UK economy temporarily putting up a defence against Brexit

The UK economy performed remarkably well at the end of 2017. This proves that the UK economy can withstand difficult times. UK exports are benefiting from the international economic boom and UK inflation is slightly down. The UK economy is still facing structural challenges in the longer term, particularly with regard to productivity growth, reindustrialisation, international economic integration and the bridging of the income gap.

Many studies aim to find out the impact of Brexit on the UK and the European Union. Those studies mainly focus on the long-term effects of the revised trade and investment relationships. There are many scenarios on the table, because nobody knows the eventual outcome of the current Brexit negotiations between the European institutions and the UK government. A report ordered by the UK government that was recently leaked indicated that all Brexit scenarios will have a negative impact on the UK economy. Only a soft Brexit could mitigate the impact.

While the future is uncertain, what we do know for sure is that Brexit is already having an economic impact now. That impact is mainly the result of the depreciation of the Pound sterling against the Euro since the Brexit referendum in June 2016 and increased general uncertainty during the negotiation period. When we look at the consequences for the UK economy, the depreciation of the pound sterling has both positive and negative effects. UK exporters benefit from better competitiveness on the international markets, but British consumers pay more for their imported products. This pushed up UK headline inflation (CPI) to 3% in the autumn of 2017. This exceeds the target of the Bank of England, which intervened several times, most recently a few days ago. Higher import prices have neutralised the positive growth caused by growing exports.

The real growth of the UK economy was clearly hit by falling consumer confidence and rising inflation during the second and third quarters of 2017. The clear drop in the quarterly growth figures actually made the UK growth lag behind the euro area growth. It had been quite a few years since the euro area had outperformed the UK. Due to the persistent uncertainty surrounding Brexit, it was generally assumed that the UK economy would still face (even more) difficulties in the future. What actually happened was that the last quarter of 2017 showed higher real economic growth. Unemployment remains historically low. Quarterly growth of 0.6% compared with quarterly growth of 0.5% in the two previous quarters is hardly a general recovery. However, it is still a remarkable performance, indicating that the UK economy remains resilient.

The crucial question is whether this upward movement at the end of 2017 was actually driven by better economic performance or whether it was an upward blip. Firstly, it became apparent that inflation also fell slightly to 3% in December 2017, compared with 3.1% one month earlier. The real growth increase therefore seems caused by a slowing rate of inflation. However, we do see structural improvements as well. On the one hand, the UK economy seems to be benefiting from the global upswing in growth. This has become apparent from a further increase in British exports despite a slight rise in the pound sterling. On the other hand, UK wages are on the rise and higher disposable incomes tend to encourage consumer spending.

This wage evolution is probably what concerns the Bank of England most. In principle, higher wages will slowly push up prices, which will then speed up inflation in the course of 2018. The Bank of England’s message was therefore clear: it is ready to increase interest rates somewhat earlier and by a somewhat greater extent if necessary. This seems to herald a more restrictive UK monetary policy. This monetary decision may also put a dampener on the nominal growth forecasts. Our economic outlook for the UK economy therefore remains cautious. As long as the threat of inflation has not subsided, each nominal growth improvement may be immediately cancelled out by higher inflation or may be offset in the long run by a more restrictive monetary policy.

Meanwhile, higher wage growth is good news for UK households, who will regain some of their purchasing power again. It primarily reinstates some of the purchasing power they lost following the depreciation of the pound sterling. It is a lifesaver, particularly for the low-income categories. This shows again that strong exchange rate movements offer few net macroeconomic benefits in an import-dependent, open economy.

