China’s technological ambition in the spotlight

China’s main structural economic goal is to shift from “high-speed growth” to “high-quality growth”. To a large extent, this means focusing on the higher-value-added end of manufacturing, i.e. high-tech exports. China no longer wants to be seen as the factory of the world, but rather as the tech incubator of the world.

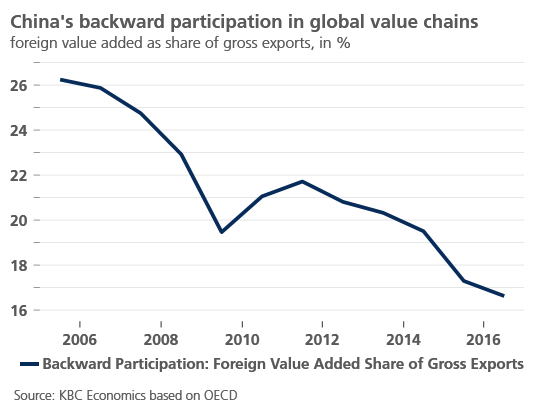

This transition has been underway for some time, with the first leg drawing criticism from the US and EU for China’s alleged intellectual property infringements and forced technology transfers. As figure 1 shows, China’s backward participation in global value chains has dropped substantially since 2005. This means the foreign value added in China’s exports has declined, which is a sign that China is indeed working its way up the value chain.

Now, however, China’s quest for technological might is kicking into a new phase – a new phase that will lead to even more conflict. China is leaving behind the technology model that focuses on imitation and imports. As mentioned in a previous KBC Economic opinion of 24 May 2019, China has made and continues to make substantial investments into research and development. Indeed R&D expenditures as a percentage of GDP now match that of the EU. And the fruits of those investments are becoming clear with, for example, China recently becoming the first country to land a discovery probe on the far side of the moon and with Huawei’s rollout of its 5G network.

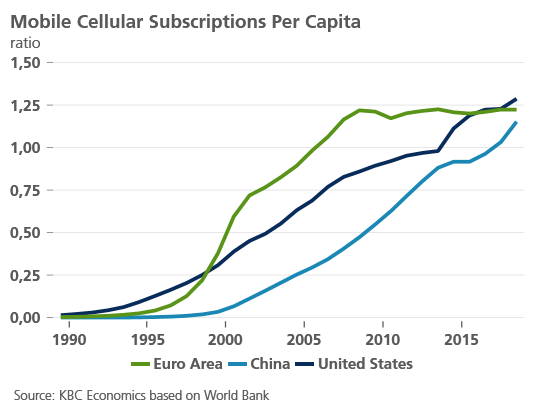

The response from the EU and US to the latter, highlighting security threats and placing Huawei on an effective trade blacklist, is indicative of the higher scrutiny China and Chinese technology companies will face going forward. While this scrutiny may be a headwind to China’s continued economic success, as made clear by the drag from the trade war, China’s technological progress won’t likely be hobbled in the near future. China’s own domestic market is the largest internet market in the world. The ratio of mobile cellphone subscriptions relative to the population is roughly on par with that of the EU and the US according to the World Bank. Furthermore, the skills gap in science and technology is closing. According to a World Economic Forum 2016 report, there were 4.7 million recent STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) graduates in China relative to only 568,000 in the US. Beyond its own market, as the regulatory framework for the tech sectors in the US and Europe grows due to privacy and security concerns, China will benefit from this relative handicap.

Thus, while the US and China may be working towards trade deals that will address some of the issues that led to the trade war and possibly roll back some tariffs, China’s technological prowess will remain in the spotlight, and likely cause further conflicts, in 2020 and beyond.