Emerging markets quarterly digest: Q3 2020

Read the publication below or click here to open the PDF.

Emerging markets quarterly digest: Q3 2020

Overview

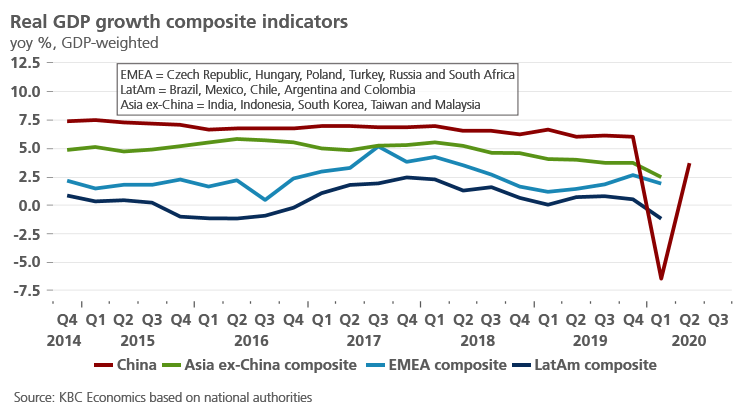

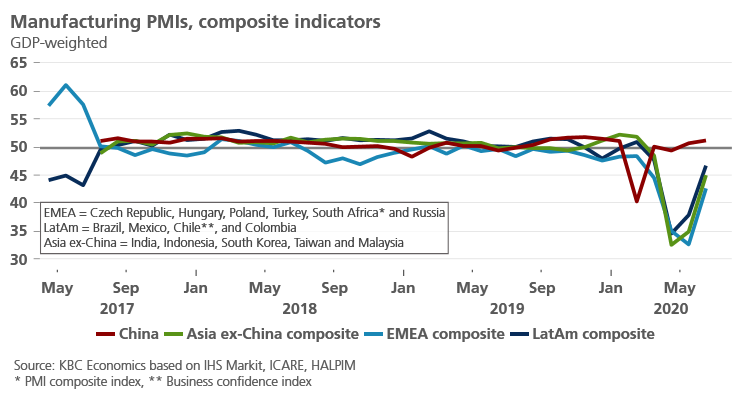

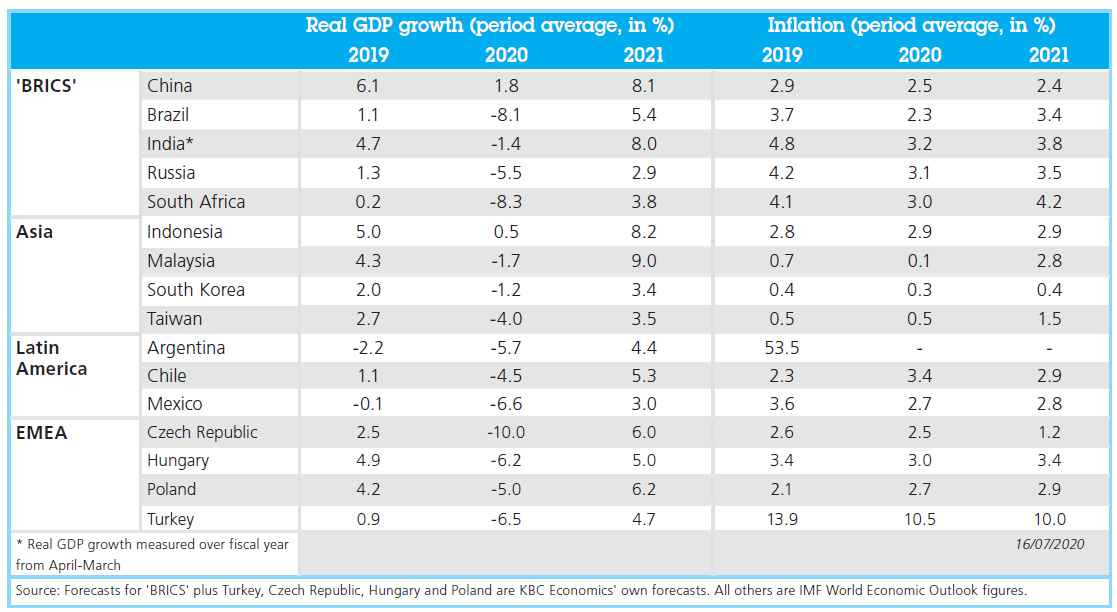

Emerging markets, like advanced economies, continue to weather the health crisis and subsequent economic fallout inflicted by the Covid-19 pandemic. Aside from China, which entered and exited its economic shutdown a few months earlier than the rest of the world, and which appears to be on track for a ‘V-shaped’ recovery, the rest of the world is expected to see a more-or-less synchronized but gradual recovery starting in Q3 2020, following an incredibly steep and sharp recession in Q2.

