Economic perspectives November 2019

Read the full publication below or click here to open the PDF.

- Economic indicators in the euro area are showing tentative signs of stabilisation. Euro area real GDP growth stabilised at 0.2% in Q3 but underlying geographical differences persist. Growth figures for some major economies, such as France and Spain, were better than expected. On the contrary, Italian growth remains muted. Most importantly, the German economy reported marginally positive growth in Q3, meaning the largest European economy has narrowly avoided a technical recession. Our scenario for the euro area economy remains unchanged: we expect growth to recover gradually, but stay muted in the short-term.

- The deceleration of the US economy is becoming more pronounced, although a broad-based recession with negative spillovers from manufacturing weaknesses to the services sector is not likely. The US labour market is showing some signs of cooling but the overall performance remains resilient.

- Recent weeks have been characterised by a revived optimism driving movements in equity and bond markets. Positive signals from the US-China trade negotiations as well as a reduced likelihood of a hard Brexit were the main drivers. However, despite these favourable developments, we are not out of the woods yet. Uncertainty will remain key surrounding the US-China trade dispute and the Brexit saga. After all, the US-China partial trade deal and the approval of the UK withdrawal agreement will not be a final end point. These sentiment swings may continue to fuel financial market volatility at the end of 2019.

Euro area: no further deterioration ahead?

The economic outlook for the euro area is gradually becoming less pessimistic. Several indicators signal that the recent economic slowdown in the euro area is coming to a halt. Real GDP growth figures for Q3 2019 indicate that euro area growth stabilized at 0.2% (qoq) with strong growth performance in some economies including France (+0.3% qoq), Spain (+0.4% qoq) and the Netherlands (+0.4% qoq). Also German growth figures for the third quarter positively surprised. Against expectations, Germany reported slightly positive real GDP growth in Q3 (+0.1% qoq), thereby avoiding a technical recession after negative growth in the previous quarter (-0.2% qoq). Besides, also the Central and Eastern European economies reported relatively strong growth figures, albeit with a moderation in growth rates across the region.

Looking forward, business sentiment indicators in most euro area countries have broadly stabilised, though still at very low levels. The overall picture remains broadly similar to previous months, with pronounced weaknesses in the manufacturing sector and some contagion towards services activities, with the latter mainly concentrated in Germany. Importantly, however, recent corporate sentiment indicators don’t signal a further deterioration. Signs of a major turnaround remain absent for now but the stabilisation in sentiment suggests that there will be no further economic worsening either. Hence these indicators seem to suggest that the current dip is of temporary nature.

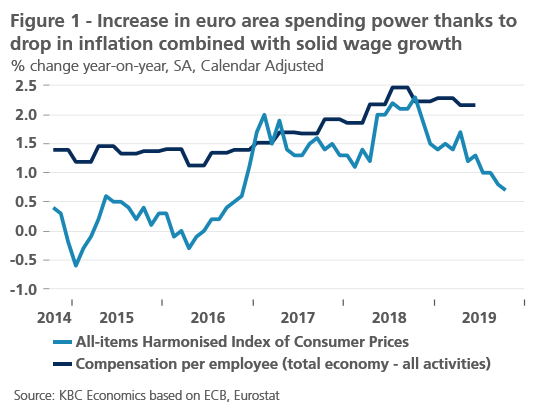

Moreover, high frequency indicators confirm the persistent resilience of consumption demand in the euro area. Consumer sentiment has weakened somewhat in most countries, but nevertheless remains at remarkably solid levels. Furthermore, household expenditures are underpinned by the drop in headline inflation, which decreased further to 0.7% year-on-year in October. The downward trend in euro area inflation in recent months has been caused mainly by negative contributions of the energy price component (-3.2% yoy in October). Meanwhile, core inflation – excluding volatile components such as energy, food, alcohol and tobacco – continues to hover around 1% yoy. Given that nominal wages keep growing at a sound pace, the inflation decrease means a rise in spending power for consumers (figure 1). Furthermore, employment growth, although showing signs of weakening in some countries, remains supportive for private consumption. The slight increase in the households savings rate suggests that in case economic conditions deteriorate, there is still some buffer to consumption.

From the fiscal policy side, support - albeit moderate - for economic growth seems to be on the way in the coming years. Based on the draft budget proposals the euro area countries submitted to the European Commission and looking at the main euro area economies, Germany, the Netherlands and Italy plan for a mildly expansionary fiscal policy. Expressed as a percentage of their potential GDP, the reported change in the cyclically adjusted primary budget balance in 2020 compared to 2019 amounts to respectively -0.75%, -1.10% and -0.30% (negative sign meaning budgetary expansion). However, on current plans, fiscal policy is unlikely to dramatically boost euro area activity in the near term. Recent ECB calls for a more supportive fiscal policy stance may signal an increasing focus on the role of government spending in the European economy. However, it remains to be seen whether this emerging discussion will prompt considered interventions that will enhance productive and broader socio-economic capacity or simply lead to poorer trends in the public finances.

