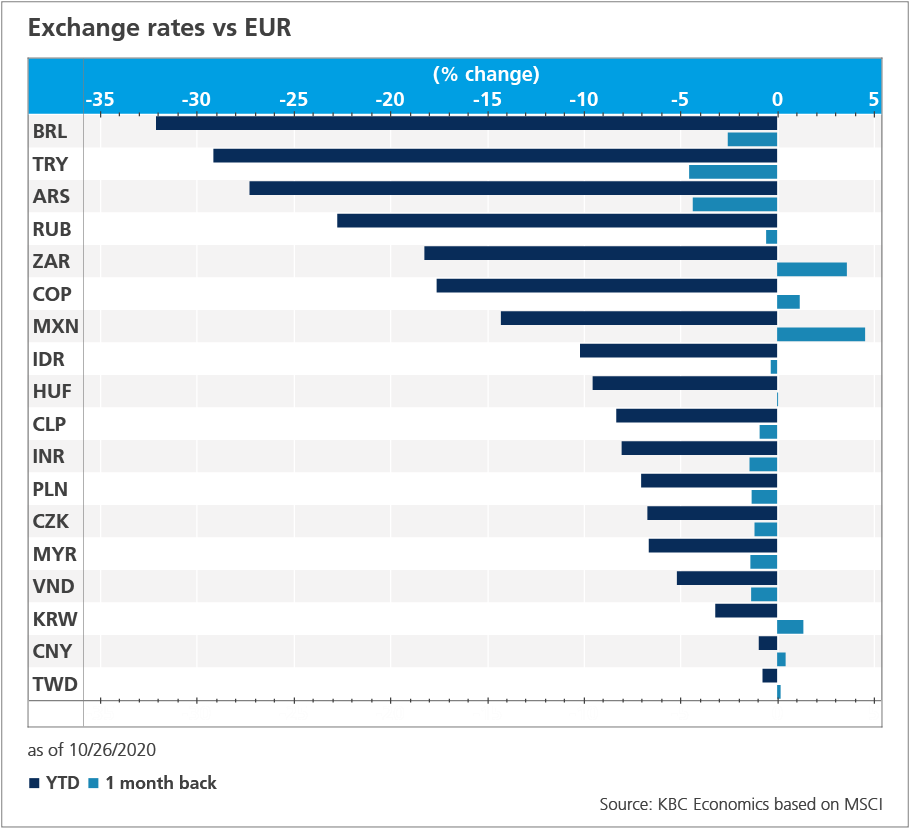

Despite the massive economic destruction caused by the coronavirus pandemic, the financial system has so far weathered the crisis with few major disruptions. An important reason for this is the massive stimulus that has been pumped into the global economy, especially by monetary authorities. Easier global financial conditions have clearly benefited emerging market assets. Following sharp depreciations at the beginning of the year, most emerging market currencies have partially rebounded versus the USD since end-March (the Brazilian real, Turkish lira, and Argentine peso are the exceptions). Portfolio flows have also recovered after the dramatic outflows witnessed in the Spring albeit at a relatively slow pace.

The financing situation for many emerging markets, however, remains no walk in the park. As the IMF explains in its October 2020 Global Financial Stability Report, local currency issuance for some economies has picked up, enabling them to cover much of their higher projected deficits. Other emerging markets, however, have had to delay their local currency debt issuances or are relying more on foreign currency issuances. Indeed, according to the IMF, most of the recovery in emerging market portfolio flows has been driven by foreign currency issuance.

