Deglobalisation slows the decline in global inequality

Over the last three decades, global income inequality showed a substantial decline. The improvement reflects the balance of two opposing trends, i.e. a drop in inequality between countries and a rise in inequality within countries. Despite what people often think, the process of globalisation has had a positive impact on decreasing global inequality by fostering GDP-per capita convergence between emerging and advanced countries. Nevertheless, it may also have contributed to increasing within-country inequalities. In more recent years, we saw a stabilisation, and in some cases reversal, in within-country inequalities. Aside from country-specific factors and policies, this may be linked to ongoing trade protectionism and deglobalisation. The latter trend however also reduces the speed of the income convergence between emerging and advanced economies. This causes a slower reduction in inequality between countries and for the world as a whole.

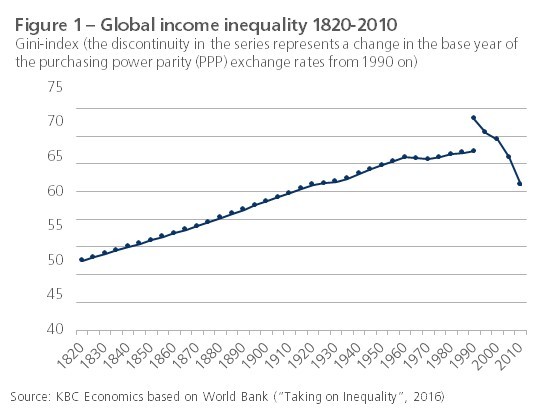

The recent decade brought increasing attention to the problem of inequality. This was in part triggered by the success of Thomas Piketty’s book (“Capital in the Twenty-First Century”, 2014) and by World Bank inequality statistics, which pointed to increasing income inequality within many individual countries. Despite some recent improvement, average within-country inequality is greater now than a number of decades ago, with the increase being particularly visible in the US and other Anglo-Saxon countries. This view, however, disregards a substantial narrowing of income inequality at the global level since the 1990s, i.e. inequalities between individuals in the entire world disregarding national borders. The decline is the first structural reduction since the industrial revolution (figure 1). From 1820 till the 1990s, global inequality steadily rose.

The role of globalisation

The sharp drop in global inequality occurred during a period of increasing global economic integration, the so-called process of globalisation. Countries’ GDP-per capita levels (measured in purchasing power parity terms) converged as (often populous) lower-income countries, such as China and India, grew much faster than higher-income countries. In contrast, demographic changes (i.e. stronger population dynamics in the lower-income countries) and increasing within-country inequalities reduced the effect of GDP-per-capita convergence and therefore put a brake on the declining trend in global inequality.

A variety of factors may explain the rise in inequality within countries. In emerging economies, the increase often is a temporary phenomenon associated with the early stages of development. Once the benefits from economic development become more broadly shared and a welfare state takes hold, inequality declines. In the literature, this relationship between economic development and inequality is known as Kuznets’ inverted U-curve. In more advanced economies, factors that have driven higher income inequality are more complex. They include, amongst other things, shifts toward less progressive fiscal regimes (especially in Anglo-Saxon countries), technological progress (favouring capital and skilled labour over low-skilled labour) and the ineffectiveness of education, labour market and social policies in tackling poverty and promoting more inclusive growth.

The globalisation process, which helped to reduce the income gap between lower- and higher-income countries, may also have contributed to increasing national inequalities, especially in advanced countries. There are various channels through which this occurred. E.g., in advanced economies competition from emerging countries resulted in job losses and downward pressure on wages in certain sectors, especially manufacturing. Delocalisation of low-skilled labour also went along with the expansion of high-paid labour in sectors like management, R&D, product design, etc., causing labour market polarisation. Hence, globalisation created winners and losers, which increased within-country inequality while at the same time decreasing between-country inequality. In other words, there seems to exist a trade-off between increasing within-country inequalities and decreasing between-country inequalities, and globalisation may have played a role in this.

Protectionism is no solution for fixing global inequality

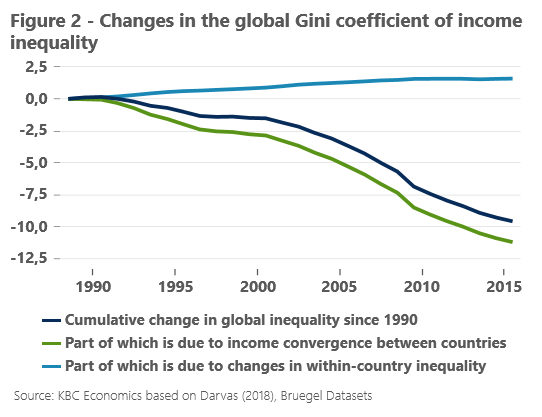

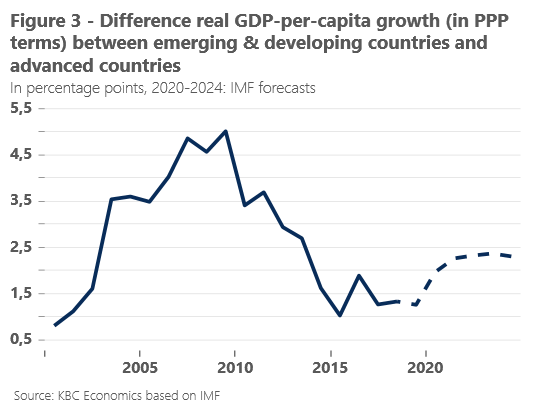

In the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008, global inequality continued to fall but at a somewhat reduced pace (figure 2). There was less of a push from income convergence between emerging and advanced countries, as the difference in GDP-per-capita growth between both groups of economies decreased (figure 3). On the other hand, the fall in global inequality has in recent years been facilitated by a stabilisation, and in some countries even a reversal, of the previous increase in within-country inequalities (World Bank, 2016, see also figure 2).

The recent reversal of the globalisation trend may have accentuated the mentioned post-financial crisis developments. Indeed, the stabilisation, and in some cases reversal, of within-country inequalities may well be linked to ongoing trade protectionism and deglobalisation, aside from country-specific factors and national policies. But the benefits of having less unequal income within countries came at the cost of reduced economic convergence of lower-income countries. According to the most recent IMF forecasts, real GDP-per-capita growth in the emerging and developing countries will again be higher than in the advanced economies in the coming years (figure 3). But the growth difference will remain far below levels seen before the financial crisis. Therefore, with protectionism and deglobalisation ongoing, the declining trend in global inequality will likely continue to be less driven by income convergence among countries.