All in all, recent data confirm our scenario. Economic activity in the short term will remain rather subdued without a sharp or immediate rebound, but the downward trend in sentiment seems to have paused. The latter suggests that the euro area is not heading towards a deep, broad-based recession. Hence, our growth forecasts for the euro are unchanged. We project annual average real GDP growth to reach 1.1% in 2019 and 1.0% in 2020. We expect underlying quarterly dynamics to show a gradual recovery from 2020 on. Note that some international institutions, notably the IMF, are more optimistic and expect a more substantial economic recovery in 2020 for the euro area economy (1.4%). However, neither sentiment indicators nor structural dynamics convincingly support this optimism in our view.

German signals less negative

After months of disappointing activity reports and growing pessimism among corporates, most recent data cautiously signal that the end of the German economic downswing is likely near. This is evident in the soft but positive and clearly stronger than expected marginal gain in GDP for the third quarter. It is also consistent with other recent developments. In line with the stabilisation of global trade volumes, German export and industrial production data are no longer showing a further deterioration. Business sentiment indicators have been showing a more mixed picture, with messages from the national IFO indicator less pessimistic than from the PMI. Nevertheless, the manufacturing sector is the weakest link according to both indices. The main stronghold in the German economy remains private consumption. Consumer confidence has weakened, but remains at relatively high levels. Retail sales growth has strengthened again in recent months and, as a result, consumer spending supported the better than expected outturn for Q3 2019 GDP. Labour market trends, despite some early signs of unemployment picking up again in Germany, remain supportive for consumption going forward.

Overall, we expect German quarterly GDP growth to gradually recover in the quarters to come. Nevertheless, given the weak growth performance thus far in 2019, annual growth rates for this and next year are projected to be subdued and substantially below Germany’s growth potential.

US deceleration, not a recession

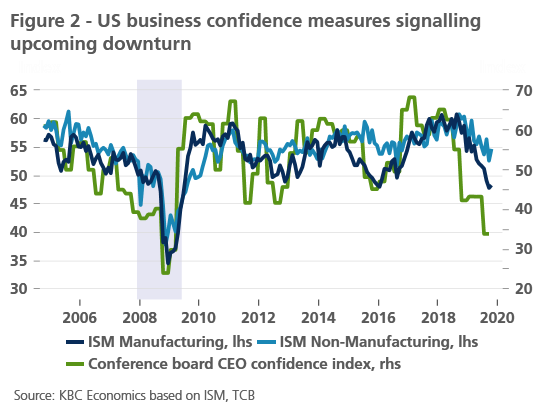

The US economy continues to perform strongly, though at a slower growth pace. The advance real GDP growth estimate for Q3 2019 was broadly in line with the KBC estimate (1.9% qoq annualised versus 1.8% expected). The slight deceleration in real GDP growth compared to the previous quarter reflected decelerations in personal consumption expenditures and government spending and a larger decrease in non-residential fixed investment. Net exports contributed slightly negatively to growth. Based on early indicators for Q4, the business situation looks somewhat more gloomy. Confidence measures are downbeat with the ISM manufacturing remaining in contraction territory at 48.3 (albeit up from September’s reading of 47.8) and CEO confidence index is at its lowest level since Q1 2009 (figure 2). This has been mirrored in the downward trend in industrial production, which decreased in September (-0.2% yoy) for the first time since 2016.

Nevertheless and more importantly, the services sector – which represents the vast majority of economic activity – is holding up relatively well (figure 2). The ISM non-manufacturing index jumped to 54.7 in October, thereby easing concerns about negative spill-overs from the export-oriented manufacturing industry towards the domestic services sector. Important sub-indices, such as business activity, employment and new orders also increased, suggesting that there will be no immediate relapse in November.

Meanwhile, the US labour market is showing some signs of cooling. Though national job growth remained solid in October (+148k), state-level data indicate a more mixed picture. Though still a small minority, there has been some uptick in the number of states reporting job losses. (see Box 1)

Overall, this is in line with our scenario of gradually decreasing US growth dynamics without a severe recession. Our US growth forecasts hence remain the same as last month. The 2019 annual average real GDP growth is expected to reach 2.3% and 1.7% in 2020. Private consumption will remain the main growth contributor going forward.