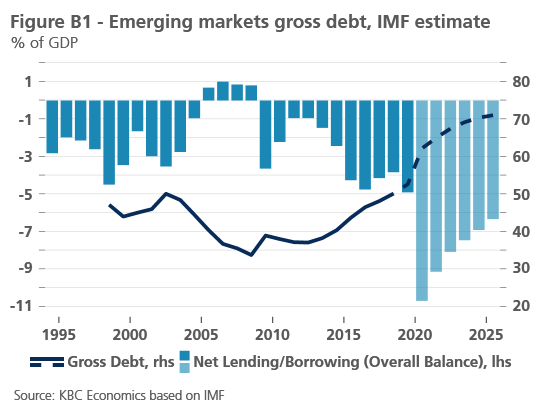

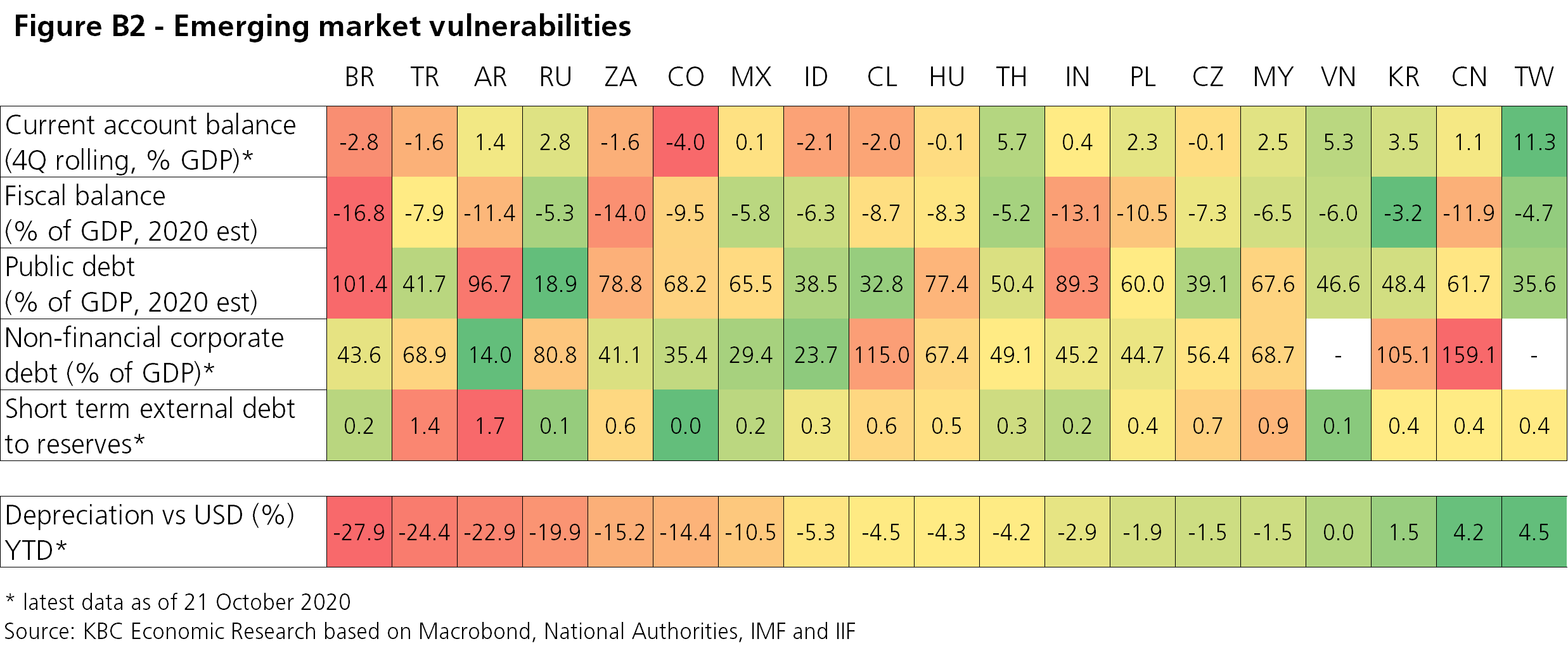

Overall, this suggests that emerging market vulnerabilities are rising. Due to higher spending in an effort to cushion the blow of the pandemic, lower tax revenues, and sharply lower GDP levels in most countries, emerging market sovereign debt ratios are expected to jump significantly this year. The IMF estimates gross emerging market debt will rise to 62% of GDP in 2020 (Figure B.1). Where more of this debt is held in foreign currency, external vulnerabilities become even higher.

Among the major emerging markets, 2020 fiscal deficits are expected to be particularly high for Brazil, South Africa, India, and China (Figure B.2). However, it is not only the major emerging markets that face high financing needs. A number of low-income economies have benefited from the G20 debt service moratorium and support from the IMF and World Bank this year. But there have recently been renewed calls for more international action to support low-income economies as they attempt to tackle the health and economic crisis brought on by the pandemic. Support for low-income economies is more than a moral imperative though. The global financial landscape is relatively calm despite the tenuous economic situation. A wave of debt crises in low income economies could disrupt that calm, adding further uncertainty to the outlook for the global recovery.

