Economics and sustainability clash on the Nile

Over the past decade, no economy has dazzled quite like that of Ethiopia. With an average annual growth rate of 9.5% for 2009-2019, according to the IMF, Ethiopia had the fastest growing economy in the world. While this in part reflects the fact that Ethiopia is a relatively poor country, with room to grow before reaching even middle-income status, a significant part of the country’s economic success can be attributed to a state-led infrastructure boom. One major infrastructure project has been the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam, which is a 2-kilometre-long hydroelectric power plant on the Blue Nile that will have the capacity to produce over 6,000 megawatts of electricity, make Ethiopia a major electricity exporter, and propel the country towards middle income status. With 11 years and USD 4.6 billion sunk into the project, a substantial part of which was financed locally, the dam is an important symbol for Ethiopia’s economic future. But Egypt too relies economically on the Nile, sourcing 90% of its freshwater from the river, especially for agriculture. The two nations are therefore embroiled in a bitter conflict over how the dam will be filled and managed. In the context of climate change, this conflict illustrates two important points; economic growth considerations cannot be compartmentalized from sustainability issues, and climate change is a global phenomenon that requires international cooperation to avoid major conflicts.

Ethiopia’s massive success

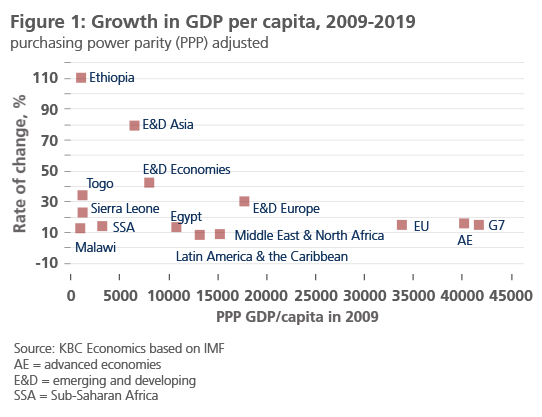

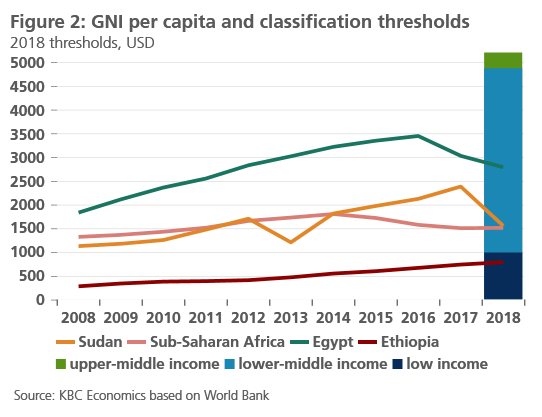

Ethiopia’s economic development over the past ten years has no doubt been impressive. It grew faster than any other economy in the world as its real GDP level more than doubled between 2009 and 2019. And though Ethiopia started at a lower base compared to many other countries (in terms of income), its growth performance was also far stronger than that of peer countries who started the last decade with similar GDP per capita levels (figure 1). Despite this fast growth, however, Ethiopia is still a low-income economy, with a GNI per capita level that is below that of both Egypt and Sudan, the two countries downriver from the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) (figure 2). Furthermore, the state-led, investment-focused growth policy of the last ten years has left Ethiopia with growing imbalances (e.g. a growing public debt burden, a high current account deficit and sparse foreign exchange reserves).

The government under Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who won the Nobel Peace Prize for his peace-making efforts with regards to the Eritrea border conflict, however, has a plan to address these imbalances and to continue driving the country towards middle-income status. The main initiatives of this plan are to privatize certain industries and open up some sectors to competition and foreign investment while also tightening monetary policy and shoring up the fiscal balance. The government’s plan also involves leveraging the new infrastructure amassed in recent years. With such reforms, Ethiopia has become the darling of institutions like the IMF and World Bank, securing funding assistance of USD 3 billion and USD 1.2 billion from each institution respectively.

A controversial project

One of Ethiopia’s more notable infrastructure projects has been the construction of a massive hydroelectric dam on the Blue Nile. The project has taken almost a decade to complete and cost USD 4.6 billion, which is equivalent to roughly 6% of Ethiopia’s annual GDP. Estimates suggest the dam will quadruple Ethiopia’s electricity production capacity. This will improve access to electricity in Ethiopia, which stands at only 44% of the population versus 86% on average for lower-middle income countries, help the manufacturing sector, which is constrained by power outages and difficulties accessing electricity, and help make Ethiopia an electricity exporter. It is therefore not surprising that Ethiopia wants to fill the dam’s reservoir as quickly as possible.

But Ethiopia is not the only country with economic claims to the Nile. 90% of Egypt’s fresh water comes from the Nile and the country is understandably concerned about water shortages that might be created by the GERD, especially in the context of climate change and the possibility of long droughts. Sudan also relies on the Nile, but it is now less opposed to the GERD than it once was given the benefits it might accrue in terms of cheaper electricity and protection from destructive flooding.

A warning, and perhaps inspiration, for the future

The hope is, of course, that these nations will come together and decide on a plan that allows all countries to grow and prosper economically without threatening any other nation’s water or electricity supply. In recent weeks the US Treasury and the World Bank have acted as intermediaries to try and arrive at an agreement that will avoid an escalation of the conflict. Ministers from the concerned nations will meet again in Washington D.C. this week to hopefully decide on a comprehensive and final agreement.

However, the conflict also illustrates a larger issue that flows well beyond the banks of the Nile. In a world where extreme weather is projected to become more common and costly, where shortages of clean water and other natural resources are expected to become more severe, and where there may be disparities between a country’s income level and what it should be expected to do to limit carbon emissions, economic concerns and sustainability concerns are inextricably intertwined. Indeed, investment in water infrastructure is becoming increasingly important in the context of climate change. What’s more, countries with perhaps countervailing interests regarding sustainability will have to cooperate more on these issues to avoid conflicts. With Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan reportedly close to finding a compromise on an extremely sensitive issue for all parties involved, this dispute will hopefully serve as not only a warning of the types of conflicts we may see more of in the future, but also as an example of how countries can work together to overcome such challenges.