Box 1 - US labour market showing signs of cooling down

The health of the US labour market is closely monitored by many economists. The fact that the American consumer is the backbone of the economy at least partly explains why. The positive news is that the monthly labour market report is still solid. In October 2019, 128,000 new jobs were created. That was considerably more than expected (85,000). Markets feared that the strike at the car giant General Motors would have a greater impact on the figure for October as striking people are not taking into account in the employment figures. In addition, job creation for the months of August and September was adjusted upwards by a strong 95,000. In October, the participation rate rose to 63.3% as more people either found work or began searching for a job. The unemployment rate increased marginally from 3.5% to 3.6% in October. From a long-term perspective, however, it remains very low. Wage growth was 3% year-on-year in October, which was more than sufficient to support real purchasing power.

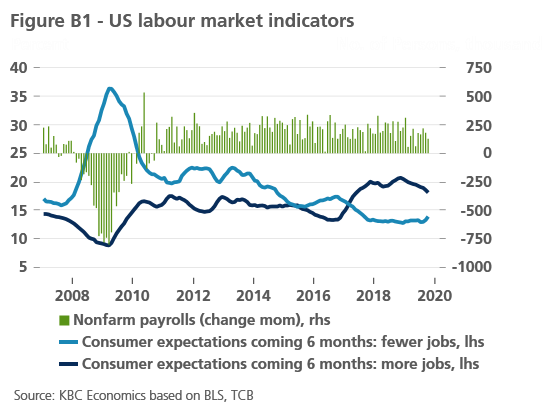

However, the sky above the American labour market is not entirely free of (dark) clouds. One statistic that we will follow up further comes from the Conference Board Consumer Confidence survey. This is a monthly survey of American consumer confidence. In doing so, it emphasises the employment situation and is therefore closely linked to the ‘payrolls’. The survey shows that the average consumer is becoming more gloomy about the future. A steadily decreasing number of respondents think that more jobs will be available over a period of six months (figure B1). On the other hand, the proportion that thinks that there will be fewer jobs over the same period of time is cautiously increasing. However, we don’t think the US labour market is on the brink of a crash. Moreover, it is too early to talk about a change in sustainable trends. However, we will keep an eye on the further evolution of this data in the coming months.

The return of market optimism

Equity and bond market movements are indicative of increased optimism in recent weeks reflecting positive signals coming from several sides. Recent developments in relation to the main risks to the global economy i.e. Brexit and the US-China trade war have supported this optimism.

Worries about the possibility of the United Kingdom exiting the European Union without any sort of deal have decreased now that the UK government and the European Commission agreed on a revised withdrawal agreement as well as on an extended deadline for the approval of this agreement by the British and European parliaments. It is now envisaged that the UK will leave the EU by the end of January 2020, or earlier if the withdrawal agreement gets approved by the British parliament sooner. However, that withdrawal agreement also envisages a transition period out to the end of 2020 during which the UK’s current relationship with the EU would be effectively unchanged. On 12 December general elections will be held in the UK. Based on recent polls, Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party is likely to strengthen its position – although opinion polls have given several seriously misleading signals in recent years. Hence, an approval of the withdrawal agreement in British Parliament before 31 January 2020 seems feasible and likely. Attention will then shift to what is likely to be a difficult task of negotiating a full trade agreement between the UK and EU before the end of next year but, for now, markets are understandably focussed on the much reduced threat of a disorderly Brexit.

Positive news also came from the US-China negotiation table in recent weeks. Negotiations appear to be going in the right direction and it now looks likely that a partial trade deal will be reached within a relatively short period of time. This ‘light’ trade deal could provide some temporary relief and is likely to cause a pickup in business sentiment in the short term once the deal is signed.

Financial markets reacted positively to these favourable developments in risk factors and the slightly better economic data. Both German and US long-term government bond yields increased significantly and are now almost fully recovered from their sharp drop during the summer months. Equity markets also flared up and the recent strengthening of some currencies (e.g. EUR versus USD, HUF and CZK versus EUR) illustrated the risk-on mode in markets. The recent upticks in long-term bond yield led us to revise our year-end forecasts for both the US and German bond yield towards 1.80% (from 1.60%) and -0.40% (from -0.70%) respectively. Hence, although we acknowledge that the recovery of long-term bond yields from that deepest levels is structural, we remain cautious about the future evolutions in long-term yields. Markets not only overreacted on the downside, but they are likely to overreact at this moment on the upside too, neglecting many risks that still surround the US-China trade war, Brexit and other international developments.