But although almost all countries in the world are facing a similar challenge at the moment, it is still crucial to highlight the substantial heterogeneity among emerging markets in the current context. As is becoming increasingly clear, there are important variations in both the ways in which emerging markets are tackling the health crises and the ways in which their economies are responding to the pandemic-induced recessions.

From a regional perspective, Latin America has been hit hard by the pandemic and will likely face a slower recovery path compared to economies in Asia or Europe. Within Asia, however, there is also important heterogeneity. India and Indonesia are struggling to get the virus under control, while East Asian and other Southeast Asian countries have kept their numbers relatively low. A similar division holds for external vulnerabilities, which can impact a government’s or monetary authority’s ability to implement adequate policy support. Taiwan, Thailand, Vietnam, South Korea, Russia, Malaysia, Poland, China and the Czech Republic all boast current account surpluses, while Colombia, Chile, Brazil, South Africa, Indonesia and India all have current account deficits. Figure 1 summarizes these and other vulnerabilities, as well the depreciation or appreciation each country’s currency has seen versus the USD this year.

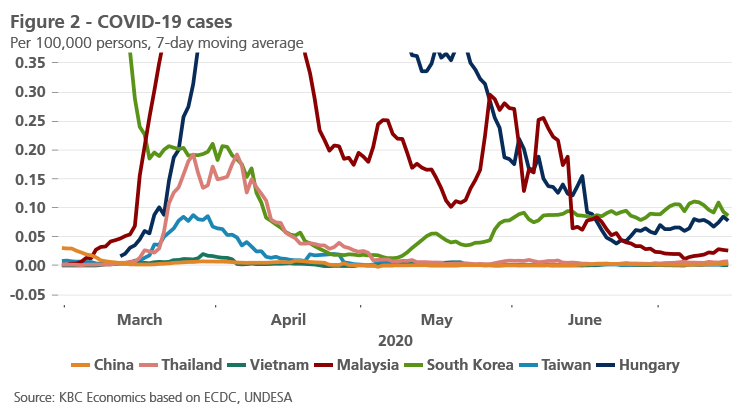

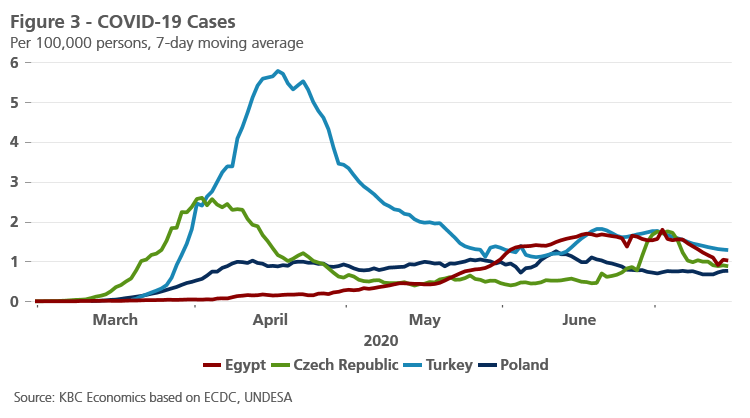

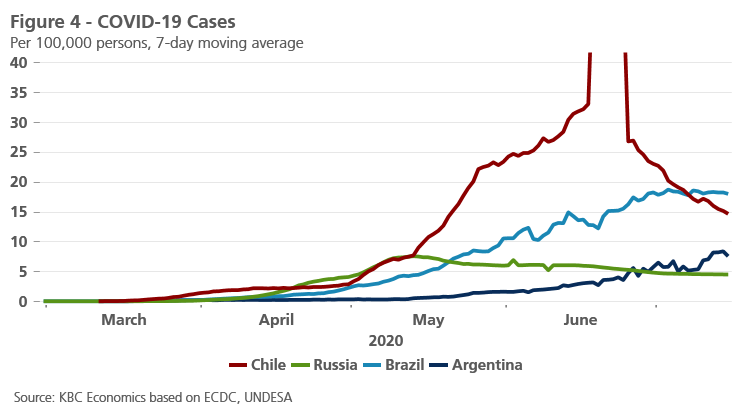

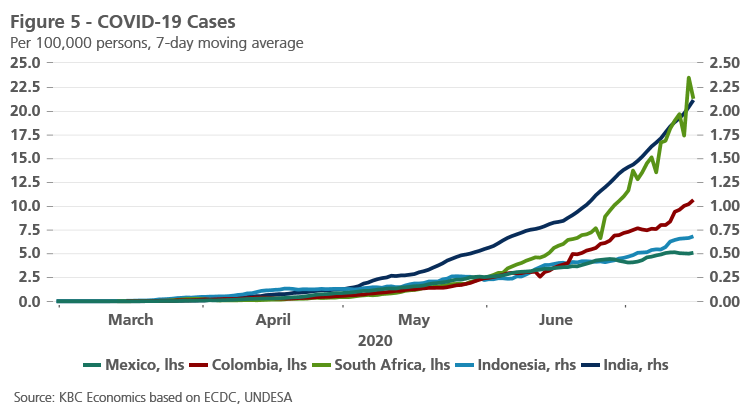

Battling the virus

The trajectory of the spread of the virus in each country is of course an important element in attempting to forecast the respective strength and pace of each economic recovery. For this purpose, the major emerging market economies can be roughly categorized in four groups at the current moment (with a caveat that developments related to the virus can change quickly). First, there are countries where daily case numbers per capita are relatively low and appear to be staying low (below 0.15 cases per 100,000 people). This group consists mostly of East Asian and Southeast Asian countries like China, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, Taiwan and South Korea (though the latter is seeing some upward trend that remains muted compared to the rest of the world). The second group of countries appear to have stabilized daily confirmed case numbers per capita at slightly higher but still moderate levels (below 1.5 cases per 100,000 people). This includes several EMEA (Europe, Middle East and Africa) economies like Poland, the Czech Republic, Turkey and Egypt. The third set of countries have seen daily cases moderate or just start to peak at relatively higher levels (4.5-20 cases per 100,000 people). These countries include Chile, Argentina, Brazil and Russia. Finally, there are several emerging markets where the number of daily cases per 100,000 people is still rising sharply, including Indonesia (0.7), India (2.0), Mexico (5.0), Colombia (10) and South Africa (23) (figures 2-5).

