EU’s efforts to reduce dependency on Russian energy supplies

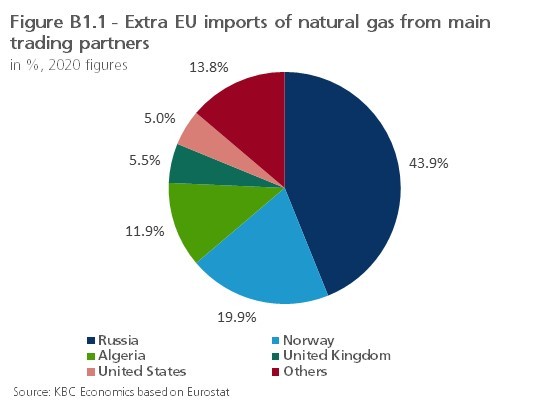

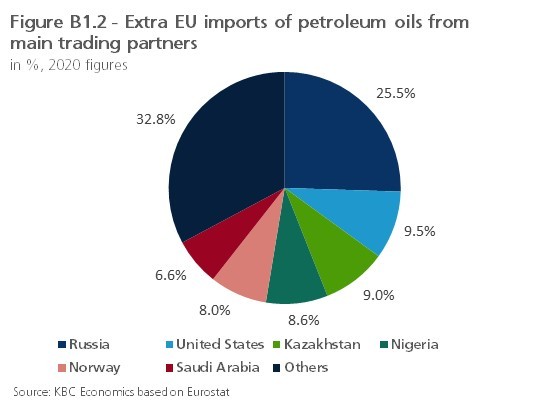

The European Union’s dependency on Russian energy imports, in particular natural gas and crude oil, has been a longstanding concern. Russia accounts for more than 40% of gas imports (figure B1.1) and around 25% of oil imports (figure B1.2), though there are significant cross-country differences.

After almost two months of Russian aggression in Ukraine, the political pressure to reduce energy imports from Russia is on the rise, and there even appears to be a broad agreement that energy imports from Russia should be reduced. However, there is less agreement on the scale and the pace that a reduction should proceed, with several member states, including Germany and Hungary, blocking a full import embargo.

In general, the European Union’s ability to switch away from Russian supplies is greater for oil than for natural gas. This is largely because more than two-thirds of Russian oil exports into Europe are via seaborne routes, implying greater logistical flexibility. Furthermore, there are ample strategic petroleum reserves equal to at least 90 days of net imports. On the other hand, around 95% of Russian gas exports are transferred into Europe via pipelines. Unlike oil, there are no strategic gas inventories to draw upon, and there are significant infrastructural and logistical barriers to rapidly ramp up imports of LNG.

In March, the European Commission put forward a proposal (REPowerEU) to reduce dependency on Russian gas and make the EU independent from Russian fossil fuels well before 2030. This plan outlines a series of measures, including a requirement to replenish gas storage to at least 90% of its capacity by 1 October each year. The EC seeks to diversify gas supplies via higher LNG and pipeline imports from non-Russian producers. In addition, the EC proposes to speed up the roll-out of renewable gases and to replace gas in heating and power generation. According to the EC, all these measures can reduce EU demand for Russian gas by two thirds before the end of 2022.

These aspirations for increased EU’s energy independence seem particularly challenging over such a short horizon. To begin with, most Russian oil and gas imports are contracted under long-term commitments, meaning that without explicit contract terminations (or alternatively force majeures), the decoupling could take some time. In addition, there seems to be a trade-off between the pace of decoupling and its costs: the more rapidly the EU seeks to reduce Russian imports, the higher global energy prices likely will increase (and the larger the drag on economic growth). An abrupt shut-off of Russian energy exports to Europe would likely push the continent into economic recession.

Importantly, there appears to be a case for coordinated action on the EU level to avoid a situation in which member states are bidding against each other to secure alternatives to Russian energy supplies, making them even more expensive. At the same time, a reduction in Russian energy imports is set to affect some countries more than others (the most exposed is the CEE region), possibly necessitating some fiscal action undertaken at the level of the EU as a whole.

Finally, the scale and speed of the transition away from Russian energy supplies are set to be influenced by the evolution of the war in Ukraine. The more intense and extended that war is, the stronger the political pressure will be to cut imports from Russia more aggressively.