Uncertainty remains key

Although recent signals have been more positive than news flows over the past year, we want to stress that there are still difficult times ahead with likely lots of remaining uncertainties. In the case of Brexit, the withdrawal agreement is far from complete (see also: KBC Economic Opinion of 31/10/2019). The withdrawal agreement is only a temporary arrangement to avoid the UK crashing out of the EU and causing major economic damage. The future long-term relationship between the UK and the EU is vaguely outlined in an accompanying political declaration. It remains to be seen how that document’s good intentions will translate into a detailed trade agreement between the UK and the EU27, as well as broader agreements on investments, regulatory cooperation, migration and labour mobility rights. The current deadline to reach a comprehensive UK-EU trade deal is set at the end of 2020. Given the complexity of matters, this is highly unlikely to be met. The turbulence leading up to the deadline is expected to cause a temporary drop in the German bond yield again towards end 2020. Hence, the Brexit ‘cloud’ will continue to darken the UK and European growth outlook going forward. Therefore, we keep our forecasts for end 2020 for the German 10-year bond yield unchanged at -0.30%, reflecting the expected uncertainty and possibly turbulence at the time the UK and the EU27 have to reach a final agreement on their future economic relationship.

In the case of the US-China conflict, we’re not out of the woods yet. Aside from providing some short-term relief, the partial trade deal will most likely lack significant concessions and have no marked positive impact on growth. The structural issues – such as the lack of a credible Chinese enforcement system to police intellectual property rights and the US demand to reduce Chinese state involvement in industrial policies – are likely to remain unresolved. Also the battle for global technological and therefore economic leadership is unlikely to be ended (see also: KBC Economic Opinion of 24/05/2019 ). The further de-escalation in US-China trade war will hence have a limited effective economic impact as the structural political-economic conflict will continue to weigh on sentiment and growth.

Besides these risk factors, other elements remain on our risk radar as well. The protests in Hong Kong have been ongoing for quite some time now and are clearly impacting economic activity in China. Troubles remain relatively contained until now, but some wider spillovers cannot be fully excluded. For more detailed info, read Box 2.

Box 2 - It’s not only Hong Kong’s economy at risk

The protests in Hong Kong continue with no end in sight. Though the extradition bill that sparked the protests was formally withdrawn in September, the protestors have four other demands, including universal suffrage for electing Hong Kong’s legislative Council and the Chief Executive.

While the protests may be political in nature, they have economic consequences. Already facing slowing growth in 2019 as a result of the US-China trade war and the slowdown in China, activity indicators in Hong Kong suggest that the protests are sharply weighing on the economy. The City University of Hong Kong Consumer Confidence Index, for example, has dropped sharply from 78 in April to 53 in September. The composite PMI also fell from 48.4 in April to 39.3 in October. Retail sales have sharply deteriorated too, contracting 18% yoy in September. Another area where the protests are clearly having a negative impact on the economy is in tourism flows. Tourist expenditure amounted to almost 10% of Hong Kong’s GDP in 2018, 78% of which came from mainland China. In August and September this year, total tourist arrivals were down relative to a year earlier by 39% and 34%, respectively.

But Hong Kong’s economy isn’t the only economy at risk. Hong Kong is an important global financial hub, particularly for mainland China. Precisely because of Hong Kong’s independent legal system, many international investors prefer to invest in China via Hong Kong. Over 65% of foreign direct investment (FDI) into China, for example, is channelled through Hong Kong. Furthermore, a large share of Chinese companies’ Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) and bond issuances happen in Hong Kong. China has also used Hong Kong’s status as a top financial hub to reap some of the benefits of a more open financial sector while also keeping its financial system isolated with strict capital controls. Bond Connect and Stock Connect, for example, allow for equity and bond trading between mainland China and the rest of the world through Hong Kong’s financial infrastructure and institutions. China also channels the majority of its outward FDI, such as for its Belt and Road Initiative, through Hong Kong.

Furthermore, Hong Kong has also helped with China’s goal of internationalising the Chinese currency. According to the BIS, average daily CNY turnover in Hong Kong is almost twice as high as in any of the other top global financial centres (figure B2.1).

Given this close financial connection, the banking sectors of mainland China and Hong Kong are also significantly intertwined. According to data from the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, Hong Kong banking claims vis-à-vis mainland China are roughly 60% of GDP, while liabilities vis-à-vis the mainland are roughly 40% of GDP (figure B2.2). As a result, any long-lasting damage to Hong Kong’s reputation as a preeminent global financial centre can have important ramifications for China.

All historical quotes/prices, statistics and charts are up-to-date until 8 November 2019, unless stated otherwise. The views and forecasts provided are those of 8 November 2019.