A worrying look at Belgium’s public finances

- 1. Current state of Belgian public finances

- 2.Debt ratio on an unsustainable path

- 3. Why too much debt is not good

- 4. Budget consolidation

Read the publication below or click here to open PDF

Extract

Over the past three years, Belgium's public finances have been under severe pressure due to successive crises. Expressed as a percentage of GDP, public debt did fall sharply in 2022 due to high inflation, but the continuing high primary deficit causes the debt ratio to rise again from 2023 onwards. With unchanged policies, the public deficit will further thicken in the coming years due to, among others, ageing costs. This will most likely put the public debt on an unsustainable path. From a European perspective, Belgium also scores rather badly on public finances. The Belgian government now faces the tough task of restoring financial sustainability. A consolidation is necessary to create room for new policy and to cope with many challenges, including the ageing population. It requires more fiscal discipline than in the past, as well as more ambitious structural reforms. The latter should ensure that more people are in work, the economy's growth potential is strengthened and the efficiency of government is improved.

Several bodies, including official ones such as the NBB and the Federal Planning Bureau, recently highlighted the worrying state of Belgium's public finances. Both the current situation (i.e., a high structural deficit and a debt ratio rising again from 2023 onwards) and the longer-term sustainability are of great concern in light of the various challenges we face. These concern not only ageing, but also others such as climate change, the changed geopolitical situation in Europe or the need to upgrade infrastructure. In this article, we take a broad, worrying look at Belgium's public finances. Section 1 considers its latest development and places it in a European perspective. Section 2 illustrates that Belgium’s finances, and the debt ratio in particular, risk ending up on an unsustainable path under an unchanged policy assumption. In section 3, we argue that such evolution implies important consequences and risks. Section 4 focuses on the necessary and severe restructuring of finances that the Belgian government will have to implement.

1. Current state of Belgian public finances

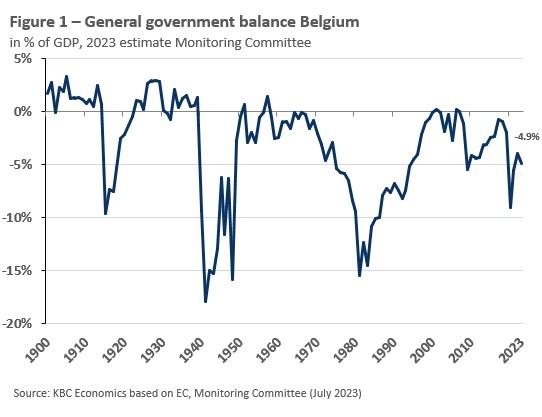

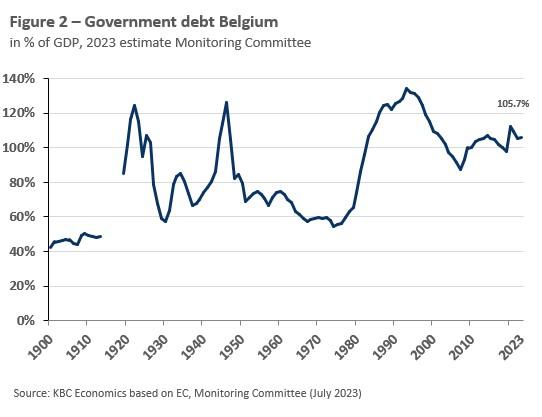

The rapid succession of the covid and energy crises in recent years has severely impacted Belgium's public finances. In 2019, the public deficit and public debt of the combined Belgian government were 2.0% and 97.6% of GDP, respectively. In 2020, both peaked at 9.0% and 112.0%. The situation improved in 2021-2022, but in 2022, the deficit and debt remained sharply above pre-pandemic levels at 3.9% and 105.1%. Moreover, according to the Monitoring Committee's latest estimate (published in mid-July), the figures will deteriorate again to 4.9% and 105.7% of GDP in 2023 (see Figures 1 and 2). Earlier this year, the European Commission in its spring forecast (published in mid-May) estimated the deficit and debt for 2023 at 5.0% and 106.0%, respectively.