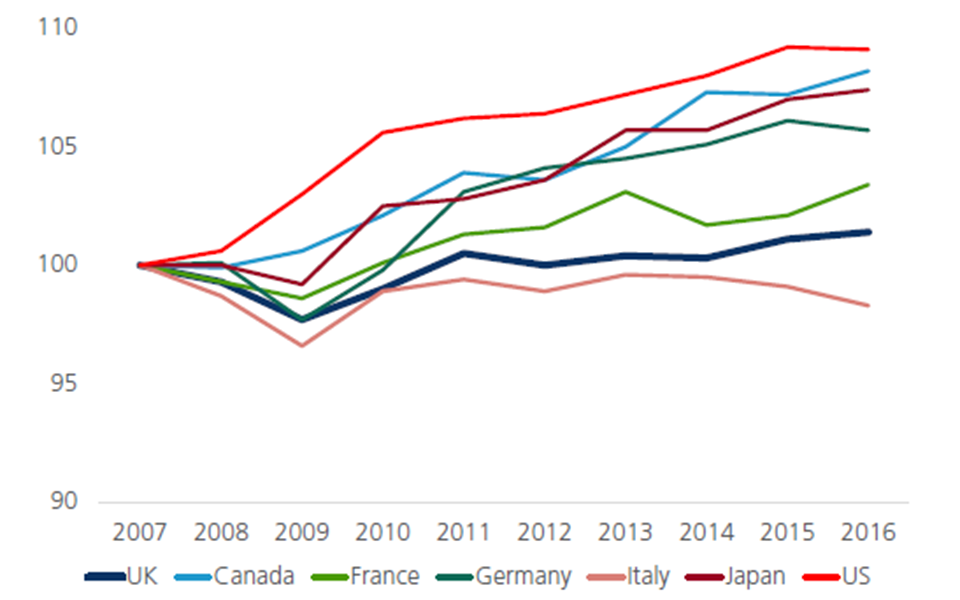

Figure 1 - Recent evolution in labour productivity in G7 countries (in constant price GDP per hour worked – index, year 2007 = 100)

Source: : KBC Economic Research based on OECD (2017)

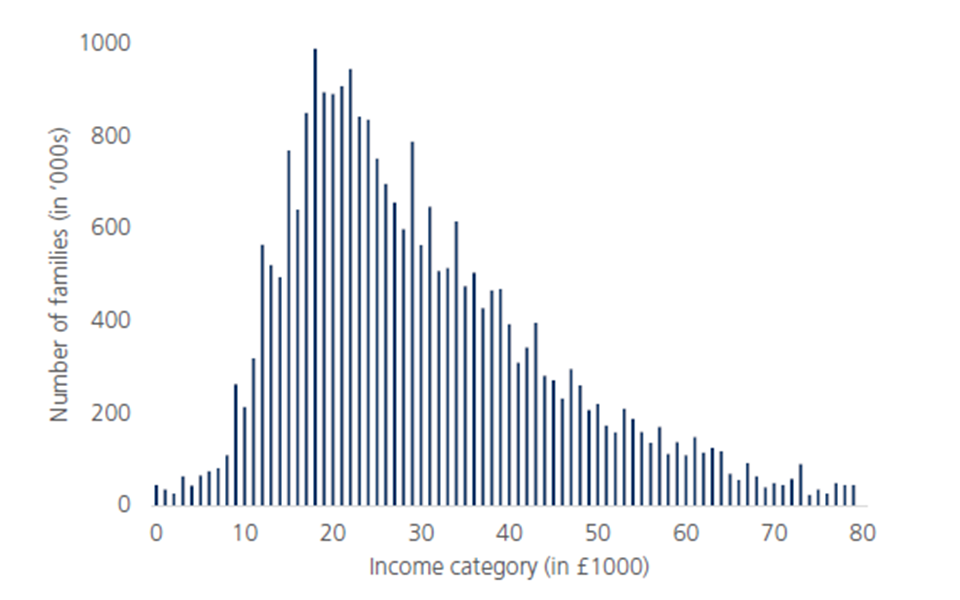

Other measures are required to strengthen the UK economy structurally. The low level of UK labour productivity compared to other western economies has long been a structural problem (figure 1). It must be said that productivity growth did improve in the course of 2017, again illustrating the UK economy’s resilience in uncertain Brexit times. However, the rise was not substantial enough to allow the UK economy to catch up quickly. This is a challenge for long-term policies. The same holds true for the reindustrialisation of the UK economy. Despite the increase in UK exports, the trade deficit has also increased. A lack of UK industrial products keeps the UK dependent on foreign products, even if prices rise substantially. Export growth may help reduce the trade deficit, but it also requires improved access to the international markets or... strong integration with the EU. Finally, rising income inequality is a painful reality. New figures for the fiscal year 2017 show that the distribution of household incomes in the UK leaves lower incomes at a significant disadvantage (figure 2). In other words, many UK households are in a difficult financial situation. In periods of economic adjustment like last year, the lowest income categories are most vulnerable.

Figure 2 - Distribution of household incomes in the UK: number of families (based on 2017 disposable income)

Source: KBC Economic Research based on Office for National Statistics (2018)

Brexit is clearly testing the UK economy and UK society. Despite the structural challenges, the recent upward movement in the UK economy shows that it is capable of withstanding difficult circumstances. However, we expect the UK economy to continue to suffer the consequences of the entire Brexit process in the short term. A solid agreement with the European Union should put an end to the uncertainty. A constructive agreement should ensure that the UK and European economies continue to support each other.