Banking turmoil an excuse for Fed to skip a rate hike

The June FOMC meeting is just around the corner. After a year and a quarter, it will probably be the first meeting of the US central bank without a rate hike. Ironically, this will happen in the context of still strong macroeconomic data. One of the important arguments for why the Fed might pause (or skip) further monetary tightening in this situation, is that other types of tightening may be underway in the US economy. There is a possibility (risk) that the March banking mini-crisis has started a further tightening of credit standards, which may ultimately lead to a slowdown in lending activity and the economy. Hence, the question that Fed officials need to ask is whether there is a negative credit supply shock in the US economy and, if so, whether it can substitute for additional monetary tightening whether in the form of further rate hikes or ongoing quantitative tightening.

We tried to answer this question through our simple macroeconomic model that identifies credit supply shocks in addition to monetary policy shocks. The output of the model shows us that the slowdown in credit activity that followed the US banking mini-crisis could represent a +25bps additional hike to the Fed funds rate. Such a quantification of the spring credit shock is of course not straightforward and surrounded by great uncertainty, but given that some US policymakers (e.g. San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly) have commented on the impact of the banking mini-crisis in a similar fashion, we consider the result of our model plausible, and (qualitatively) in line with the FOMC conclusions.

Tighter credit standards

As can be seen in figure 1, according to the Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices (SLOOS), credit standards for commercial and industrial loans have been tightening since the beginning of 2022. Moreover, the April SLOOS report included ad hoc questions specifically addressing banks' outlooks for lending standards over the remainder of 2023. Reporting banks expect to tighten standards across all loan categories - citing an expected deterioration in the credit quality of their loan portfolios and in customers' collateral values, a reduction in risk tolerance, and concerns about bank funding costs, bank liquidity positions, and deposit outflows. All this could make US rate-setters more cautious as they might be afraid that a negative credit supply shock could slow the US economy even more.

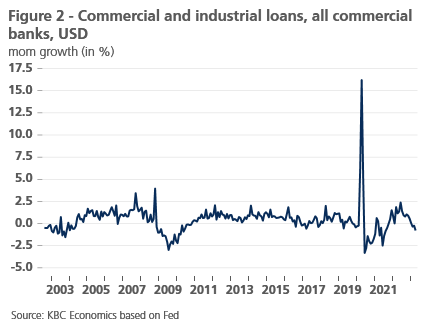

And – when we check the actual credit data – growth of commercial and industrial loans has turned negative since the beginning of this year, although the drop in credit growth has been limited, certainly compared to negative credit growth during past US recessions.

When trying to assess the consequences of recent US banking turmoil and potentially lower credit growth on real GDP growth, inflation, and US monetary policy, a first question we should ask is: Is the decreasing credit growth in commercial and industrial loans (mainly) attributable to credit supply shocks? The answer is important. If this drop is driven by recent negative credit supply shocks, this is a reason for the Fed to adapt its monetary policy. If this drop is driven by past negative aggregate supply or monetary policy shocks, then this drop in loans/credit is not a surprise to the Fed and not a reason to change its monetary policy.

To answer this first question, we try to identify1 the underlying shocks driving the US economy. We distinguish four types: aggregate demand and supply shocks, a monetary policy shock and a credit supply shock – the latter representing recent banking turmoil (see the table below). If a negative credit supply shock is measured, we can analyse the effects of this shock on inflation and monetary policy.

| Demand | Supply | Monetary Policy | Credit Supply | |

| GDP growth | + | + | + | + |

| Inflation (CPI) | + | - | + | + |

| Shadow Fed Funds Rate | + | - | + | |

| Lending Rate | + | - | ||

| Loanvolume | + |

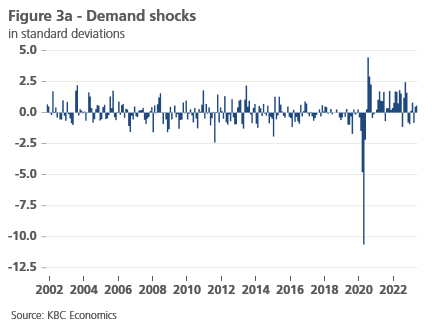

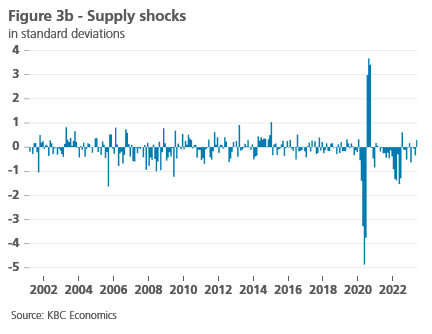

In figure 3, the underlying shocks hitting the US economy are shown (as identified by the model). Figure 3a gives an impression of the post-covid excess demand, partly caused by government fiscal spending. In Figure 3b, the negative supply shocks can be observed – a visualization of the energy crisis and supply chain disruptions. Figure 3c shows the behaviour of the Fed. In 2021, we observe positive monetary policy shocks. The Fed, in other words, allowed for more inflation in order to support economic growth compared to past behaviour. In 2022 we saw the opposite, described here as negative monetary policy shocks. Recall that we aim to capture shocks that would represent both conventional and unconventional monetary policies (e.g., quantitative easing or tightening). Hence, we used Krippner’s shadow policy rate 2 instead of the effective Fed Funds rate in the model.