In many ways these developments are consistent with the relative strength of public health systems in these economies. As we noted in the previous edition of this digest, India, Indonesia and Colombia all have low per capita expenditures on healthcare according to the World Bank. Countries with high poverty levels, like South Africa and Mexico, may also find it more difficult to implement social distancing measures that help slow or stop the spread of the virus.

Vulnerabilities are still important

One might also expect that poorer countries with more limited fiscal space for maneuver may find it more difficult not only to combat the health crisis brought on by Covid-19, but also to finance much needed stimulus to protect businesses and individuals and promote a strong recovery. Indeed, the G20 moratorium on bilateral debt payments from the lowest income countries until the end of the year was an important step in this regard (although the debt payments have only been delayed, not forgiven). Meanwhile, the World Bank has also set up a fast track facility to provide financing to 100 developing countries. The IMF also reports that 102 countries have come to the institution for financing support during the crisis. So far, seventy countries have been approved for emergency financing (financial support without need for a program). However, it is not only the lowest income economies that may find their existing fiscal space limiting in the face of this crisis. The IMF has also established a short-term liquidity line for member countries with strong fundamentals and policy frameworks.

At first glance, it might seem like already high fiscal deficits are no impediment to drumming up new fiscal measures to fight this crisis. The IMF estimates Brazil’s fiscal response to the crisis to be worth 11% of GDP, for example, and South Africa’s Treasury estimates its response to be worth 10% of GDP. This is on par with programs in countries like the US and Germany (9% and 13% of GDP, respectively, according to Bruegel estimates). Meanwhile, Brazil and South Africa both had fiscal deficits of at least 6% of GDP in 2019 (IMF estimate). India, in contrast, with a similarly wide fiscal deficit (-7.4% of GDP in 2019) has implemented fiscal measures with an above-the-line impact worth only 1.9% of GDP according to the IMF.