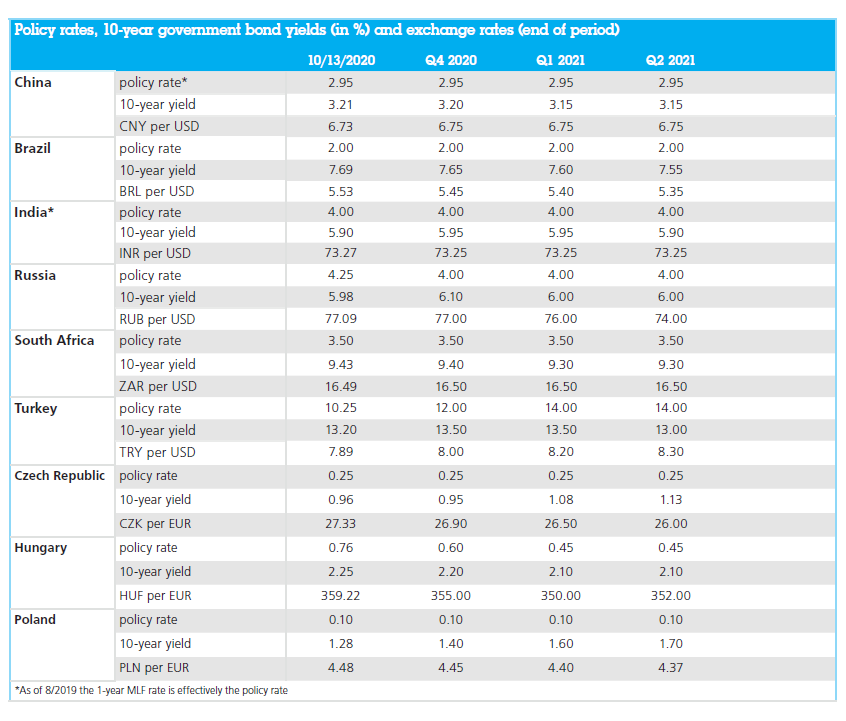

On the currency front, we see that many emerging market currencies have partially recovered after depreciating sharply versus the USD at the beginning of the year. The Brazilian real, Turkish lira, and Argentine peso are the exception, and their underperformance is not particularly surprising given long-standing structural issues and external vulnerabilities in these economies. On the other side, we see that several Asian currencies have outperformed, reflecting a generally brighter growth outlook for that region and more limited external vulnerabilities.

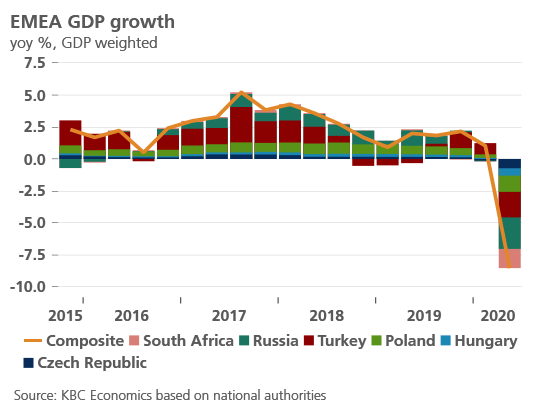

Central and Eastern European currencies have been more in the middle of the pack. The clear underperformer within the region has been the Hungarian forint, having lost more than 10% compared to its 2019 average, which prompted the Hungarian central bank to react by unexpectedly hiking the interest rate on its one week facility by 15 basis points to 0.75% at the end of September. Meanwhile, currency weakness was a somewhat lesser issue for the Polish zloty and the Czech koruna, both having lost roughly 4%.

Why? First, Hungarian economic fundamentals have deteriorated more significantly than those in Poland and the Czech Republic. Compared to the 2019 average, Hungarian GDP fell by roughly 14%, while Czech GDP fell only 11% and Polish GDP roughly 8.5%. Also, despite the significant drop in GDP, the Hungarian current account balance deteriorated over the course of 2020 from a minor surplus to a deficit of roughly 1% of GDP. Meanwhile, the Polish current account balance improved significantly and that of the Czech Republic remained more or less flat. The combination of a deeper contraction and growing external imbalances clearly poses higher risks for Hungarian assets.

Virus uncertainty reigns

Despite the ongoing economic recovery, the pandemic is far from over and remains a key uncertainty for every country going forward. In general, we see that a number of East Asian and Southeast Asian countries continue to keep the pandemic well under control compared to others. In China, Thailand, Vietnam and Taiwan, daily case rates remain relatively low (below 0.01 cases per 100,000 people). Daily Case rates per capita were higher but are now starting to stabilize in India, Indonesia, Colombia, Chile, Brazil, Mexico and South Africa. In contrast, several Central and Eastern European economies (including the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Russia), are seeing a sharp rise in the number of confirmed cases and have surpassed the levels registered during the ‘first wave’ in the spring. Rising case rates, especially in countries where governments have introduced new restrictions to fight the spread of the virus, may hinder the pace of the economic recovery in the fourth quarter.