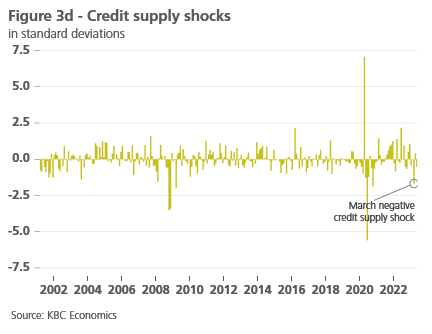

Those negative monetary policy shocks and supply shocks have a negative effect on credit growth in the US. Part of the drop we see in commercial loan volume is therefore no surprise to the Fed -- it is part of their plan to fight inflation. Nevertheless, a significant negative credit supply shock was measured in March, as can been seen in figure 3d. Based on incomplete data for the second quarter, no significant additional negative credit shock can be measured.

Consequences for economic growth and inflation

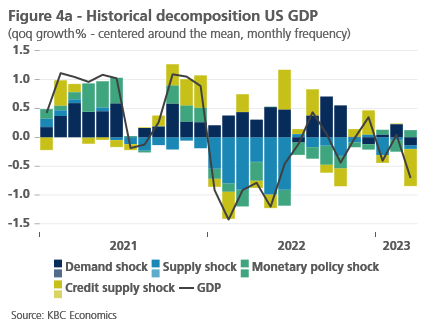

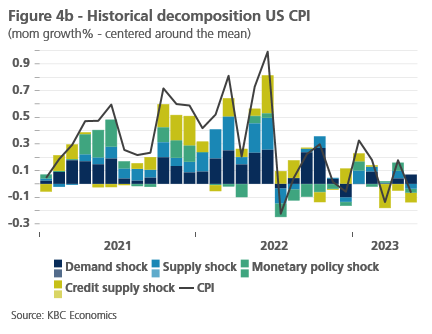

A negative credit supply shock can dampen business investment as companies find it more challenging to obtain financing for capital expenditures and expansion projects. Reduced job creation can potentially impact consumer spending. In other words, the impact of negative credit supply shocks on GDP is expected to be negative. The consequences for inflation are less straightforward, however. Yes, reduced investment and consumer spending can dampen overall aggregate demand in the economy. Lower demand can put downward pressure on prices, as businesses may need to lower prices to attract customers and stimulate sales. On the other hand, a negative credit supply shock can also have supply-side effects. If businesses face difficulties in obtaining credit to finance their operations, it may impede their ability to invest in productivity-enhancing measures, such as technology upgrades. However, the latter is a medium or long-term problem. In the short term, demand effects usually dominate. The effect of the negative credit supply shocks on inflation is, indeed, measured to be negative, as can be observed in figure 4. The drop in economic activity and inflation below their trend in March, is the consequence of the negative credit supply shock.

FED reaction

Now that the banking crisis seems to be contained, we believe the Fed could still ask itself what the overall effect of credit tightening on the economy has been. Fed Chair Powell has not given a clear, unambiguous, answer to this question. San Francisco Fed President Mary Daly, however, was more specific as she spoke about the equivalence of one to two rate hikes.

Historically, looking at the impulse response functions of the model and the size of the negative credit supply shock, the Fed would cut rates by 25 basis points in the short-term (or extend quantitative easing with an equivalent magnitude). When calculating the size of a monetary policy shock needed to have the same effect on inflation as the March negative credit supply shock, we would end up with the same conclusion (the Fed would have to raise interest rates by 25 basis points to get the same effect on inflation). This time, conclusions from a similar exercise might lead some dovish Fed officials to argue that a negative credit effect of the banking turmoil might compensate (some) other forms of the tightening. So, it would be better to skip a rate hike this time and to wait-and-see for more macro and banking figures including those on loans and credit standard surveys.

1 A SVAR model is estimated, shocks are identified based on the sign restrictions described in Finck, David, and Paul Rudel. "Do credit supply shocks have asymmetric effects?." Empirical Economics (2022): 1-39.

2 Krippner, Leo. "Measuring the stance of monetary policy in zero lower bound environments." Economics Letters 118.1 (2013): 135-138.