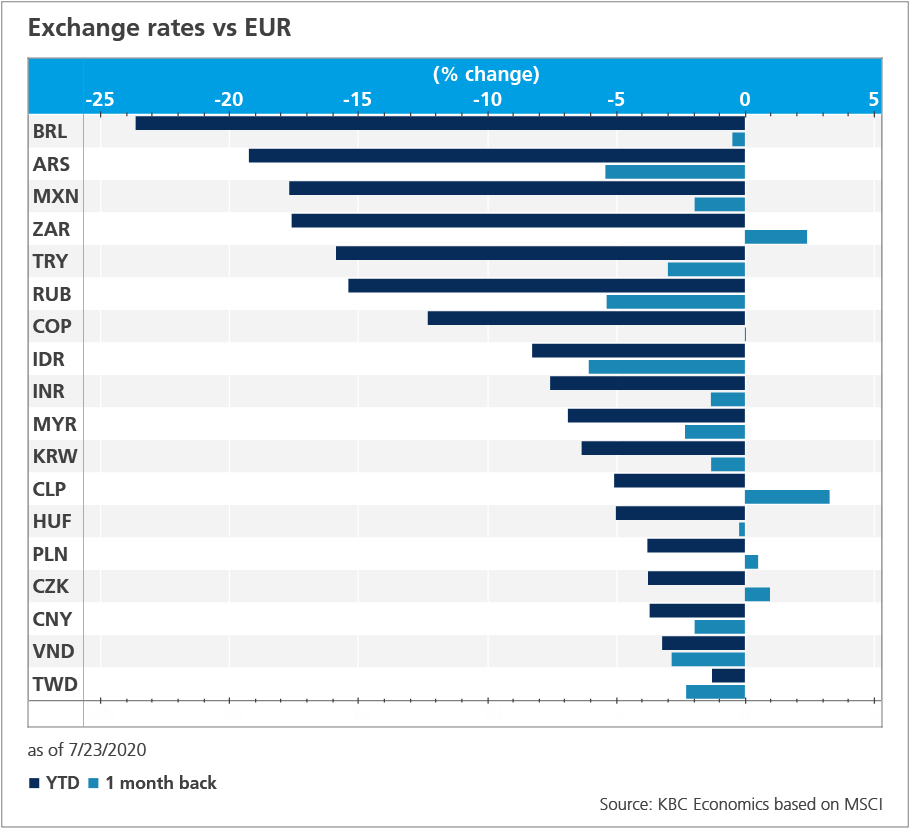

Of course, these necessary expenditures to protect the economy and fight against Covid-19 are not without consequence for economies like Brazil and South Africa. These two countries, after all, have seen their currencies depreciate the most against the USD since the start of the year along side the Argentine peso. And of course, these are countries with twin deficits, i.e. fiscal and current account deficits, adding to their vulnerabilities.

Easy policy gives a boost

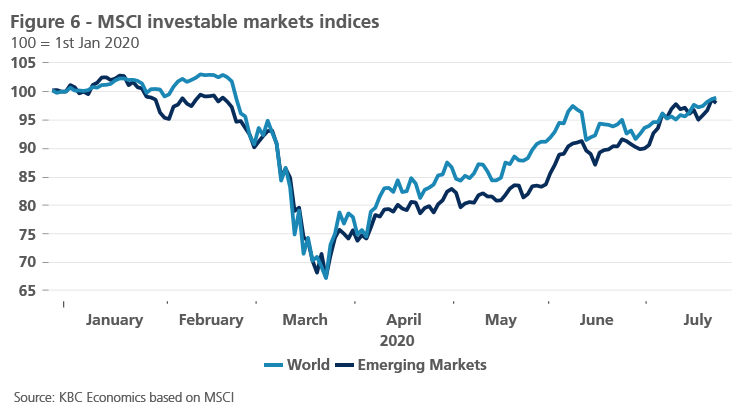

Fortunately, the sudden stop and reversal in capital flows to emerging markets seen earlier this year has ceased, and according to the IIF, portfolio flows in April, May and June were positive. Debt inflows in June, for example, are estimated to be around USD 23.5 billion, while equity flows were around USD 9.5 billion. Indeed, emerging market stock markets have recovered in line with advanced economy equities (figure 6). Emerging market currencies have seen some stabilization and a more limited recovery as well after nearly all depreciated sharply against the USD in March. And despite higher issuance among emerging markets, most have seen their 10-year interest rate differentials versus US government bonds decline since end-March (though they are still generally higher than at the start of the year).

Some of this reversal can be chalked up to improving risk sentiment as economies around the world have started to reopen and recover. However, the substantial steps taken by central banks worldwide to improve liquidity and ease financial conditions cannot be discounted. With policy rates back to the zero-lower bound in the US, for example, and the Fed, ECB and BOJ all restarting or significantly expanding their quantitative easing bond purchases, emerging market debt and equity can offer an attractive return to investors. However, these developments can also lead to longer-term risks, as loose financial conditions often lead to mounting debt and foreign currency liabilities in emerging markets, which can cause stability issues if risk sentiment quickly changes course.