Emerging Asia

China leads the recovery

China continues its strong recovery, with the economy growing 4.9% yoy in the third quarter. This puts China on track to reach 2.0% annual growth in 2020, making it the only major economy expected to record positive growth this year. So far, China’s recovery has reflected a ‘two-speed’ economy, with higher investment boosting the industrial sector, while consumption and the retail side of the economy lagged behind. The most recent GDP figures, as well as high frequency data on retail sales (3.3% yoy in September), however, suggest that consumer demand in the Chinese economy is indeed recovering. For example, while final consumption contributed negatively to year-over-year GDP growth in Q2, it contributed a positive 1.7 percentage points in Q3. Investment still leads the way, however, contributing 2.6 percentage points to third quarter GDP growth.

The relative strength of investment and the industrial sector partly reflects the Chinese authorities’ approach to stimulus, which entails relying on State-Owned Enterprises and local governments to boost infrastructure and investment. While this approach has clearly helped orchestrate a swift recovery following the steep collapse of economic activity in the first quarter, it is not without risks. In particular, already highly indebted local governments and SOES are seeing their debt ratios rise even further (see KBC Economic Opinion: China’s investment-led growth is a double-edged sword for further analysis). Despite these risks, given strong data of late and the fact that the pandemic there remains mostly under control, we have revised up Chinese GDP growth to 2.0% in 2020 and 8.2% in 2021.

India’s devastating second quarter

India, meanwhile, suffered the largest collapse in real GDP in the second quarter compared to emerging market peers (-23% yoy). While all components fell sharply compared to the first quarter, the particularly dismal growth figure was due to a major collapse in private consumption (contributing -12.99 percentage points). As mentioned above, India also faced a particularly strict lockdown which greatly hindered mobility and likely contributed to the sharp fall in consumption. On the positive side, however, the recovery in India does look to be underway. India’s sentiment indicator for the manufacturing sector, for example, recovered to 51.6 in September, indicating expansion. Reflecting trends seen elsewhere, services sentiment remains weaker (41.9 in September) but has improved significantly compared to lows reached in June. Passenger vehicle sales have also recovered, growing 24.9% yoy in September, after contracting a massive -89.9% yoy in May, suggesting that domestic consumption is on the rebound. Daily Covid-19 case numbers have also started to stabilize, which will hopefully provide space for the recovery to take hold. The recovery is not yet on fully solid footing, however. Industrial production has not completely recovered (reaching only -8% yoy growth in August). Furthermore, while consumer confidence surveys suggest that views on the future outlook have improved, views on the current outlook declined further in September. Overall, given the dismal Q2 growth figure, we have downgraded Indian GDP growth to -8.4% for FY 2020. In FY 2021, however, we expect a strong (albeit somewhat mechanical) recovery with annual growth at 14%.

Latin America

In Latin America, after seeing a constant rise in daily Covid-19 case rates over the summer months, the numbers appear to be stabilizing in the largest economies. The one exception is Argentina where daily new cases are still on the rise. A relative reprieve from the spread of the virus would be welcome news for the region, where many countries were facing slowing growth or were recovering from a recession before the pandemic hit. All major economies in the region subsequently saw sharp contractions in second quarter GDP growth, with Argentina suffering the most (-19.77% yoy) and Brazil contracting the least (-11.4% yoy). Argentina, of course, has been juggling more than just the coronavirus crisis. For the past several months the country has been locked in negotiations with creditors over restructuring its debt. A deal was finally secured in September, which will allow the country to avoid another default.

A recovery in the region does appear to be underway, but the strength of that recovery varies. Retail sales have fully rebounded in Brazil and Chile, for example, but remain weak in Mexico and Colombia. Industrial production figures tell a similar story. However, even for Brazil, though the economy clearly started to recover in the third quarter, that recovery may be somewhat sluggish. A monthly GDP tracker for Brazil suggest that on a rolling 3-month basis, GDP was still down -0.7% compared to a year earlier. Overall, we expect Brazil’s economy to shrink by -5.9% this year before recovering 3.2% in 2021.

EMEA

Central and Eastern Europe sees virus surge

Following the unprecedented economic contraction in the second quarter, recent high frequency indicators suggest that the recovery in Central and Eastern European economies progressed further over the summer months. Nonetheless, uncertainty surrounding the pace and strength of the recovery remains substantial, in particular due to the resurgence of the Covid-19 virus across the region.