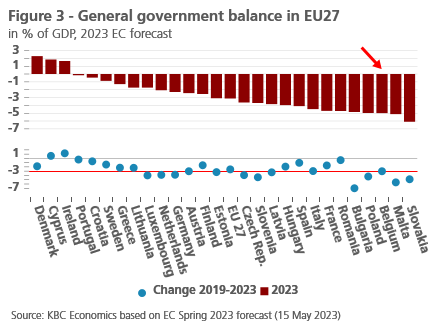

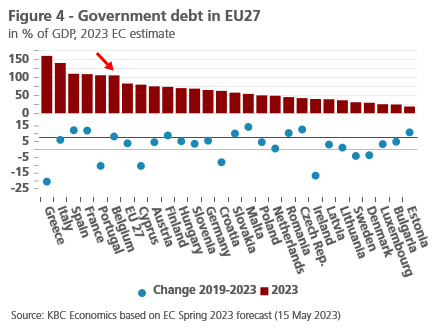

From a European perspective, the deterioration of Belgium's public finances was more pronounced than the EU average. If we factor in the European Commission's latest public finance projections for 2023, the increase in deficit and debt between 2019 and 2023 in Belgium would be 3.0 and 8.4 percentage points of GDP, respectively, on balance. In the EU as a whole, it is only 2.6 and 4.0 percentage points of GDP, respectively (see Figures 3 and 4). With a government deficit projected by the Commission at 5.0% of GDP in 2023, Belgium scores the worst figure in the EU except for two countries (Malta and Slovakia).

Belgium's relatively poor performance has to do in part with the operation of the so-called "automatic stabilizers”. These are built-in mechanisms in public finances (including the unemployment benefit system) that ensure that fluctuations in the economic cycle are mitigated without active government intervention. According to an estimate by the OECD, Belgium is among the European countries with a rather strong automatic damping of the impact of shocks on the business cycle, which translates into public spending and revenues.1 With specific measures designed to mitigate the impact of the crises on households and businesses (e.g., the extension of temporary unemployment during the pandemic), the stabilizing effect has been (temporarily) reinforced in recent years. However, because economic growth in Belgium held up somewhat better than in the EU as a whole during the past crises, the difference between Belgium and the EU in terms of change in the cyclical component of the government balance in the period 2019-2023 remained limited overall.

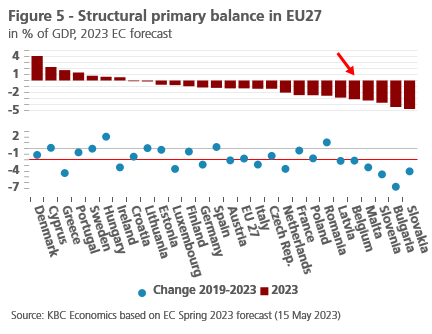

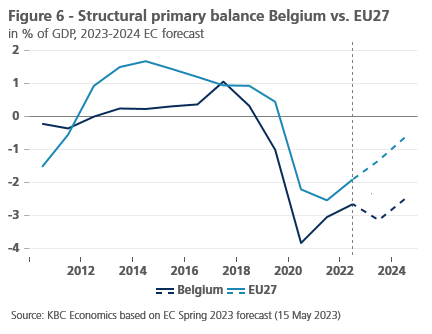

The relatively sharp deterioration of Belgium's public finances was due more to an expansive fiscal policy than to the impact of the business cycle. In part, this was due to the exceptional government support needed to deal with the consequences of the crises. This crisis policy ensured that Belgium came through the past difficult period relatively well from an economic point of view. The fiscal policy effectively implemented is generally measured by the change in the structural primary balance (i.e., the general government balance adjusted for cyclical influences and interest payments).2 The sharper deterioration of this balance in Belgium, compared to the EU as a whole, points to a relatively firm discretionary policy response in Belgium over the past few years (see Figures 5 and 6).