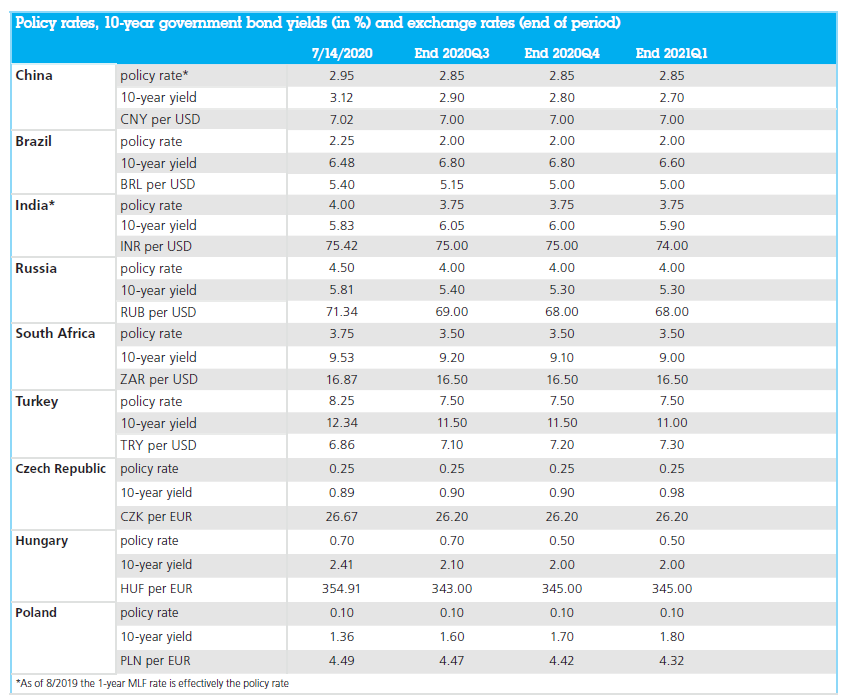

And advanced economy central banks are not the only ones stepping up their policy accommodation. Aside from traditional policy rate cuts, which have been ample, emerging market central banks have even started to dip their toes into the quantitative easing game. And despite previous conventional wisdom, this hasn’t led to a huge spike in interest rates or further steep currency depreciations for these economies. There are several reasons for this. First, the purchase sizes are relatively small compared to that of advanced economies. Second, many emerging markets have developed their domestic capital markets over the years. Third, emerging markets have worked to improve the credibility of their institutions, particularly that of their central banks, and inflation in most of the countries remains anchored and often below target. This experiment in emerging market quantitative easing, however, is not without risk, especially for those countries with high external liabilities (like South Africa and Turkey) and a reliance on foreign investors. Thus, one might say that while advanced economies’ monetary accommodation has attenuated emerging market vulnerabilities for the moment, these vulnerabilities are still present and cannot be completely ignored.

Emerging Asia

China

Relative to the rest of the world, China is the furthest along in its post-Covid recovery, which is to be expected given that China was the first country to implement major economic and social lockdowns and, consequently, the first to lift those measures. Though China experienced a historically sharp contraction in Q1 2020 (-6.8% yoy), growth recovered to 3.2% yoy in Q2. The GDP figures, as well as activity and sentiment data, suggest that China’s recovery is ongoing and that it appears to be ‘V-shaped.’

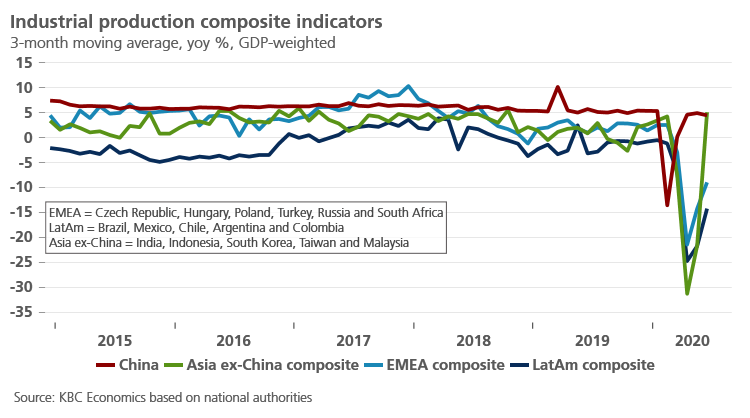

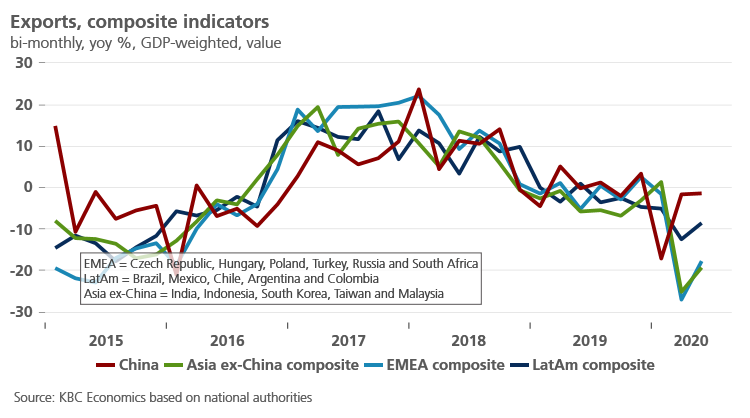

The industrial sector is leading the way with industrial production growth rates of 4.4% and 4.8% yoy in May and June, respectively. The service sector and retail trade, in contrast, is lagging. Retail trade has yet to recover to positive year-over-year territory but has improved from -15.8% yoy in February to -1.8% yoy in June. From a trade perspective, Chinese exports recovered in April (8.2% yoy) following year-over-year contractions in both February and March (-15.9% and -3.5% respectively). Export growth dipped to 1.4% yoy in May but accelerated again to 4.3% yoy in June, perhaps reflecting weaker global demand in May and the expected start to the global recovery in June.