While in March and April national lockdowns helped contain the virus and the region was praised as a role model, it is now among the hardest hit in the EU. All countries have seen an upward trend in the number of new cases with an exceptionally strong second wave in the Czech Republic. This is particularly interesting as the country went from an impressive success story in the spring to a quick reversal, now recording the highest number of new cases per 100,000 inhabitants in the EU.

The adverse epidemic developments have already triggered some tightening of containment measures across the region, though they are not as stringent as during the first wave. This should, in our view, limit the economic damage compared to March and April, but some headwinds to economic activity are likely. We think it is still too early to estimate the ultimate impact of the restrictive measures as we see important changes to the measures almost daily. Hence, while we currently maintain our regional growth outlook unchanged, some update might be warranted soon.

Russia still has policy space to work with

The Russian economy contracted by 8.1% yoy in the second quarter, slightly less than expected. Together with still positive year-on-year growth in the first quarter, the economy fell by a relatively modest 4.3% in H1 2020, outperforming most of the regional peers. This is largely due to the specific structure of the Russian economy, i.e. being less vulnerable to the covid-type of a shock. Indeed, ‘social consumption’ sectors such as restaurants, entertainment or tourism play a smaller role in the Russian economy compared to peer countries.

Available high frequency indicators suggest that strong recovery was underway in the third quarter. Both the services and production sides of the economy have rebounded quickly after the reopening, though the level remains below the pre-pandemic period in both cases. Sentiment indicators, namely the PMIs, however, indicate some softening in activity heading to year-end, with manufacturing index dropping below the 50-level marking the contraction territory.

At the same time, the second wave of the pandemic has been spreading fast with new daily cases surging to a record of 16,000 (keeping in mind that more robust testing capacity is now in place). This will likely hinder the rebound in economic activity. An offsetting factor might appear if a vaccine for the mass population is available by the end of the year as the government has envisaged. Overall, we expect the Russian economy to contract by 3.8% this year, followed by growth of 3.0% in 2021. Still, uncertainty surrounding our outlook remains high, particularly related to the Covid-19 trajectory.

Should the renewed outbreak of the Covid-19 result in strong headwinds to the economy, both fiscal and monetary policy have available space to accommodate the negative shock. As for now, the government has announced a return to a more prudent fiscal policy meaning that stimulus is set to moderate. Meanwhile, the central bank is now in ‘wait and see’ mode, particularly due to the heightened FX volatility and elevated geopolitical risks, such as US presidential elections and the possibility of renewed sanctions or disputed presidential elections in Belarus. Nonetheless, with disinflationary pressures being more prominent, we expect an additional 25 bps cut by year-end, bringing the benchmark rate to 4.00%.

Turkey

The Turkish economy plunged by 11% qoq in the second quarter with a broad-based decline across the demand components. While this marks the worst quarter-on-quarter contraction on record, it was not as bad as many feared and Turkey outperformed many of its emerging markets peers. Furthermore, the recent high frequency indicators all suggest that a rapid economic recovery was underway in the third quarter. This looks surprising given the fact that Turkey entered the coronavirus crisis as one of the most vulnerable economies, following a fragile recovery path since the 2018 currency crisis.

The surge in economic activity has been heavily supported by a massive state-backed credit boom with TRY lending growth having increased from 15% yoy in March to almost 40% yoy in September. As such, the authorities have chosen to prioritize growth over containing macroeconomic imbalances - a similar response to the past slowdown. The flip side of the rapid credit expansion has been a large current account deficit, as well as a sharp lira weakening (for more analysis on Turkey see KBC Opinion: Turkey beats peers but faces higher risks).

South Africa

South Africa saw one of the sharpest drops in second quarter GDP growth compared to emerging market peers with a contraction of 17.2% yoy. After peaking in July, however, South Africa appears to have brought the spread of the coronavirus partially under control, at least for the time being. In line with this, economic indicators suggest that the recovery in South Africa is underway but may be sluggish. Manufacturing production has improved from its April low (-48% yoy) but still remains weak at -9% yoy in August. Mining production, meanwhile, has improved somewhat more, to -1% yoy in August. The South African Reserve Bank’s leading indicator series shows a similar story (-0.5% yoy in August, compared to a low of -10% yoy in April). Despite this shaky recovery, fiscal space for further stimulus remains limited without worsening already stretched macroeconomic imbalances. The IMF, for example, foresees a budget deficit of 14% of GDP in 2020 and public debt at a relatively high 78.8% of GDP. Overall we expect South Africa’s economy to contract -8.3% in 2020 before recovering 4.5% in 2021.

Tables and Figures