Economy versus public health: a false contradiction

Link to the pdf

Despite all the good intentions, the (Western) world did not prevent a second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic. The misleading nature of the exponential growth of the virus plays a role in this. Exponential growth will eventually lead to a gigantic increase, but in the beginning, it is hardly noticeable or alarming. Measures to slow the spread of the virus are postponed because of their socio-economic cost. However, there is no fundamental contradiction between public health and the economy. Without public health, no thriving economy is possible. Rapid and decisive action to nip a flare-up of the epidemic in the bud, together with measures to safeguard economic continuity, are therefore essential. Mutatis mutandis, lessons can be drawn from the bold way in which the US and German central banks reduced inflation after the second oil shock in the 1970s and German unification respectively. After all, inflation is also an exponential phenomenon.

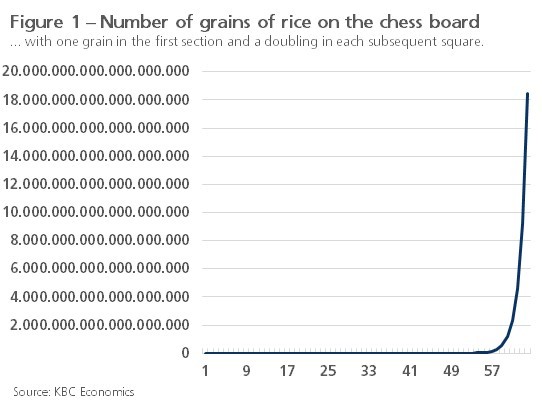

18 trillion rice grains

The (Western) world is struggling to control the Covid-19 pandemic. There are many reasons why, despite all good intentions, a second wave of infections has not been prevented. The way in which the virus is transmitted, for example, is the subject of advancing insight.

However, it is clear that the transmission follows an exponential curve. Anti-coronavirus policies can make use of this insight. Unfortunately, this does not appear to be so simple in practice. This has to do with the misleading nature of exponential growth. In the long run, it will result in a gigantic increase. At first, however, it hardly attracts attention or does not raise the alarm. As a result, the result surprises, although it was fairly predictable.

The story of the inventor of the chessboard makes this clear. When the inventor presented his invention to the king centuries ago, according to the story, the king was so enthusiastic that he allowed the inventor to determine his own reward. It had to remain a 'reasonable' reward. The inventor proposed to be paid in grains of rice. The number would be determined as follows: one grain for the first square of the chessboard, two grains for the second square, four for the third, eight for the fourth, and so on. Each subsequent square would yield twice as much as the previous one.

Initially, the king laughed at the inventor. The king thought that the inventor was taking too low a reward. He did not realise that he would have to pay more than 18 trillion grains of rice (figure 1). That is a billion times more than 18 billion grains of rice, a mountain of rice that would make Mount Everest pale and a multiple of the world production at that time.

The king was fooled by the misleading nature of exponential growth. With the doubling at each subsequent square of the chessboard, there are still only 255 grains of rice on the board at the end of the first row. Filling the second row increases that number to just over 65,000. That is a lot, but still an understandable number. Halfway down the plate, the number has risen to 4.3 billion grains of rice. That already seems enormous, but it is hardly noticeable on a graph (figure 1). After all, it sinks into nothingness compared to the amount of rice that the further doubling on the second half of the plate yields.

Predictable surprises

Viruses spread exponentially and are therefore 'predictably surprising'. As long as there is no adequate medical defence against the virus that causes Covid-19, its exponential spread must be slowed down mainly by restricting human contacts. From an epidemiological perspective, it seems fairly clear that drastic lockdown measures are most effective in this respect. But they clash with personal freedom and have a high socio-economic cost. As a result, there is great resistance to strict measures, at least as long as the figures do not alarm.

However, overly flexible measures leave the virus free rein. This is where the misleading nature of exponential growth comes into play. In the initial phase of the increase, the number of infections remains limited. It is insufficiently alarming and does not create a basis for limiting social contacts. Consequently, the virus can 'quietly' spread further.

As long as not too much virus circulates, testing, contact tracing and selective quarantine are relatively soft measures to control the spread. But this approach is not (yet) available without capacity limits. With increasing infections, they run up against capacity limits. This breaks an important defensive dam against the epidemic. The alarm bells only really go off, however, when the medical system threatens to collapse under the number of coronavirus patients.

Is there a choice?