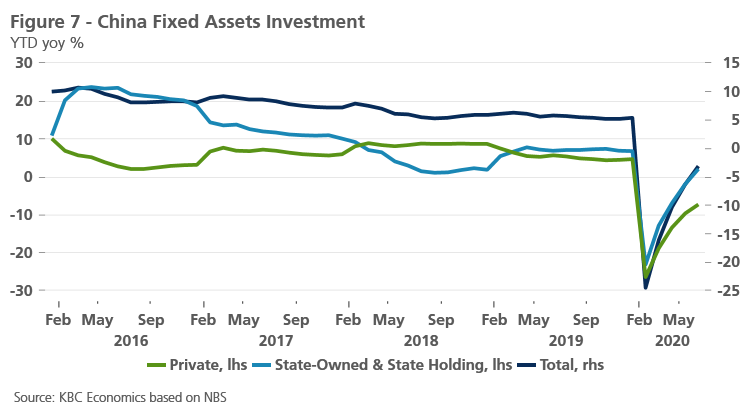

While China’s policy response to the coronavirus crisis has been relatively more muted compared both to other major economies and its previous response to the global financial crisis, policy is likely still playing an important role in China’s recovery. The IMF estimates China’s fiscal policy response at about 4.1% of GDP. However, at the same time, China’s local government bond issuance increased significantly in May. New credit in the form of corporate bonds has also been particularly strong this year, especially through April. Indeed, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have led the rebound in fixed asset investment since February and SOEs are reportedly being relied on again to support employment (figure 7). The rise in corporate credit can likely also be attributed to measures taken by the Chinese central bank (PBoC) to increase lending to corporates and SMEs. Other actions taken by the PBoC to improve liquidity and ease financial conditions in China included reducing the Bank Prime Loan Rate by 30 basis points to 3.85 since the start of the year, cutting the reserve ratio requirement from 13% to 11%, and injecting cash into the market at the beginning of the crisis via open market operations.

And while these policy measures may be supporting the recovery, growing debt burdens and easy financial conditions renew long-held concerns by some market participants and economists that China’s growth model is unsustainable, or that a financial crisis might be brewing under the surface. The outperformance of China’s equity market in recent weeks, in particular after state media came out in support of a “healthy bull market,” has stoked these concerns in the short run. In the longer run, China will likely need to address its overreliance on debt-led growth and state-owned enterprises and continue on its path towards a more service and consumption-oriented economy. Indeed, given already high debt levels among not only the government and corporate sector, but also among households, our long-term view that China’s economic growth will face headwinds during this transition still holds.

At the same time, the fact that the initial coronavirus shock did not cause any major, lasting meltdown in China’s financial sector is a sign that perhaps worries of a bubble are overblown. Indeed, China’s strong state influence over important players in the economy (such as banks and SOEs), its relatively closed financial system, and its ample reserves are all important factors to consider when trying to assess the fragility of China’s economic system. Thus, while it is important to monitor financial sector risks and the future trajectory of China’s debt, we expect the recovery in China to continue and for real GDP growth overall to reach 1.8% yoy in 2020 before recovering to 8.1% in 2021.

India

India has seen rising confirmed Covid-19 cases and death rates per capita since mid-March, despite introducing a relatively strict lockdown starting 24 March. The government began to lift those measures at the end of May, and the growth rate of new cases has clearly accelerated since June. India’s economy therefore likely endured a steep contraction in Q2 and may struggle to find strong footing during the recovery phase starting in Q3.

The fact that India’s fiscal policy response has been relatively muted compared to other larger economies (direct government spending on crisis measures amounts to only around 2% of GDP), may also limit the strength of the recovery. With a government deficit last year estimated at 7.4% of GDP (IMF), India doesn’t have an enormous amount of fiscal space to work with.

The central bank (RBI), however, has stepped in with fairly substantial policy easing. Over 2019, as the Indian economy slowed significantly, the central bank cut the repo rate by 135 basis points to 5.15%. Since March 2020, the RBI cut the policy rate by another 115 basis points to 4%. The RBI also introduced liquidity-injecting open market operations and lending through standing facilities. Indeed, the monetary authorities in India have been working to improve credit in the economy for quite some time, as a credit crunch last year, driven by a crisis in India’s shadow banking industry, contributed to slowing growth in recent quarters.