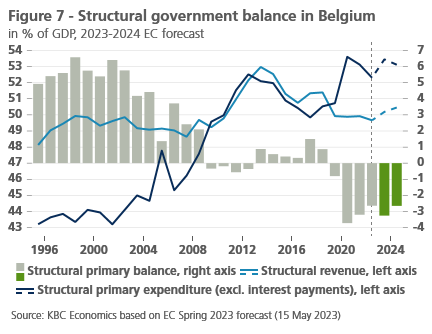

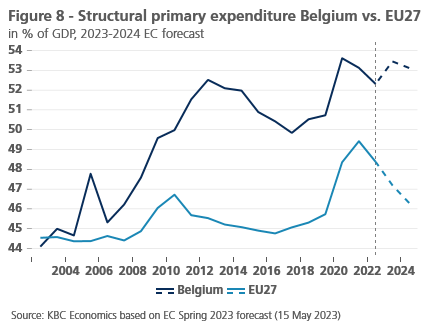

It is notable that structural spending in Belgium has increased not only since 2019, but also on a longer-term trend relative to the EU (see Figure 8). Moreover, according to the European Commission's latest projections, structural spending in Belgium will remain at a high level in the coming years, in contrast to the EU as a whole where it is expected to return to pre-crisis levels. Consequently, even after the lifting of the temporary crisis interventions, a fairly large structural government deficit is still expected in the coming years under unchanged policies. The situation is worrisome because it implies a structural upward movement of debt dynamics.

2. Debt ratio on an unsustainable path

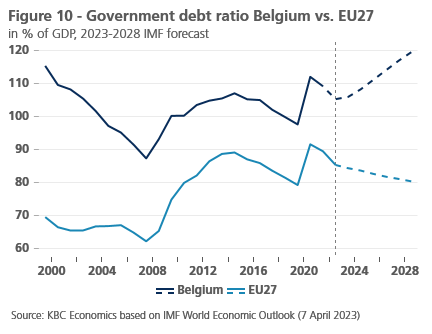

Belgium's debt ratio is expected to remain among the highest in Europe at around 106% of GDP in 2023. In the EU, Greece and Italy have much higher levels of debt, while Spain, France and Portugal have similar but slightly higher ratios than Belgium. Compared to the EU average, Belgium's debt ratio is as much as 23 percentage points higher. Belgium's high debt is an old structural problem. Over the past century, the gross debt ratio never dropped substantially or permanently below the 60% limit that Europe sets as its numerical target (see Figure 2). Only between the mid-1960s and the late 1970s was the ratio close to it for a time. The average level of Belgium's debt ratio has been around 90% of GDP since 1920.

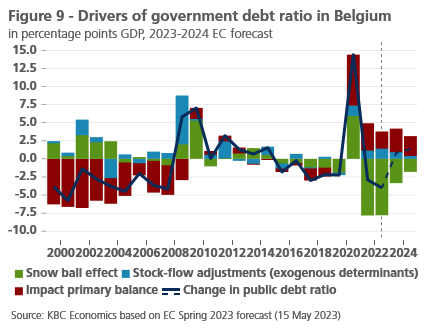

After peaking in 2020, Belgian debt declined for two consecutive years, giving the positive impression that the rate was on a downward path. However, the decline in 2021 and 2022 was due to the exceptionally strong nominal GDP growth and, more specifically, its price component, which was a result of the strong inflation surge. This was reflected in a higher denominator that reduced the debt ratio. Combined with the historically low implicit interest rate on government debt, the high nominal GDP growth rate created a so-called "reverse snowball effect" (g > i).3 In addition, endogenous debt change is also determined by the size of the primary balance (i.e., the balance excluding interest payments on the debt). High primary deficits continued to fuel the Belgian debt ratio in 2021 and 2022 (see Figure 9).