The choice of the appropriate severity of measures in the anti-coronavirus strategy is sometimes seen as the search for a balance between three objectives: (1) safeguarding personal freedom, (2) limiting the socio-economic cost of the measures and (3) preventing an overload of the medical apparatus. Others point to the irreconcilability of the three objectives. As in the management triangle, one objective must then be subordinated to the other two, and the policy must consistently respect that choice. Preventing an overload of the medical apparatus requires a restriction of individual freedom or the acceptance of a higher socio-economic cost. If an absolute choice is made to safeguard personal freedom and no socio-economic cost is tolerated, a high health toll will inevitably follow.

The question can, however, be asked whether the exponential dynamics of the virus leave any room for sensible choices. Consider, for example, the trade-off between measures to curb the spread of the virus and the avoidance of socio-economic costs. If people fall ill or become infected due to a lack of measures, schools and companies cannot run at full capacity. The pandemic therefore creates socio-economic costs even without these measures. The more sick and infected people there are, the higher the costs. Measures to counter infections do create immediate socio-economic costs, but they also help to prevent them in the long term.

Research on the first wave also showed that the immediate economic cost of the pandemic is not only caused by the lockdown measures as such, but also by the dynamics of the virus itself. In the event of a resurgence of the virus, people voluntarily restrict their mobility and, consequently, their purchasing behaviour, regardless of the prevention measures taken (see KBC Economic Research report of 17 September 2020).

The second wave in Belgium seems to confirm this. In October, according to Google's mobility data, it led to a decrease in mobility for retail and recreation before the lockdown took effect (figure 2). Surveys by the Economic Risk Management Group pointed to a stagnation in economic recovery and a sharp increase in absenteeism as a factor hampering production already in the second half of October. Conversely, the rigorous and vigorous response to the flare-up of the virus in Antwerp at the end of July did not prevent the economy from growing surprisingly strongly in the third quarter of 2020.

Therefore, the choice between taking measures to contain the virus and avoiding socio-economic costs seems to be false to a certain extent. Let us leave aside here the scope for personal freedom that is possible when a pandemic has got out of hand and there is a risk of infection behind every corner.

There is no thriving economy without public health. As long as there is no adequate medical defence against the virus, measures to control its spread therefore also support the economy. The exponential nature of the spread of the virus requires these measures to be taken quickly and decisively. As with any government intervention, these measures must be efficient and effective. The socio-economic cost may then be relatively limited, if they are accompanied by compensatory measures to safeguard economic continuity. However, delaying for fear of the immediate cost threatens to increase the later cost.

Learning from monetary policy?

Two historical examples of the fight against inflation could perhaps be enlightening in this context. Inflation is also exponential. It measures the (annual) rise in the general level of prices in an economy. This rise must be kept limited and stable. Otherwise, out-of-control inflation threatens to disrupt the economy, as seen in post-war Germany. That is why in many countries, the pursuit of not too high, stable inflation is (one of) the most important objective(s) of the central bank.

The current deflationary environment may have blurred the memory, but there have been periods in which slowing a rise in inflation has provoked drastic intervention by the central bank. When the second oil shock in the late 1970s raised US inflation from 5% in late 1976 to almost 15% in spring 1980, the US central bank quadrupled its policy interest rate to 20%. More than ten years later, after German unification, the economic boom drove German inflation to almost 5%, more than double the Bundesbank's target. Promptly, it raised its policy rate drastically to almost 10%.

In both cases, this drastic adjustment of monetary policy had a serious cost. Both in the US and ten years later in Germany, the economy tumbled into a deep recession with high unemployment. Moreover, the German rate hike plunged the then European system of exchange rate agreements (the EMS) into an existential crisis, only a few months after the signing of the Maastricht Treaty that paved the way for the European currency union.

In both cases, the decision-makers were convinced that the short-term economic cost of the decision outweighed the damage that could be expected in the long term if the decision was not taken. The policy had both supporters and opponents. Meanwhile, history has shown that the dreaded derailment of inflation did not happen. The long-term cost has therefore been avoided. Whether this could have been done at a lower cost in the short term cannot be established with certainty. It is the fate of economists that they do not have a laboratory for assessing what the world would look like under alternative policy decisions.

Any comparison is a little flawed. In the historical examples, the culprit was an economic problem. In the current crisis, the culprit comes from outside the economy. Mutatis mutandis, the examples do show that if the culprit threatens to cause damage in an exponential way, it may be worth accepting a short-term socio-economic cost. The contradiction between economy and public health then becomes false. Because the culprit now comes from outside the economy, it is advisable to limit the socio-economic damage of the fight against it as much as possible with an accompanying policy aimed at economic continuity.