Year-over-year quarterly growth slowed steadily from 5.7% in Q1 2019 to only 3.1% in Q1 2020. This brought fiscal year 2019 real GDP growth to only 4.2%. And though India did register positive growth in Q1, the brunt of the negative consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic can be expected to show up in the Q2 figures. India’s business sentiment surveys hit their lowest levels in April, with the composite survey falling from 50.6 in March to a dismal 7.2. The composite has recovered somewhat (to 14.8 in May and 37.8 in June), but is still well below the level that signals expansion. On the more positive side, industrial production grew 64.9% mom in May. However, this followed contractions of 54.5% mom in April and 12% mom in March. That leaves industrial production still well below pre-Covid levels. Similarly, unemployment rose to 23% in April and May but declined significantly to 11% in June. The labour market picture is clouded, however, by reports that many migrant workers with little recourse fled cities during the lockdown, resulting in labour shortgages. These points, along with other data like petroleum consumption and consumer confidence, support the view that while the recovery should start from Q3 on in India, it will likely be gradual.

Latin America

Latin America has been hard hit by the pandemic with Brazil, Peru, Chile and Mexico among the top ten countries with the highest number of Covid-19 cases. Case rates grew rapidly from April to June and continue to rise in certain countries in the region, including Argentina, Mexico and Colombia. Brazil, which has the second highest number of confirmed cases worldwide after the US, has seen some hopeful signs of stabilization since the beginning of July.

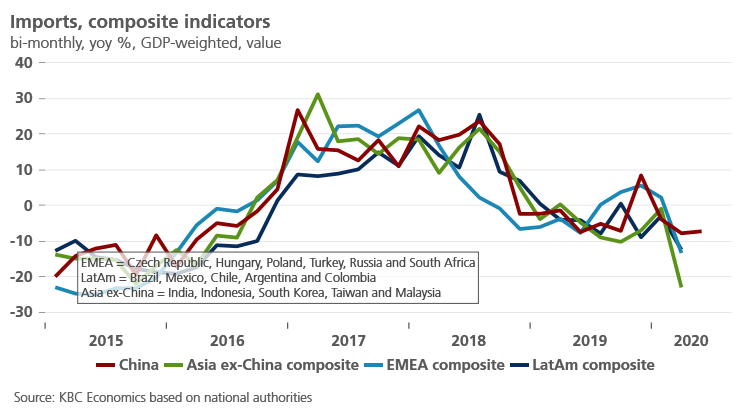

The economic contraction in the region is expected to be very sharp this year. Mexico and Argentina both saw steep contractions in Q1 2020, after already continuing (Argentina) or entering (Mexico) a recession in 2019. Argentina’s economy contracted 5.3% yoy in Q1 and Mexico’s shrank by 2.2% yoy. Brazil’s economy also contracted in the first quarter of the year but only mildly (-0.3% yoy). Consumption and exports both fell in year-over-year terms, while investments and inventories rose. Q2 will be far weaker, with Brazil’s activity tracker contracting sharply in April (-13.3% yoy) and hardly recovering in May (-12.7% yoy). As mentioned previously, Brazil has rolled out a fairly large stimulus package, and the central bank has introduced substantial monetary policy easing (including 220 basis points of rate cuts), which should help the recovery.

However, ongoing concerns about Brazil’s deep fiscal deficit and high public debt burden are only heightened by the new costly, albeit necessary, measures taken to fight the crisis. These concerns could weigh down Brazil’s recovery in the medium-to-long run.

EMEA

Central and Eastern Europe

Most countries in Central and Eastern Europe have managed to bring the Covid-19 pandemic under some level of control for the time being, with new case rates stable and relatively low in Hungary, the Czech Republic and Poland. There were some differences across economies in the region in terms of their relative hit to GDP in the first quarter. Compared to the last quarter of 2019, real GDP was 3.3% lower in the Czech Republic. This contrasts with the relatively mild hit to the Hungarian and Polish economies (both -0.4% qoq).

A large part of the difference was likely driven by the timing of the more drastic lockdown measures, which in particular in the Czech Republic came very early. Looking ahead, there are not many reasons why the Czech economy should significantly underperform the region in the second quarter. The earlier adoption of lockdown measures in the Czech Republic also led to an earlier relaxation. Furthermore, the Czech labour market remains, on the surface, in good shape, with unemployment increasing by only one tenth of a percentage point (to 3.7%). This is a very slight increase given the state of the economy. It can likely be contributed both to Kurzarbeit, the programme through which the state contributes to companies’ personnel expenses, and the positive expectations that companies have for next three months. If the Kurzarbeit programme ends as planned (that is in August), more pronounced dismissals would not be likely until autumn. In general, however, the country is vulnerable given its strong industrial base and reliance on the automotive sector in particular.