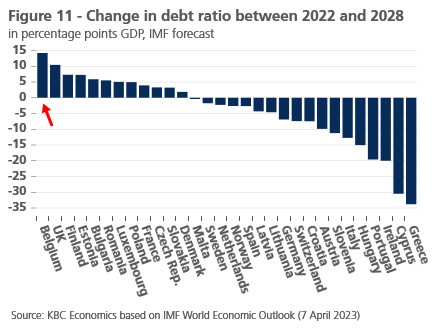

Now that inflation is gradually normalizing, the reverse snowball effect is coming to an end. As a result, the debt ratio is likely to start rising again from 2023 onwards due to the persistent primary deficits. Unlike the European Commission, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) makes numerical projections on public finances through the medium term, i.e. until 2028. According to the latest IMF projections (published in mid-April), the Belgian government’s debt (under a no-policy-change assumption) would rise to 119.5% of GDP by 2028, while across the EU as a whole, it would decline to 80.4% of GDP. This makes Belgium the EU country with the strongest debt increase (in percentage points of GDP) between 2022 and 2028 (see Figures 10 and 11).

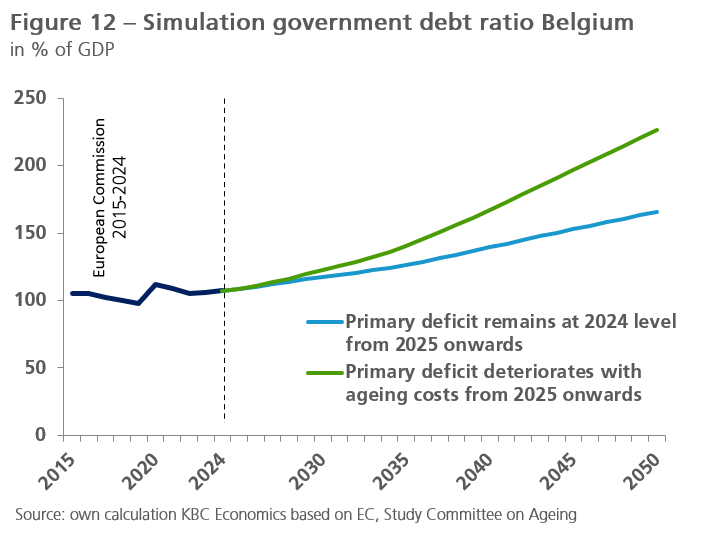

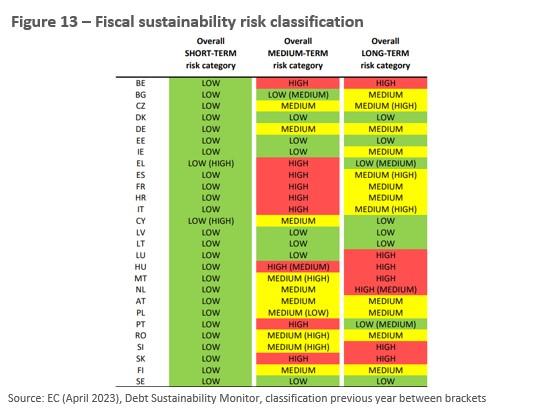

A major cause of the structural deterioration of public finances concerns the increasing cost of an ageing population (mainly concerning pensions and health care). According to the Study Committee on Ageing (Annual Report 2023), this annual cost will increase by 4.4 percentage points of GDP over the period 2022-2050 if the policy remains unchanged. In Figure 12, we simulate the long-term evolution of Belgium's debt ratio until 2050, assuming that the primary balance deteriorates from 2024 onwards to the extent of this ageing cost estimated by the Study Committee. The debt ratios for 2023 and 2024 refer to the latest European Commission projections.4 The figure illustrates that, if policy remains unchanged, the cost of ageing would cause the Belgian debt ratio to rise sharply over the coming decades. That Belgian public finances are on an unsustainable path with unchanged policies is also confirmed in the European Commission's latest Debt Sustainability Monitor (published April 2023). In it, Belgium is seen as one of the EU countries, along with Hungary and Slovakia, for which the Commission identifies a high risk of unsustainable public debt in both the medium and long term (see Figure 13).