Fiscal stimulus support differs across the region, but direct comparisons between countries is difficult, as some forms of support may be more efficient than others. The Czech Republic, for example, has announced a significant fiscal response (more than Hungary or Poland), but much of this comes in the form of guarantees. While guarantees can improve liquidity and support businesses, they require action from impacted companies and can lead to implementation bottlenecks.

For now, the industrial production data point to misery across the region in April and May, with April year-over-year contractions ranging from 27.5% in Poland to 34.5% in the Czech Republic and 38% in Hungary. Though May showed monthly improvements across the board, industrial production still remained well below the previous year’s level. Thus, Q2 can be expected to have been very weak for the region.

Russia

Russia has been one of the world’s worst-hit countries by the Covid-19 pandemic. While the number of new cases peaked in mid-May, the spread of the virus has not been contained (7-day moving average of new cases remains above 6,500), leaving the authorities with a limited room for easing stringent lockdown measures. These have not been implemented before late March, which is the main reason behind marginally positive real GDP growth of 0.3% quarter-on-quarter in the first three months of 2020.

The major hit to economic activity is instead expected in the second quarter which saw a sharp drop in both consumption and investment activity as well as a sluggish export performance, notably due to the tumbling oil prices. The policy response to mitigate the adverse impact from Covid-19 was limited at first, and policymakers have been only gradually shifting up the gears of fiscal and monetary stimulus. Still, compared to emerging market peers, the policy actions are significantly less aggressive. This is, after all, one of the major arguments why we remain relatively conservative in our outlook, expecting the economy to contract by 5.5% in 2020 and to rebound by 2.9% in 2021.

Turkey

Strict lockdown measures took a toll on Turkish economic activity in the first quarter of 2020, though the corona-induced policies have only been implemented since mid-March. Compared to the previous quarter, the Turkish economy saw a growth slowdown from 1.9% qoq to 0.6% qoq. Nonetheless, the major blow to the economic activity materialised in April and May with stringent quarantine measures being gradually lifted from June onwards.

Overall, we project a sharp contraction of 6.5% in 2020 with lockdowns and follow-up income and employment losses weighing on consumption. Likewise, investment is set to decline abruptly due to elevated uncertainty, while high exposure to tourism will be a drag on exports amid weak external demand. The recovery is expected to be gradual with growth picking up by 4.7% in 2021, but ultimately being constrained by generally weak macroeconomic fundamentals.

Although the policy space to mitigate the effects of the corona crisis is limited, the authorities have implemented a series of measures, ranging from rate cuts and a front-loaded QE programme on the monetary policy front, to wage support, tax deferrals and direct cash transfers, together amounting to some 5.5% of GDP on the fiscal front. Also, quasi-fiscal stimulus, namely highly unorthodox measures boosting credit growth have been increasingly used, raising concerns about the sustainability of the recovery path. Finally, the Turkish central bank has seen the fastest pace of foreign reserve depletion across the EM in 2020 due to the continuous FX interventions to defend the lira. This, in our view, increases the risk of the abrupt monetary tightening needed to prevent the repeated crash of the lira.

South Africa

South Africa has seen a spike in its number of confirmed Covid-19 cases only in the past few months. Through March and April, cases remained relatively low, but South Africa’s economy came into the crisis with very weak momentum. First quarter GDP growth contracted 0.5% qoq, following contractions in both Q4 (-0.36% qoq) and Q3 2019 (-0.2% qoq) as well. Q2 however, is likely to show the brunt of the economic fallout, as evidenced by high frequency indicators. The Markit composite business sentiment survey fell from 44.5 in March to 35.1 in April and 32.5 in May. It recovered somewhat in June (42.5) but remains well below expansionary territory. Electricity production dropped sharply too (-22% yoy in March and -14% yoy in April), while manufacturing plummeted 48.5% yoy in April.

Like in Brazil, South Africa has introduced substantial fiscal and monetary stimulus (including government bond purchases by the central bank). However, South Africa (again like Brazil) is also saddled with a twin deficit problem. Though the country has tried for years to consolidate its wide fiscal deficit (-6.3% of GDP in 2019 according to the IMF) very little progress has been made, in large part due to South Africa’s consistently weak growth performance, which in turn can be attributed to a myriad of long-standing structural issues. As such, South Africa’s post-Covid recovery is likely to be relatively more muted, with heightened risks stemming from its external vulnerabilities and public financing.

Tables and Figures