3. Why too much debt is not good

Government debt in itself is not bad. It is acceptable if it makes it possible to increase the productive capacity of the economy and if the return from debt-increasing government interventions (investment in infrastructure, education, security, etc.) is larger than the cost generated by the debt (the interest burden). However, excessive debt implies significant economic risks. First of all, doubts may arise about the sustainability of the debt, more specifically about repayment and interest payments (the so-called solvency risk), especially when, as in Belgium, high costs linked to ageing appear. Ultimately, the entire financial system may end up in crisis, as banks are traditionally major consumers of public debt in which they invest part of the savings deposits collected. The adjustments required to reduce an out-of-control debt position are usually substantial and potentially dramatic for the population. The 2010-2011 sovereign debt crisis in the eurozone, and in Greece in particular, is a painful illustration of this.

Specifically, high debt makes public finances vulnerable to a rise in interest rates over time, especially during a period of fiscal consolidation. A larger share of revenues must then serve to provide interest payments, so that other expenditures, often including more productive ones such as infrastructure investments, are squeezed (the so-called cuckoo effect), unless the tax burden is increased. More generally, high interest costs and/or the need for remediation imply reduced policy capacity to deal with future new shocks and challenges. Furthermore, if debt rises sharply, interest rates will in turn tend to rise, inhibiting private investment.

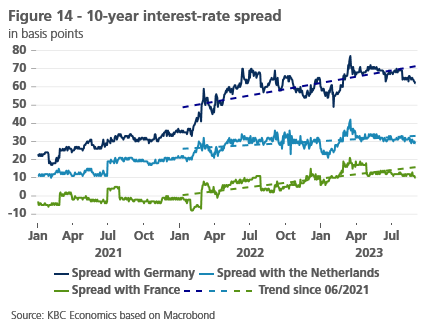

In line with the sharp rise in 10-year bond yields since 2021, implicit interest rates on Belgian government debt will also begin to rise from 2023. However, the extent of this is somewhat mitigated by the fact that the Belgian treasury has taken advantage of the earlier lower interest rate environment to refinance outstanding debt at very low interest rates. In the process, the average maturity of the outstanding debt portfolio increased from less than 6 years in 2010 to currently above 10 years. Despite the high level of public debt, Belgium still maintains market confidence. Nevertheless, recently the perception of Belgium's public finances by financial markets seems to be reversing somewhat. Over the past year and a half, the 10-year OLO interest rate spread widened not only against Germany (as was the case for most other European countries), but also against the Netherlands and France (see Figure 14).

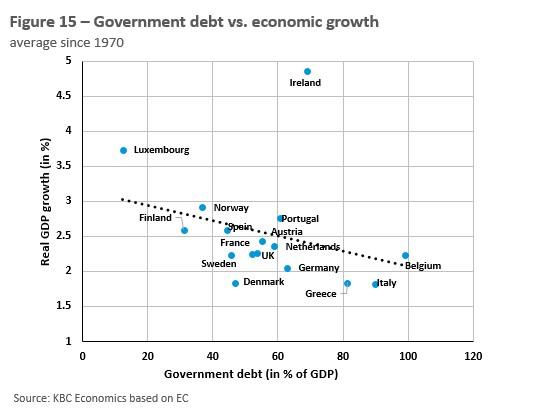

Finally, note that economic growth can also be negatively affected by all this. This is even more the case if citizens would start saving more in anticipation of higher future taxes to pay off high debt (the Ricardian equivalence theorem). However, opinions vary widely on the extent to which high public debt cripples growth.5 Some economists suggest a negative, nonlinear relationship in which growth becomes much weaker as the debt ratio gets very high. Other economists question that conclusion. Their criticism concerns causality. It is not because a relationship between high debt and low growth is established that low economic growth was caused by high debt. It may be that, conversely, low growth leads to high government debt because less taxes are collected and more spending is incurred.

Figure 15 confirms that while there appears to be a negative relationship between debt and growth among a group of European countries over a long period of time, it is not very strong. If a critical threshold exists at all beyond which debt begins to stifle growth, it is likely to vary from country to country, depending on specific economic and institutional characteristics. Indeed, factors such as weak institutions, low competitiveness or a fragile banking sector help determine the extent of the impact that high public debt has on economic growth. These factors help determine the overall financial and economic stability of the country in question. Belgium does not usually score badly, in some cases even well in these areas. In other words, the high public debt is offset by the favourable overall financial situation of the Belgian economy, thanks to a relatively healthy private sector. This puts the economy as a whole (households, companies and government together) in a positive financial net asset position compared to the rest of the world. At the end of 2022, that so-called Net International Investment Position reached 54% of GDP, the highest figure in the EU after the Netherlands and Germany.

In the coming years, the Belgian government faces the difficult task of reducing the structural primary deficit in order to put the public debt back on a sustainable path. The consolidation is necessary to create room for new policies and to respond to the various challenges we are facing. These challenges include not only the ageing population, but also climate change, the changed geopolitical situation in Europe that will require more military spending, the upgrading of infrastructure, and probably others that we do not know about today. Indeed, the environment in which we live is becoming more and more complex, and this increases uncertainty about public policy and also public finances.

It seems that the new European budgetary rules will in any case force Belgium into a hard consolidation. The broad outlines of the new European budgetary framework were already proposed by the European Commission in April 2023, but they have not yet been approved. In principle, the new rules should take effect from 2024, after a long period during which the current rules were suspended due to the pandemic and the energy crisis (via the so-called Escape Clause). The reform would give each EU member state a four-year plan tailored to put debt on a declining path. Countries can opt for a slower path over seven years, provided they make credible investments and reforms that improve debt sustainability. The Commission wants to focus more on the evolution of public spending and on the obligation to squeeze at least 0.5 percentage points annually from the budget deficit if it is above the 3% of GDP limit. For Belgium, the new rules would imply a substantial consolidation of about 0.8% of GDP per year. To spread the consolidation over a longer period (seven years), Belgium must agree to ambitious and detailed reforms with the Commission.

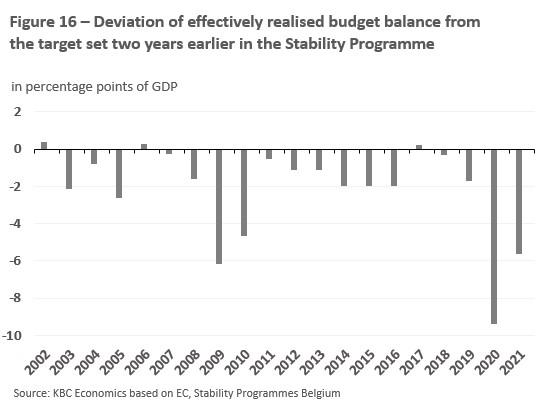

The government has already committed in the latest Stability Programme (submitted to Europe in April 2023) to reduce the structural deficit from an estimated 4.6% of GDP in 2023 to 2.7% in 2026. By comparison, according to the latest Monitoring Committee estimate, the structural deficit (on a no-policy change basis) would reach 4.5% of GDP in 2026, rising further to 4.9% in 2028. For the necessary consolidation to succeed, more fiscal discipline will be needed than in the past. Since 2000, the Belgian government has met its own fiscal target from the annual Stability Programme only a few times (see Figure 16). There have been shocks (specifically the financial crisis, the pandemic and the energy crisis) that were responsible for this. That said, it also failed to meet its own target in the intervening years when the economy was doing well. We can less afford such lack of discipline in the coming years, given the current worrisome state of finances and the costs associated with the challenges ahead.

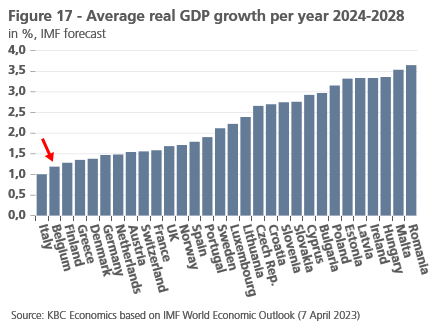

The higher the economic growth, the easier it will be to restore sound finances. If the IMF's medium-term projections are to be believed, Belgium's average GDP growth will be among the lowest in the EU in 2024-2028 (see Figure 17). To avoid such a scenario, the growth potential of the Belgian economy must also be strengthened. To this end, additional reforms (e.g., concerning the labour market) and investments (e.g., concerning infrastructure and high-performance education) remain necessary in the coming years. More generally, through reforms, it remains important to create a favourable environment in which companies invest, innovate and create jobs and it pays for citizens to fill those jobs. In doing so, further efforts must be made to increase the employment rate. According to the latest estimate by the Study Committee on Ageing, with unchanged policies, the employment rate will reach 75% by 2030. This figure implies a still wide gap with the 80% target set by the government in the coalition agreement.

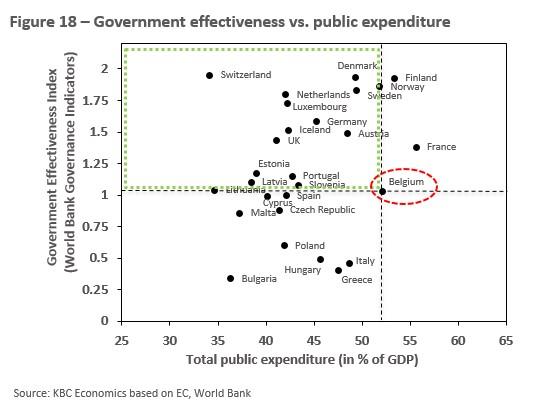

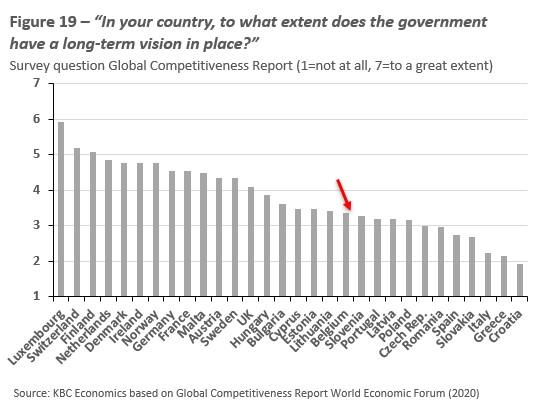

Last but not least, continued attention must be paid to increasing government effectiveness. Despite relatively high government spending, the public sector in Belgium is relatively inefficient. Many European countries score (much) higher than Belgium on the World Bank's Government Effectiveness Index despite (much) lower government spending (see Figure 18). The rather low government effectiveness is partly related to a lack of sharp and stable policy goals and priorities (see Figure 19). There is a need for more long-term vision in policy focused on what is really important socially and economically, especially in light of scarce public resources.

1 See A. Maravalle and L. Rawdanowicz (2020), “How effective are automatic fiscal stabilisers in the OECD countries?”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers no. 1635

2 The support measures taken to limit the economic impact of the crisis are not counted as one-off and temporary measures (the so-called 'one offs'), in accordance with the European guidelines under the Escape Clause. Consequently, they are partly counted as part of the structural balance (partly as expenditure on temporary unemployment belongs to the cyclical component).

3 Mathematically, the endogenous change in the debt ratio is represented by: Dt - Dt-1 = Dt-1 x (it-gt)/(1+gt) – Pt where Dt, Dt-1 = the debt ratio at the end of year t and t-1 respectively; it = the implicit interest rate on government debt in year t (i.e., interest payments in year t divided by the debt in year t-1); gt = nominal GDP growth in year t and Pt = the primary government balance in year t. The formula shows that even in the absence of a primary deficit, the debt ratio increases (decreases) when the interest rate on outstanding debt is larger (smaller) than nominal GDP growth. This mechanism of automatically thickening (shrinking) the debt is called the (reverse) snowball effect.

4 For annual real GDP growth, we also take figures from the Study Committee on Ageing. We set inflation (based on the GDP deflator) at just above 2% in the medium and long term. Finally, we let the implicit interest rate on debt gradually rise to 3.7% in 2040 and leave it unchanged thereafter.

5 For a recent overview of the literature on this topic, see P. Heimberger (2022), “Do higher public debt levels reduce economic growth?”, Journal of Economic Surveys.